Folk music has traditionally been the commoner’s music, with the individual having full control over its composition. Whether fusing rock ‘n’ roll with American folk like The Byrds or blending soulful orchestrations into folk like Bon Iver, the ability of innovative artists to meld musical influences into American folk music is tremendous.

The origins of modern American folk music can be traced back to the 1940s with Woody Guthrie and later with Pete Seeger, who helped popularize folk music. Today, artists like Bob Dylan easily stand out as carrying on the legacy of American folk. In the 1960s, Beatlemania and the rest of the British Invasion had a stranglehold on popular music.

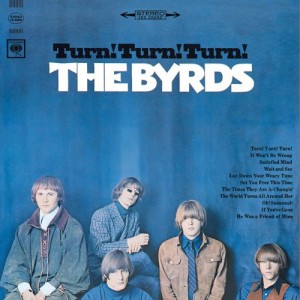

When The Byrds formed in 1964, Gene Clark, David Crosby and Roger McGuinn had all previously been in folk bands, and began by playing covers of Beatles songs with folk overtones. This melding of American folk music and the rock ‘n’ roll sounds of the British Invasion led to The Byrd’s big break: a rock inspired cover of Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man.” As the band took shape, they began using instruments inspired by the Beatles to create a similar rock ‘n’ roll sound.

The result was chart shattering. Suddenly, this group of Los Angeles folk singers had risen to the same level as the Beatles and The Beach Boys. Their popularity was derived from the homeliness of a folk song with the twelve-string electric guitar and beating drums of rock ‘n’ roll. It was this against-the-grain attitude behind The Byrds that led them to unify the folk rock sound and pioneer the genre from the ’60s onwards.

As The Byrds brought rock ‘n’ roll instruments into American folk music, Bon Iver has brought the use of classical instruments into its folk music. An experiment that began in Los Angeles with The Byrds’ pioneering of folk rock, has now evolved into new possibilities for artists such as Bon Iver to bring other musical stylings into American folk music, demonstrating the genre’s increased plasticity.

While folk rock continues strongly to this day with bands like Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros, Good Old War and Fleet Foxes, American folk music continues to find other ways of expressing itself in popular music. Justin Vernon, founder of Bon Iver, has developed his own soulfully orchestrated folk music, using symphonic instrumentation often not found in folk. His approach has proven quite innovative and he has been celebrated for his achievements.

Before I proceed further, may I just say that I feel it to be a sin to have to dissect the folk sound of Bon Iver. Experiencing the music should be a celebration where you and your five closest friends sit in a circle with only incense candles for light as you listen to “Bon Iver, Bon Iver” on 33 1/3 vinyl.

At the core of a Bon Iver song stands, stripped from every other instrument, a folk-sounding acoustic guitar. To create the innovative sound they are known for, Bon Iver crowds the track with numerous delicate orchestral instruments, from pianos and bells, to woodwinds and horns. In “Holocene” the sounds of muted trumpet and vibraphone, isolated, would sound lost and dry. But instead, each sound is orchestrated with perfect cohesion, and thus, Bon Iver has a Grammy nominated song. Each instrument, from the trumpet to the steel guitar, is composed so astutely that the blending sound is often ethereal. It is this composition that makes Bon Iver’s blend of soulfully orchestrated folk music truly innovative.

Bon Iver has popularized soulful modern folk with their instrumentation as well as their vocal techniques and rhythmic properties. Vernon’s voice is characterized by tortured falsettos and bright harmonies dubbed over one another.

Each song is rhythmically rich, from vocals to instrumentation. A Bon Iver song can have ten instruments playing at any given time and yet the music seemingly flows with an atmospheric sense of melodies even without any sort of tempo.

From the lush and legato sounds of Bon Iver to the folk rock of The Byrds, the plasticity of folk music is powerfully demonstrated. Folk music in America continues to define the culture of the commoner, the lyrics of the working family and the influences of our generations.

Email Hornbostel at bhornbostel@media.ucla.edu.