UCLA is an institution with many moving parts. Something that goes under the radar, though: its side business ventures that don’t directly relate to its educational mission. In this series, staff columnist Mariah Furtek looks at how the blue-and-gold laden university’s often questionable cash grabs affect the campus and local community.

Think of the University of California like a factory of which the two main products are educated students and research. All factories aim to minimize production costs in order to maximize their profitability.

For UCLA, that means exploiting student labor.

Student workers form the backbone of teaching and research. And their work brings in a lot of money – money they’ll never personally benefit from.

The work graduate student workers do as teaching assistants allows UCLA to rake in exorbitant nonresident tuition by expanding the number of discussion sections as class sizes swell.

And the contributions student workers make in laboratories help the university generate the breakthroughs it has made its name on.

All the while, the UC avoids providing student workers fair benefits and protections by officially limiting the hours they are expected to work.

Despite student worker unionizations and lobbying attempts, administrators are adamant: Students are students – no matter how much of the University’s work they do.

Deceiving appearances

American employment is built on the notion that workers will be supported by their government and employer in exchange for the years of labor they provide.

Most pay Social Security and Medicare taxes on their wages, which contribute to future retirement savings. Employers then match these contributions to help fund this basic safety net.

But these taxes are not assessed on student workers so long as education, not employment, is their primary duty.

To take advantage of this tax loophole, the UC ensures student workers appear to be students first and employees second. Namely, it officially maintains graduate student workers at less than half-time appointments while requiring they enroll in 12 units. Emphasizing the education student workers receive allows the University to downplay their employment and avoid offering full protections and benefits.

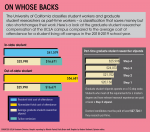

This means significant savings – especially for a university like UCLA, which employs a whopping 16,500 student workers.

And the university is eager to capitalize on these savings.

The Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center terminated its contract with valet service workers in 2017, replacing them with full-time, part-time and student positions that have been insourced.

This happens on campus too. In 2016, a student activist shed light on the pay disparity student employees experience with UCLA Dining Services. The department was offering initial hourly wages of $10.50 to student workers, far below the $16.32 starting hourly wage for full-time employees, despite both doing the same job.

UCLA doesn’t have any hesitation using graduate student workers in the same way.

Most of the responsibility for teaching students falls on graduate student workers. After all, teaching assistants grade exams and papers, lead sections, attend lectures and hold office hours. They’re often the first point of contact for students who don’t feel comfortable approaching professors.

Alex Diones, a doctoral candidate in the political science department, said the lack of Social Security and Medicare contributions is another example of how the university fails to support its student workers.

“Student workers are definitely taken advantage of,” Diones said. “We are not being paid nearly enough for the work we do at this university.”

Without defined contributions to Social Security and Medicare, student workers are less able to build long-term savings, which are especially critical in today’s competitive job market.

“Now, very few graduate students are guaranteed jobs in academia after they graduate,” Diones said. “It becomes all the more important to properly value the years of labor people spend in graduate school.”

And it would take some serious mathematical magic to prove graduate student workers are working less than half time to satisfy the university’s needs.

In reality, most graduate student workers work full time to fulfill their duties as teaching assistants and graduate student researchers – on top of completing research for their theses.

“We are students, but we are doing a job. This is a full-time job,” said JP Santos, an electrical engineering doctoral candidate and vice president of external affairs for the 2019-2020 Graduate Students Association.

Per Santos, most graduate student researchers spend at least 40 hours per week on research. Part-time employees are only expected to work 35 hours per week.

Though the university provides tuition remission for graduate student workers, some would consider this a Trojan horse.

Like 21st century feudal lords, the UC traps student workers in a form of indentured servitude to work off the tuition they owe the school through jobs in labs or classrooms.

This tuition remission is not sufficient payment for this work, though.

“Students’ rights are workers’ rights, and students’ rights are human rights,” said Zak Fisher, a law student and president of the 2019-2020 GSA. “Every worker deserves proper benefits with their job, and part of proper benefits should be Social Security and Medicare.”

Fisher added that in addition to tuition remission, the average graduate student receives about $20,000 to $25,000 per year through employment and loans. University housing alone costs about $18,000. This means there’s hardly any money to cover living expenses, let alone support a family. That has harsh consequences for students with dependents.

And while tuition waivers are supposed to support graduate student workers’ academics by covering the costs of courses and campus fees, graduate student workers don’t always have enough time to pursue courses they’re interested in.

Instead, many fulfill their unit minimum by taking shadow courses designed to allow them time to prepare their master’s or doctoral dissertations.

“Tuition is a trap the university is putting graduate students in,” Santos said. “Their excuse is that they’re paying for our tuition, therefore they cannot give us full worker benefits.”

The UC’s reluctance to provide student workers fair wages and benefits demonstrates it has a shocking lack of respect for the contributions students make to the community.

“I feel like I am toilet paper,” Santos said. “When I am no longer useful, I am thrown away.”

United against unions

The UC is splitting hairs to avoid cutting checks.

Though the University refuses to recognize student workers as full-time employees, it recognizes their right to unionize.

The irony is palpable: Student workers are supposedly not full-time employees, yet they belong to a worker’s union.

While UCLA is dragging its feet, graduate student workers are being recognized at a national level for their role at universities.

In 2016, the National Labor Relations Board declared that research and teaching assistants at private universities are employees with the right to unionize. As of June, there are recognized graduate student unions at 33 university systems.

This rising number sheds light on growing labor concerns at universities. These graduate student workers are seeking union protections and collective bargaining powers in order to advocate for better pay and fair workloads.

These concerns are falling on deaf ears and closed doors, though.

Fisher said he and 14 other graduate students and members of United Auto Workers Local 2865, the union that supports more than 18,000 UC student workers, were locked out of the chancellor’s office last week while trying to make an appointment. They were delivering a petition with more than 1,000 signatures asking the UC regents not to increase nonresident tuition.

“It is a symptom of a total lack of transparency among the folks who are supposed to be the most transparent and be the exemplars of what it means to run a public institution for, by and of the people,” Fisher said.

Administrators certainly aren’t holding onto the student-first, employee-second attitude for students’ sake. Though there are federal benefits to being considered a student instead of a full-time employee, these pale in comparison to the benefits student workers would reap if their real employment status was to be recognized.

Moreover, the student-first designation allows the UC to minimize student worker compensation. UCLA, for example, assesses a 56% Facilities and Administration cost on funding for organized research. This cost supports research infrastructure and operational expenses, such as lab space and data processing. But student workers feel this cuts into the funds available to support the work they do on these projects.

“The hands of faculty are tied by bureaucrats above them that don’t allow them to care locally for their students because they have all these taxes on their grants,” Santos said.

Santos described a situation in which a company partnering with UCLA wanted to provide $60,000 specifically to support student researchers. The professor, however, informed the organization only $30,000 would go toward students after the F&A cost was assessed. The company decided to take its business elsewhere.

While the university faces significant operating expenses to provide a space for world-class research and learning, it’s clearly ignoring the truth: This is all happening on the backs of student workers.

We need to question this system that places the cost of doing business on students’ shoulders.

After all, running a business involves minimizing costs.

But running a university should not involve minimizing student voices.