Parenting students and faculty on campus are a forgotten constituency. The voices of nursing mothers have been largely ignored by UCLA, heard only by student activist groups. This column series explores the issues these mothers face and the steps UCLA must take to address these unmet needs.

As the sounds of labor strikes this week reverberate around residence halls and on campus, many Bruins are questioning the ways UCLA supports – or fails to support – its employees and students.

Sadly, it is all too easy to find systemic, institutionalized negligence by the university when it comes to caring for the campus community.

One such marginalized group at UCLA includes parents nursing their children on campus. Much like the workers who stepped up to the picket line this week, parenting students have also had to take health advocacy into their own hands to ensure the well-being of their children and protect their basic rights.

UCLA has historically fallen short in supporting parents on campus, failing to provide fundamental childcare resources and spaces to breastfeed. The onus has been on students to stand up for themselves and their children in the face of rampant institutional negligence.

Mothers on campus are given a voice by groups such as the Mothers of Color in Academia de UCLA, Creating Space, the Bruin Resource Center’s Students with Dependents Program and La Leche League.

MOCA concentrates on raising visibility for issues mothers of color and their allies face at UCLA. It officially started in 2014 after a group of graduate students decided to address the lack of resources for parents on campus.

Nora Cisneros, a doctoral candidate in the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, is one of the co-founders of MOCA. Cisneros started her doctoral program in 2012 when her daughter was less than 2 months old, and said she found the campus’ resources for parents were sorely inadequate compared to what she had seen at her other jobs.

“I came with the understanding that a space to nurse is an educational right and a workplace right, but I found a disregard (at UCLA) for a physical need I had,” Cisneros said.

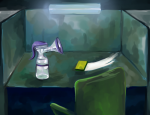

Mothers on campus face unique challenges, like finding the time and space to breastfeed in their busy class or workday schedules. As lactation rooms on campus are inaccessible due to their locations and convoluted lock policies, especially on North Campus, mothers are forced to pump in areas that are unsanitary and uncomfortable.

“I nursed wherever I had to, whether it was in a library or a bathroom,” Cisneros said. “I knew I had to maintain the milk to keep my daughter healthy and because I could not afford, nor did I want to use, formula.”

Pumping in a bathroom, which is often the only viable option left to mothers on campus, is far from ideal. Women are supposed to breastfeed in areas that are sanitary enough for food production, as their milk will be used to feed and nourish their children. A cramped stall just feet from a toilet certainly doesn’t fit that bill.

Cisneros said she found it miraculous she was able to nurse her daughter for a year and a half despite the conditions she faced on campus.

“The first two months, it was physically painful to not have her on me latching and getting the milk out. I experienced multiple health problems and also strong emotional distress,” she said. “I wouldn’t wish that on anybody.”

Cisneros isn’t the only mother with horror stories.

JoAnna Reyes Walton, a graduate student in the department of art history, also struggled to care for her son because of the lack of adequate campus resources.

“My milk production dropped at UCLA,” Walton said. “I continued to nurse my son but I wasn’t able to provide as many bottles as I should have because I wasn’t able to pump throughout the day.”

Walton added that nursing is especially important to graduate students because they often cannot afford formula, which can cost up to $1,500 for the first year of a child’s life. This means the inaccessibility of lactation rooms at UCLA isn’t just inconvenient; it also compromises the financial security and health of mothers and their children.

“Being a single mom on campus, I have realized there is a lot of inequity and there is a lot that UCLA could be doing for parenting students,” Walton said.

MOCA was created because of these types of experiences. The group has lobbied the administration and worked with campus entities, presenting information to the UC Students of Color Conference, the Graduate Students Association and unions.

MOCA has pushed for a needs assessment on campus and developed a petition, which has since been signed by more than 800 people, that calls on UCLA to address the unmet needs of parents on campus. The group has also fought for several improvements on campus, including getting UCLA to hire lactation specialists and the Ashe Student Health and Wellness Center to stock pumping supplies.

Additionally, MOCA led a march for Día de Las Madres in 2016 that inspired the Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion to start acting on the group’s message.

While this grassroots organization is a testament to student activism and resilience, it also represents the failures of UCLA to support its own. Mothers should not have to take time away from their school work and their family commitments to ensure they’ll be able to feed their children while on campus.

UCLA said in a statement that it supports nursing and pumping mothers.

“The university has work to do … to make lactation spaces more available and accessible,” the statement said.

And the university has a lot of work to do. Right now, all of this work is being done by mothers in their limited free time as they struggle to balance families, school and work.

UCLA has allowed for an environment that makes it nearly impossible for mothers on campus to succeed as parents and as students.

Considering that students behind MOCA and other activist groups have made time to clean up after the university, it’s worth asking: Why hasn’t UCLA been able to do the same?

The negligence that UCLA has shown towards pregnant mothers on campus might actually violate California state law. According to the Assembly Bill No. 1127, Chapter 755, any public building owned by a state agency should provide a diaper changing station that is readily accessible to both men in their restroom and women in their restroom. Where are these stations in Powell, Humanities, or Physics and Astronomy Building? Many of these buildings are not outfitted with the stations mandated by the law, and as such school adminstration should be pressured until their facilities meet the standards advanced by the legislature.

Our Bruin mothers deserve better.

Actually the law states that stations are required in both men and women’s restrooms in newly constructed or renovated buildings; existing, unrenovated buildings are only required to provide one changing station. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB1127

But, having said that, universities should not be complying ONLY with the minimum law. They should strive to meet the students’ need, not just the law’s.