A single, clenched fist thrust from a sea of white ivory.

That’s the symbol of equity in higher education.

It’s the sigil black students wear when they rise up to challenge an institution that has abandoned them. It’s the rallying cry of union workers clad in bright green, protesting unlivable wages under the sharp Southern California sunlight. It’s the defiant display of solidarity victims signal to each other in the face of rampant faculty sexual harassment and discrimination.

It’s the sign of struggle.

And struggle we have.

Marginalized communities have struggled to fight for more representation in their administration, faculty and student body despite a culture of reluctance and theatrical politics. Students with drastically unmet needs such as housing and food insecurity and mental health concerns have struggled to get help from a university with few resources and markedly fewer for those in need. Underprivileged campus members have struggled to change a system that gravitates toward serving only those with the savings to spare.

A century in, UCLA is still a campus of barriers.

Like other higher education institutions, it’s an ivory tower: It falls short in promoting a diverse campus body, cannot claim to include and retain everyone, and lacks momentum in dismantling structures that hinder equity in the work and academic space.

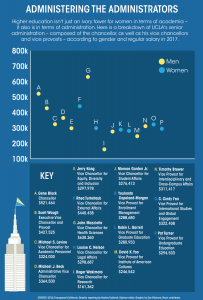

These can seem like idealistic ramblings. There’s no single, sweeping policy that can erase the fact that only 22% of UCLA’s student body is Latino or Hispanic compared to 49% of Angelenos, that more than two-thirds of the university’s faculty are white and that only about one in three of Chancellor Gene Block’s senior administrators are women.

Perhaps that’s why UCLA’s Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion has taken refuge in etching away at incremental policies that five years from now may still make no noticeable difference.

But we’re at a university that touts broad statements like “Build equity for all.” We have to think big and ask the uncomfortable question that so many have indignantly thought when faced with UCLA’s immovable impediments: Who does this university truly serve?

Better put, whose campus is UCLA?

The paradox

Inclusion is tearing apart UCLA – and not for the reasons you think.

It’s because of one word: intersections.

The question of who is truly included at UCLA is fundamentally about who’s sitting at the table and who isn’t. But even that has no correct answer.

Take, for example, the university’s student body. One way to decompose it is to look at its racial breakdown: 3% of Bruins are African American, 28% are Asian, 27% are white, 22% are Latino or Hispanic, 5% are two or more races, 12% are international and the remaining 3% are either American Indian, Alaska Native, Pacific Islander or an unknown ethnicity.

Yet that categorization fails to account for such things as students’ sexuality, mixed race status or income level. Add in those elements of identity, and the simplistic characterization of the campus’ diversity is more complex and confounding.

But even that multifeatured analysis doesn’t consider factors such as students’ country of origin or their parents’ level of education – qualities that can shape people’s educational experiences.

This is the peril of intersectionality. Truly understanding and catering to the needs of the student body requires thinking about the specific experiences each student faces. A black queer man from South Central Los Angeles faces significantly different institutional barriers and forms of discrimination than an undocumented Latina student from Honduras. Both can certainly face similar hurdles, such as racism or financial exclusion, but anyone would be remiss to flatten those identities as simply “students of color.”

But imagine trying to compile a checklist of all the identities represented on campus, along with the unique needs of each microcommunity. Compare that then to what UCLA offers: a generalized center for first-generation college students, an LGBTQ center, an umbrella office for student outreach and retention efforts, a generalized international student center and a generalized office of equity, diversity and inclusion.

It’s hard to find a time in the university’s 100-year history when it made a pinpointed attempt to act on the needs of those with a certain intersectional identity. UCLA created the Academic Advancement Program in the 1970s, for instance, to generically serve first-generation students’ needs. This is in spite of the fact that a first-generation black student’s experiences can’t be homogenized with those of a first-generation Asian American student – one often faces a heightened societal pressure to discount their achievements, while another often faces immense familial pressure to succeed.

Generic services cannot grasp the student body’s nuanced backgrounds. But UCLA can’t spend resources microcommunity-by-microcommunity given its limited capital.

And so, inclusion is a paradox.

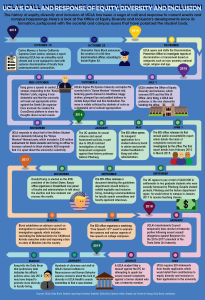

You wonder why UCLA resorts to waiting on students to lobby for their needs – a call-and-response tactic that is bafflingly pedantic.

We’ve seen this play out in recent years. Following the alleged use of blackface at a “Kanye Western”-themed sorority and fraternity party in 2015, Afrikan Student Union members protested cultural appropriation and demanded such things as more black admissions officers and faculty, better anti-discrimination policies and an endowment for black students. Block responded to nearly half the demands a month later, saying UCLA would look to hire more discrimination prevention officers and admissions officers to outreach to black students, create an advisory group to the EDI office and develop more robust anti-discrimination policies, among other actions.

The next year, after a leaked photo of the white undergraduate student body president holding up a gang sign, ASU made a similar list of demands, including mandatory anti-discriminatory competence training for UCPD officers, faculty and staff, money for a black student endowment, creation of a black student financial aid officer and space for a Black Resource Center. The administration didn’t act on many of these concerns.

Fast forward to 2019, and ASU is still making many of the same demands. Yet the resources in question – which would no doubt better serve the black Bruin population – are nowhere to be found.

The same can be said for the Latino community’s calls for resources, including a push for UCLA to admit more students from the community to qualify as a Hispanic-serving institution, which has an undergraduate student body that is at least 25% Hispanic and receives additional federal funding.

The same can be said for many of this campus’ communities.

Cynically enough, it’s clear why UCLA prefers inaction. Creating a Black Resource Center would seemingly necessitate the creation of similar centers for the various other marginalized communities on campus – something the university doesn’t have the money for. And admitting more Hispanic and Latino students would precipitate calls to admit more black students – something the university is seemingly reluctant to do, given the declining percent of black Bruins at UCLA in recent years.

Inclusion has thus, ironically, become mutually exclusive. Not attending to any one community’s needs and perpetuating the systems of oppression that each minority community faces has somehow become the equitable way of dealing with these communities’ problems.

And so it tears us apart.

The politics

The fight for equity shouldn’t be a political game. But UCLA is losing it anyways.

Pretty badly, in fact.

Universities frequently attract political pressure, be it barrages from conservative outlets about how they’re liberal silos that splurge student fees on superfluous diversity initiatives or jabs from hyperprogressive groups that administrators are so infatuated with political conciliation that they are complicit in promoting fascism.

You would think UCLA’s administrators, heralds of America’s top public university, would tune out the noise.

Instead, they’ve kept an ear on the jabber.

Needless to say, the university has come under fire for nearly every remotely equity-related action it has taken.

The diversity course requirement its faculty overwhelmingly approved in 2015 – an effort that began in the 1980s but failed multiple times – was criticized by conservative outlets and some professors as an attempt to brainwash students into political correctness. Thomas Schwartz, a distinguished professor of political science at UCLA, notoriously wrote that the “attitude-altering course” was akin to forcing Norwegians to vaccinate against malaria.

Of course, malaria still doesn’t have a licensed vaccine, Norwegians can most certainly contract the disease if they travel abroad and students are undeniably susceptible to being discriminatory.

But, the peanut gallery has raged on. UCLA’s establishment of the EDI office fueled the right-wing outrage machine. Political grandstanders like David Horowitz, who repeatedly taped racist and intimidatory posters on campus against Students for Justice in Palestine at UCLA, have repeatedly concocted an image that Jerry Kang, the vice chancellor of equity, diversity and inclusion, is intentionally dividing the university and suffocating conservatism.

Policies like mandatory equity, diversity and inclusion statements for faculty candidates and those seeking promotion – an effort that, while noble, falls short in holding candidates accountable for their commitments to these ideals – have been painted as “diversity obsessions” that would have somehow made Albert Einstein a pariah.

Efforts to foster discussion on divisive issues, such as November’s National SJP coalition-building conference, have faced outcry from removed city council members, low-profile U.S. congressmen and Internet commenters alike. Administrators were so influenced, in fact, they issued a cease-and-desist order, threatened shutting down the event and wrote a vague op-ed about the university’s undying commitment to free speech while implying the NSJP event was a closed-door, anti-Semitic rant session. You’d be hard-pressed to find that kind of backflipping for the perennial Ben Shapiro and Milo Yiannopoulos campus events that breathe life into anti-immigrant and anti-transgender sentiments.

Disturbingly so, these gripes have done damage: Campus officials have bought into, if not given credence to, the notion that equity is a zero-sum game and that diversity is performative.

For example, when searching in January for a new director of the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA created a search committee comprised of 11 clinicians and employees – 10 of whom were white and eight of whom were men. The school justified the composition, claiming the three women and one Latino financier met its 25% diversity quota for search committees – a ludicrous argument given the Semel Institute serves the broader Los Angeles community, which is not 90% white or 70% men.

Of course, it might seem that, coincidentally, the most qualified group of faculty for the committee happened to be majority white and majority men. But that kind of thinking is pernicious: UCLA’s faculty are majority white and majority men. Block’s senior administration is majority white and majority men. The highest paid employees at the University of California as of 2017 were largely white and majority men.

Meanwhile, the members of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Local 3299 – the largest UC union, which represents many of the University’s lowest-paid workers – is 79% nonwhite and 56% women.

The ivory tower is truly made of ivory.

Yet, administrators have managed to miss this, instead settling to appease concerns that diversity or implicit bias trainings are coming at the expense of quality or people’s right to hold mistaken opinions. Kang said in an interview that his office has worked extensively to develop an evidence-based approach to justifying its inclusion and diversity efforts, combining social science research with policymaking to win over people.

Changing minds is indeed a component of promoting equity, but when the campus’ leaders hardly represent their constituency, we have to ask: Whose minds really need changing – off-campus critics or senior officials?

The propositions

I’ll be honest: I haven’t really answered the question of whose campus UCLA is.

But it’s clear whose campus UCLA isn’t.

Our campus’ divides largely spring from the university’s bureaucracy. UCLA, like other institutions, prides itself on its slow-moving, democratic way of shaping academia that maintains faculty’s and administrators’ self-governance.

Enacting academic policy, for example, requires the approval of hundreds of faculty across several committees, each of whom can voice concerns and cast a vote. Similarly, vice chancellors and vice provosts tend to stay in their own lane, hesitating to reach beyond the scope of what falls under their offices.

And as of July 1, 2015, UCLA has pigeonholed equity, diversity and inclusion to Murphy Hall 2147.

To be fair, the EDI office has made its mark on campus. It has implemented stopgaps to ensure faculty are less susceptible to implicit biases when hiring. It has, per Kang’s account, potentially improved gender representation among faculty at UCLA. And it has formalized a process for measuring diversity and equity at this university.

But a lot of the work is too invisible or surgically precise to affect faculty hiring procedures.

Equity, diversity and inclusion don’t just apply at the entry points to this university. Manifesting those ideals on a campus as large as UCLA requires an earnest effort on multiple fronts.

It means revamping the diversity course requirement to be more than an annoying checkbox for a subset of students – something other universities have shown is possible. Faculty at Westfield State University in Massachusetts, for example, saw promising levels of student comprehension of intersectionality theory when faculty co-opted curricula to examine diversity and equity through the students’ fields of study – a promising indicator, considering the classes’ majority-white compositions.

It means incentivizing, not mandating, faculty to follow diversity and equitable hiring guidelines, and highlighting the extent to which established university norms – the demand to purchase pricey course materials, limited maternal leave benefits, the looking down on students who don’t immediately come in with the academic skills to succeed – can wall off segments of the population.

It means including a diverse array of voices at the decision-making table, and ignoring unproductive noise from the gallery stands.

Most importantly, it means affirming that the status quo is inequitable, undiverse and exclusive, but making a skeptically self-conscious effort to change that.

Ivory isn’t permanent, after all.