Measles was thought to have been eradicated from the United States at the dawn of the new millennium.

Then it came to UCLA.

In early April, amid a nationwide outbreak of the virus, UCLA was contacted by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health with some news: A student at the university had contracted measles.

Measles is a contagious viral infection known to affect the respiratory system, immune system and skin. Symptoms of measles develop after an approximate 10-day waiting period and will progress from symptoms associated with the common cold to more telltale symptoms like cough, rash and fever. If infected, individuals are contagious for four days both before and after the rash appears.

James Cherry, a distinguished professor of pediatrics at the David Geffen School of Medicine, has spent more than 40 years working in fields of infectious diseases and epidemiology. Cherry emphasized the importance of the measles vaccine and two consequences of the measles infection that are often overlooked: the potential for a subsequent development of a neurologic disease and an up to three-year period of increased risk of developing other diseases.

The neurologic disease mentioned by Cherry is subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, which can lay dormant in a person’s brain for over eight years after they are infected with measles. If developed, the disease is fatal, Cherry said.

Thus, measles clearly poses an incredible threat to those that develop it. However, people continue to give the disease opportunities to do so.

“A concern today is there’s so many anti-vaccine people that in some areas in little pockets in California, among other places, … if it comes, it’ll spread to two or three generations of people,” Cherry said.

The vaccination currently administered to combat measles is the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that children get two doses of this vaccine to achieve the maximum protection.

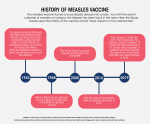

Although the vaccine has demonstrated success, the process of developing an effective vaccine was arduous.

The measles vaccines Rubeovax and Pfizer-Vax Measles-K were licensed in 1963, but there were some complications. Rubeovax was said to be 95% effective at preventing measles, but it came with many side effects. Pfizer-Vax Measles-K resulted in fewer side effects, but in turn was much less effective.

After many different vaccinations cycled through, Merck’s Attenuvax was approved for use in 1968 and is still in use today in the MMR combination vaccine.

Due to the vaccine’s success, measles was thought to be eliminated from the nation in 2000. However, from Jan. 1 to May 3 of this year, there have been 764 individual cases of measles, according to the CDC. The fact that there were only 86 cases reported in the entire year of 2016 highlights this dramatic retrogression from near elimination.

As per this trend, measles outbreaks still occur despite the MMR vaccine being up to 97% effective. Cherry said that due to the highly contagious nature of measles, over 95% of the population must be immune in order to prevent its spread.

“(It’s) because of misinformed parents that we have not enough children being immunized today,” Cherry said.

Measles is now far from eradicated and has made its return known in many ways, including the recent outbreak at UCLA.

John Bollard, the chief operating officer and chief financial officer at the Arthur Ashe Student Health and Wellness Center, oversaw UCLA’s administrative response to the outbreak.

“We immediately started notifying campus colleagues who would have an interest in this – anywhere from the vice chancellor to (Residential Life) to Environment, Health & Safety,” Bollard said. “(We then) began to crack down exactly where this student had been and when.”

Upon discovering where the student who had contracted measles had been and when, the Ashe Center began working with the UCLA Registrar’s Office to pull rosters for any classes where the student could have exposed the virus. Bollard approximated this to be about 850 suspected cases of contagion at the time.

To clear the list as much as possible, Ashe officials looked at student immunization records. In doing so, the 850 initially exposed students dropped to about 125, all of which did not have immediate proof of vaccination or immunity.

What came next was the LA County Department of Public Health’s quarantine order for anyone who was not able to show immunity.

“As soon as we received the order, we started our own process of notifying the students that they were going to receive official notice from the county,” Bollard said. “(The students) needed to self-isolate or quarantine.”

The 125 suspected cases soon decreased to 25.

As these numbers dwindled, ResLife and UCLA Housing continued to set up a quarantine area in Bradley International Hall. On-site lab teams were brought to the areas in order to conduct blood tests and clear students whose results reflected their immunity to measles.

Then there was only one. Ricardo Vazquez, a UCLA spokesperson, shared in an email statement that the student has since then recovered.

Surprisingly enough, this isn’t the first time that a disease has hit UCLA grounds. Every once in a while, Bollard sees positive tests for tuberculosis. All previous cases were handled quickly by the Ashe Center.

As for measles specifically, this was a first.

“In terms of an airborne infection like measles, we haven’t had a (prior) measles case that I’m aware of on campus,” Bollard said.

Going forward, Ashe is taking multiple precautionary steps to ensure that a similar outbreak will not occur.

As of May 3, Ashe has been sending secure messages via Ashe Patient Portal to notify any UCLA student for whom the system does not have current documentation of measles immunity.

Ashe hosted a fair Tuesday where it provided the MMR vaccine to students at no cost. Lab staff were also in attendance to draw blood and test for measles.

Despite the unfortunate run-in with measles, Ashe hopes to turn it into an opportunity to raise awareness for the infection and get documentation for as many students as possible.

“On a college campus, what you really want is documentation,” Bollard said. “That’s how we were able to get that 850 number down so quickly.”