Parenting students and faculty on campus are a forgotten constituency. The voices of nursing mothers have been largely ignored by UCLA, heard only by student activist groups. This column series explores the issues these mothers face and the steps UCLA must take to address these unmet needs.

Sleep-deprived students with bags under their eyes traipse around campus like zombies as final exams and essays roll around, complaining about the difficulty of maintaining a work-life balance.

Parenting students on campus bear double this burden.

And they don’t have the luxury of pulling all-nighters in Powell Library – their children need to be picked up from child care, fed and put to bed before they can even think about studying.

For these parents on campus to attend lectures and study, daytime child care is critical. But many find themselves without child care in part due to the inaccessibility of UCLA’s Early Care and Education centers.

UCLA has three ECE centers that support about 335 children total. Only two serve student families, however. So families struggle without convenient child care as they wait for a spot in an ECE center for up to three years.

UCLA can’t leave students deprived of child care and the ability to succeed academically. The institution needs to expand the child care resources for parents on campus.

There are too many horrifying stories about the sacrifices parents on campus have to make to deal with limited child care options.

LeighAnna Hidalgo, co-founder of Mothers of Color in Academia de UCLA and a sixth-year Chicana/o studies doctoral candidate, put her child on the waitlist for UCLA child care when she was 3 months pregnant.

Hidalgo’s daughter did not receive a spot at an ECE center until she was 14 months old. This means Hidalgo went a full year without child care for her baby.

During that year, Hidalgo was going through qualifying exams for her doctoral program.

“It was incredibly hard and the entire time I thought I would have to drop out of the program,” Hidalgo said.

The amount of stress she was under diminished her milk supply, she said.

“Not only did I suffer, my daughter suffered,” Hidalgo said.

Hidalgo counts herself lucky to have gotten off the waitlist at all – some of her friends could not get a spot in ECE centers until after they graduated. Hidalgo’s second child was given a spot when he was three months old. This discrepancy is due to the differences in demand for and availability of spots in infant and preschool care at ECE centers, according to Deborah Shine Valentine, executive director of UCLA ECE.

Getting from campus to the child care center is also a big concern for student parents. Only two centers, the Krieger Center and the Fernald Center, are on campus. The third, University Village Center, is about 30 minutes away.

University Village Center is the only one that gives enrollment priority to student families receiving state-sponsored financial aid. This means some of the families in the most dire situations face the additional financial burden of an extended commute that can total up to several hours each day.

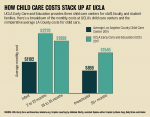

Families also experience financial difficulties accessing UCLA’s child care. The average annual UCLA ECE tuition for infants in affiliated families is about $27,240 and between $18,540 and $23,880 for preschoolers. Across Los Angeles County, on average, child care costs about $14,309 for infants and $10,303 for preschoolers.

“At one point, I was paying more for child care than my rent,” said Paloma Giottonini, a sixth-year doctoral candidate in the urban planning department.

Granted, UCLA is located within one of the most expensive areas in Los Angeles. But that doesn’t mean child care tuition should be so high that it’s inaccessible.

Teaching assistants are making less than what it costs to enroll students in child care, said Maricela Becerra, a fourth-year doctoral candidate in the Spanish and Portuguese department.

“We are constantly worrying about our kids – how to take care of them, how to afford to feed them,” Becerra said.

Becerra has two children, one of whom is enrolled in a UCLA ECE center. She and her partner cannot afford child care for their second child. Her partner has had to work part-time to help take care of their child.

Becerra and Giottonini added this situation is even more difficult for undergraduate students, who do not have salaries to offset the cost of child care and are less likely to know they need to apply to ECE during pregnancy.

Hidalgo said she and two other TAs had to take turns caring for a first-year student’s baby during fall 2016, as the undergraduate mother did not have access to child care. Hidalgo added that without this help, the student would not have been able to pass the class.

Though it’s amazing to see students come together to support mothers, it’s disheartening to realize this camaraderie is needed because current institutional infrastructure does not support student parents.

“If you want to keep mothers in school and help them do well in school, you have to invest in our futures in the same way we are investing in UCLA,” Hidalgo said.

Though there are issues with the accessibility of UCLA’s ECE program, quality is certainly not a problem. ECE is a learning center that provides more opportunities for growth and development to its students than the average day care center does. Hidalgo’s daughter, for example, has learned sign language from the ECE teachers.

But it’s crucial that all parents on campus – and their children – have a fair shot at getting and affording this opportunity for quality and accessible child care.

Valentine is committed to expanding support for parents on campus and collaborating with administrators and parents to do so.

She added that each of the 42 subsidized spots ECE provides costs the university $10,000 a year.

“There are issues with accessibility and affordability of child care for parents on campus,” Valentine said. “It is a problem across the nation.”

Quality child care is complicated to provide. But that doesn’t mean it should be impossible for parents on campus to attain: Their needs don’t disappear just because UCLA doesn’t address them.