Business-minded scouts and rigid American visa policies stunt the growth of Cameroonian basketball and shatter destitute players’ dreams

[dmalbum path=”/images/dm-albums/155out_o/”/]

Since 1919

Business-minded scouts and rigid American visa policies stunt the growth of Cameroonian basketball and shatter destitute players’ dreams

[dmalbum path=”/images/dm-albums/155out_o/”/]

A fan of the senior FAR Compet team shows his support during the Cameroon Cup Finals on July 18.

Correction: The original version of this article published Oct. 11 should have read: “But many Cameroonians say the only way to get an I-20 in Cameroon is to buy it. And sources say the only person in the ‘business’ of selling I-20s is a man named Joseph Touomou.”

Clarification: The Daily Bruin made several requests to Joseph Touomou for a list of players who he said did not pay him for scholarships. Touomou did not fulfill the request.

YAOUNDÉ, Cameroon ““ Fans go crazy when a talented student-athlete from an unknown place takes a college campus by storm.

But what happens to international student-athletes before they reach a Division I university remains largely invisible to even the most die-hard college sports fans across the nation.

The Daily Bruin conducted 31 days of reporting in Yaoundé, Cameroon, and discovered a web of problems that simultaneously stunt the development of basketball in the country and prevent young athletes from achieving their dreams.

Cameroonian basketball players seldom touch a ball before their teenage years and may never be able to afford a pair of proper shoes. The limited court space in the city costs money to rent, and parents often discourage recreational activities in favor of studying.

Even those players who do join a club team lack the proper coaching to develop their game.

And even the most talented players who find a way to succeed usually wind up stuck at a dead end.

Basketball doesn’t pay in Cameroon, players get injured, and if they don’t leave the country, the years pass them by.

The only way to escape and avoid such fate is to obtain an I-20 student visa application. These applications are the golden tickets that come attached to thousands of dollars in scholarship money that pays for an elite education, room and board at private American high schools.

But many Cameroonians say the only way to get an I-20 in Cameroon is to buy it.

And sources say the only person in the “business” of selling I-20s is a man named Joseph Touomou.

“It is a very good business,” said one coach, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution. “Everyone knows. All people talk about it. … The problem is that it seems like there is one way to go to the United States. The way is Joe, only Joe. He has … a monopoly.”

Touomou is one of the first Cameroonian basketball players to ever be successful playing in America. After attending Georgetown in the mid ’90s, he moved on to scout for the Indiana Pacers and later became the coach of the Cameroonian men’s and women’s national teams.

As a result of his success, he has formed scouting relationships with American high school and college coaches, including UCLA men’s basketball assistant coach Scott Garson. He also maintains positive relationships with numerous basketball administrators in Cameroon, including his former teammate Samuel Nduku, the current president of the Cameroonian Basketball Federation.

Administrators such as Nduku praise Touomou’s contributions to basketball in Cameroon, but many players and coaches in the basketball community disdain him.

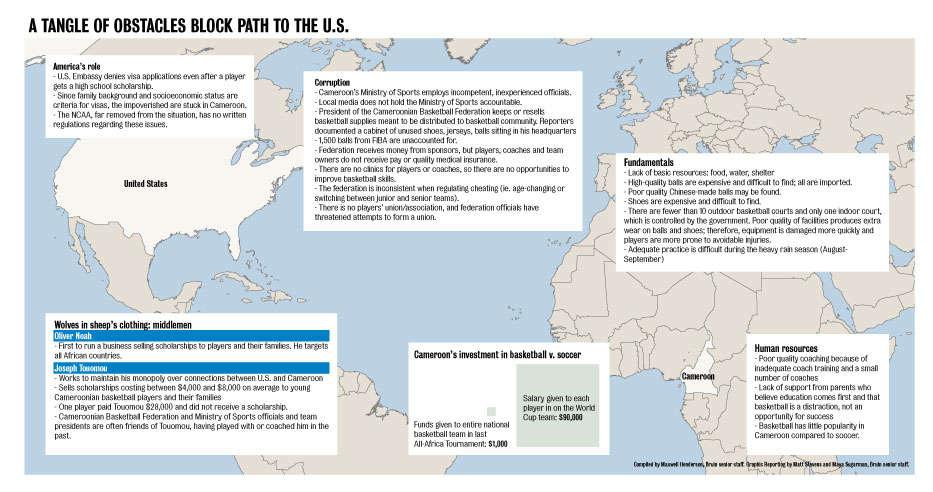

According to numerous sources who know of or have dealt with Touomou, the scout charges around 2 million Communauté financière de l’Afrique (approximately $4,000) for a scholarship.

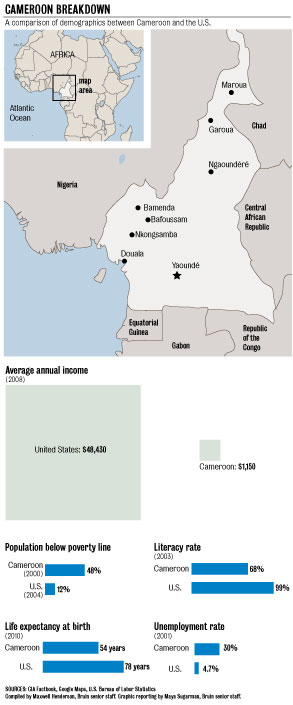

Average yearly income in Cameroon as of 2008 totals $1,150, causing most families to choose between major debts or denying their child an important opportunity for educational and economic advancement.

However, Touomou is not the first person to establish a business selling scholarships. Rather, he is just one of many “middlemen” who scour the African continent for talent and sell I-20s to players with the most promise ““ and the most money. Oliver Noah is one such middleman who began selling scholarships in Cameroon before Touomou but has since branched his services out across Africa, according to sources.

One source estimated that overall, 80 percent of all Cameroonian players who receive a scholarship to the United States paid for it.

But sources also say Touomou is known for giving a small handful of very talented kids free scholarships in order to maintain his reputation as a good scout.

For those outside the talented few, the cost of a scholarship from Touomou can in fact range as high as 14 million CFA (approximately $28,000) ““ money one player said Touomou “swindled” out of his family for two potential scholarships that never came to fruition.

“The worst is that he led me on,” said the player, who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retribution. “He knew that I wasn’t going to travel, that I wouldn’t get out of my club (team) or my situation. It’s really ugly what he’s done.”

Jean Claude Ntep used to run a basketball camp for Touomou but stopped in 2006 after his colleague told him about the business Touomou was running behind the scenes.

“I know, I’m for sure, that so many parents have tried (to purchase scholarships from Touomou),” Ntep said. “There are many of them … with stories that paid 3 million (CFA, or about $6,000) for the I-20.”

Touomou called the allegations, “Absolutely, absolutely, absolutely false” and offered the Daily Bruin “whatever amount of money” to reveal sources.

He added that he would not jeopardize his relationship with good schools for $2,000.

“I call it the sabotage,” he said. “(The sabotage) goes way back to when I played. You have to understand that when I came to the U.S., a lot of people … envied me in Cameroon. … In our culture, people take it too personal. Every game is a war and a fight.

“And I don’t want to start pointing fingers, but people have (charged money).”

Nduku supported Touomou, saying he does not believe the “rumors.”

“I am the lead official, (and) no child has come to prove to me (about Touomou),” Nduku said. “People say things. That’s the general atmosphere in Cameroon. There is too much hearsay and I don’t want to deal with hearsay. I don’t want to destroy someone’s reputation without having any type of proof.”

The Daily Bruin made several requests to Touomou for a list of players who he said did not pay him for scholarships. Touomou did not fulfill the request.

When told of the allegations made against Touomou, UCLA coach Garson said he was unaware that Touomou charged money and that the knowledge would not affect his relationship with the scout.

“It’s no different than I’d work with anyone else (in recruiting),” Garson said. “I don’t know why I wouldn’t talk to him. If Joe calls me, I have no problem talking to Joe and speaking to Joe. He’s been nothing but nice to me.”

The Daily Bruin conducted a thorough review of regulations posted by the NCAA Eligibility Center and Bylaw Article 13 on NCAA recruiting rules and found no information pertaining to middlemen or scouts performing similar business practices.

A spokesperson from the NCAA declined to comment on the situation.

The Cameroonian coach is one of many sources who said he was unfamiliar with the NCAA and its rules. But he added that players know it is unethical to pay Touomou, and coaches discourage them from doing so.

In the end, however, players are left with little other choice.

“Every time, even if you are strong and you are a good player, but you don’t have the money, you don’t get a scholarship,” said Tedd Ray Bitsegui Ambassa, a former national-team standout in Cameroon. “That is a big problem.”

If a player manages to obtain an I-20 student visa application from a school, there remains one additional obstacle between him and an airplane.

The application process to obtain a visa to leave the country has about a 60 percent issuance rate, said Steven Royster, the chief of consular services at the American embassy in Yaoundé.

With an application fee of 70,000 CFA (approximately $140) ““ equally comparable to that of European nations ““ applying for a visa remains a costly risk to take for a Cameroonian.

According to Royster, the criteria for getting a student visa involves meeting three stipulations: A player must establish that he is coming to the U.S. with a purpose allowed within the law, that he is coming for a short period of time and that he will return home after that short period has expired.

“The burden (of proof) is on them,” Royster said. “It’s difficult to establish intent to return.”

One former player, who requested anonymity out of concern that the embassy would deny him a visa in the future, is one of several players who had a high school scholarship available to him in the United States but was denied a visa on several occasions.

The player took three trips to the embassy, paid the fee three times with loans from his siblings, and was denied each time for reasons he said he does not understand. After a third failed attempt, he gave up on his dreams of basketball in the United States.

“They give you a paper and try to explain why ”“ but there is no reason,” the player said. “Because when you are scared, they can see it. … It’s not really objective.”

Royster said embassy officials examine an applicant’s “complete package” which includes academics, sincerity of interest and a family’s social standing.

“They have to have proper foundations here (in Cameroon),” he added when asked to clarify the meaning of the third criteria. “Are they well established in the family unit here? Is it one they will come back to?”

UCLA basketball alumnus and current NBA player Luc Richard Mbah a Moute called it “a tough situation” ““ one that is further complicated by a Cameroonian history of fake paperwork. Many within the country know that in the past, players would commonly falsify their ages in their official documents to appear younger than they really were.

According to Mbah a Moute, a Cameroonian coach compiled a list of 20 to 30 players who he claimed had fake documents and submitted the list to the American embassy just prior to passing away six years ago.

“That changed the whole perspective of the embassy and the policies,” Mbah a Moute said. “They never tell you ““ but I think that changed a lot.”

Royster declined comment when asked about fake documents influencing embassy visa decisions at present. But Ntep, like Mbah a Moute, acknowledged that lying about age used to be commonplace.

“The people from the embassy, they’ve got to be careful,” he said. “Oh, it is very difficult now. Because maybe it is really dirty. Maybe (embassy officials) know more than we think they know.”

Regardless, current players grow more and more frustrated each day as they continue to hear stories of friends and teammates who have been denied visas and now suffer from debt.

At some point, most young men simply give up.

“I don’t have the motivation to continue to try,” said the player who was denied three times. “I am just really tired.”