This post was updated Feb. 27 at 4:32 p.m.

It’s awards season, which means it’s also the season of naive think pieces questioning whether the era of #OscarsSoWhite has passed.

The answer is, of course not.

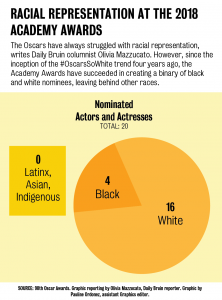

The Oscars were first criticized for their slate of all-white acting nominees in 2015. And over the last four years, the Oscars have started to nominate more black actors. However, the increase in black nominees has focused the conversation largely on a binary of white and black representation, leaving other races behind. In order for the #OscarsSoWhite campaign to retain its relevance, the issue of representation must be expanded to recognize the conspicuous absence of Latinx, Asian and other communities of color.

Ever since #OscarsSoWhite first trended in 2015, nominations have, in fact, been more inclusive. This year, four actors of color have been nominated, including veterans like Denzel Washington for “Roman J. Israel, Esq.” and relative newcomers like Daniel Kaluuya for “Get Out.” The 2018 nominees for best director also include Jordan Peele and Guillermo del Toro, a black and a Mexican director, respectively.

It might be easy to look at the nominees now and think that #OscarsSoWhite is a problem of the past. But the minimal increase in diversity does not mean the Oscars have achieved equal recognition and representation.

The conversation surrounding representation in Hollywood is complex and nuanced, but much of the mainstream coverage in the press has been primarily focused on the black community and their on-screen representation – a focus that makes sense from a structural point of view. African-Americans are one of the larger racial minority groups in the country, and many prominent black actors have made it big in Hollywood – they obviously deserve more inclusion in the Academy Awards.

Comparatively, there are relatively fewer Latinx and Asian “stars” of the same magnitude, and it is incredibly difficult to think of Native American actors who are widely recognized or known. Actresses like Constance Wu and Gina Rodriguez, who are vocal advocates for their respective communities, both tweeted about the lack of nominations of Asian and Latinx acting nominees. But they often appear as lone figures, lacking the same community that black actors have built within the industry.

And while Oscar-worthy films about Latinx, Asian and indigenous characters are few in number, that’s not to say there weren’t any performances worthy of attention. Salma Hayek received rave reviews for “Beatriz at Dinner,” as did Hong Chau for her performance in “Downsizing.” Chau even received a nomination at the Golden Globes, though she failed to garner one at the Oscars.

The academy’s omissions and failures are even worse when one considers its several problematic nominations in the past. For example, the half-Indian actor Ben Kingsley donned skin-darkening makeup for his Oscar-winning performance in “Gandhi,” and Jennifer Connelly received an award for her role in “A Beautiful Mind,” playing a Salvadoran woman.

The Oscars’ erasure of Latinx, Asian and indigenous people is a symptom of a larger problem within Hollywood. In order to right its wrong, the film industry is in need of major, systemic changes that support stories about people of color, by people of color. But one way to move the needle is by making sure that the creation of these films is a part of the conversation surrounding #OscarsSoWhite.

Pushing for the inclusion of other marginalized groups is not a statement that black representation isn’t important. It is, and every well-deserved nomination is instrumental in creating a representative film industry. But the fact of the matter is that other communities of color are still being excluded, both from on-screen representation and the larger conversation surrounding representation.

We have to change how we’re quantifying representation and progress so that we’re not just looking for some form of representation, but instead pushing for equal representation of all races. It’s not enough for just one racial group to reach a position of parity – if there are still people who are underrepresented, then the #OscarsSoWhite campaign has not yet won the battle.

Why can’t the films be judged wholly on their merit and quality? Why do we insist on including the filmmaker’s race and ethnicity as part of the judging criteria? Would you disagree that selecting or rejecting people because of how, where, and to whom they were born rather than the art they create epitomizes racial discrimination and bastardizes the work?