The scorching sun beat down on his shoulders.

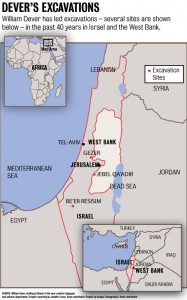

Despite the heat, William Dever kept digging and digging in the hard, dry dirt, at an excavation site in Be’er Resisim, a hilltop site in Israel – alongside 50 of his students.

“We were in the middle of the desert, we lived in tentative camps, hauled water, and nearly starved to death. It was like being on the moon,” said Dever, a new visiting professor in the Near Eastern languages and cultures department at UCLA. “It was an adventure to survive.”

Now, nearly 30 years later, Dever plans to incorporate his memories from this excavation, and others he has taken part in over the course of his 40-year career, into the undergraduate and graduate Near Eastern courses he is teaching at UCLA this quarter.

“Instruction is based on my experience,” Dever said. “I knew (some of) the scholars the students read in their books personally.”

The undergraduate course is “Archaeology of Ancient Israel” and the graduate course is “Seminar: Ancient Syria/Palestine.” He said he intends to put his research on hold so he can focus his attention on the students.

This quarter, Dever is temporarily filling in for Aaron Burke, a professor in the Near Eastern languages and cultures department, while Burke is on leave.

Dever aims to bring real-life experience to his teaching, along with his academic expertise. After earning his doctorate at Harvard University, Dever taught at multiple universities around the world, including the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the universities of Brandeis and Michigan.

He has authored about 30 books and roughly 400 academic articles, he said.

William Schniedewind, chair of the Near Eastern languages and cultures department at UCLA, said Dever will bring an interesting perspective to his classes because his years of research has made him a leading expert in his field.

Schniedewind, also a professor of biblical studies and Northwest Semitic languages, said he first heard of Dever when Schniedewind was a student at Brandeis University 20 years ago and started reading Dever’s work in his classes. The two met 15 years ago when Dever invited Schniedewind to lecture at the University of Arizona.

Schniedewind said his favorite memory with Dever was when he visited him at the University of Arizona – where Dever taught for 20 years.

“He took me for a ride in his 1969 MG sportscar, and let me tell you, it was a wild ride,” Schniedewind said. “Just being with him as he drove his antique sportscar reflected his personality – both the past and the adventure.”

Zach Margulies, a second-year graduate student of Near Eastern languages and cultures, said he has taken the class before but enrolled in it again this quarter since Dever was teaching.

“Professor Dever is a dynamic and a really interesting teacher,” said Margulies, who attended his first day of class with Dever on Tuesday. “He has been in the field since the beginning.”

Sitting in a conference room in the Humanities building, Dever carefully handled some of the artifacts he has collected throughout the years, explaining the significance of each one. As he held a small clay bowl, he said people used the bowl to make yogurt -– about 4,000 years ago.

Dever said while big archaeological finds are important, he has found more satisfaction in being able to weave his research together over time.

“Most archaeologists never make headline discoveries. It is about the accumulation of details,” he said. “It is out of these little bits and pieces that we fit together the picture like a jigsaw puzzle.”

Email Crane at jcrane@media.ucla.edu.

“Click for full size map” doesn’t work on these pictures