Nothing kills a dinner table discussion better than a conversation about policing in America. Add in a comment about our mental health care system, and you might as well pass on dessert.

Mental health-related police encounters can be dangerous, and have the potential to end in tragedy. And in the line of duty, they’re a part of the everyday bread and butter.

“It’s almost something we come across on a daily basis” said Lt. Kevin Kilgore of UCPD. Even among the people it oversees – students, faculty and citizens in the Westwood area – UCLA’s police and people with mental health issues regularly come into contact.

In the city of Los Angeles, encounters between police and people with mental health issues haven’t always ended peacefully. In 2015, more than a third of all police shootings involved people with mental health issues. This fraction did decrease to one-seventh in 2016, indicating some improvement in policy. However, individual incidents still occur in LA and across the country: In May, for example, a police sergeant in New York was charged with murder after he shot and killed 66-year-old Deborah Danner, who had written about her schizophrenia.

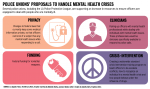

In response to this shooting, the Los Angeles Police Protective League, along with several other police unions, joined a national effort to increase federal funding for training police to prepare for interactions with people who have mental health issues. The initiative, called Compassionate and Accountable Responses for Everyone, calls for the creation of national training standards and support for hybrid teams composed of law enforcement and medical professionals.

This proposal should be seriously considered. The federal government should implement national policing standards and fund the inclusion of mental health care expertise in police departments across the country. This would improve interactions between police and people with mental health issues.

Expert-approved training standards are crucial for dealing with mental health. Officers have to analyze a number of different responses and behaviors by people with mental health issues within incredibly short periods of time. They need to be able to read a situation, as the same action can provoke a different response in people with different illnesses.

Mental health training is generally focused on de-escalation techniques. Officers need to be able to give off the proper verbal and body language cues – speaking in a calm voice, providing personal space – in order to bring people in safely. These techniques can sometimes serve as viable alternatives to the use of force.

“I found that finding things that made someone smile or piquing their interest in a positive way, helped me be able to establish a relationship with folks that always ended in something positive,” Kilgore said when speaking of his experiences de-escalating situations involving people with mental health issues.

Large, centralized bodies, such as California’s Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, can develop training procedures and standards so that smaller departments themselves don’t have to focus on the legwork of developing them. The same would apply to a national equivalent.

The spread of common practices at the state level allows better interoperability between police departments, big or small. With federal standardization, police officers from different regions of the country could more easily work with one another. Collaboration between departments would also result in more real-world testing of mental health-related techniques and increasing the methods’ effectiveness.

Along with well-researched training standards, some departments are fortunate enough to work directly with mental health professionals in what is known as the “crisis intervention team” model. As a part of it, brains from several fields – from psychiatry to human resources – assist officers in the field and allow them to make more effective and safe decisions.

In the crisis intervention model, detainees with mental health issues can also be diverted away from the criminal justice system and into psychiatric care. California law already obligates that officers place contacts deemed to be a danger to themselves or others on hold for a psychiatric evaluation. Research suggests that this practice increases use of health services, and that specialized training in general reduces use of force and arrests in certain cases.

Unfortunately, not every department across the country has the resources to implement the crisis intervention team model. Not implementing it puts both officers and the public at greater risk, but some departments may simply not be financially capable of, or willing to, put these policies to practice. Providing funding for these at a federal level would propagate the model and allow for better handling of mental health problems.

Of course, the CARE proposal isn’t entirely without issues. The unions participating in the initiative have called for access to the mental health records of people encountered in the field, information currently barred to officers by federal law. But records access would be a step in the wrong direction. Even if such access was restricted to a person’s mental health information, the potential for a violation of privacy rights would exist.

Implementation of the other parts of the proposal is worth the financial cost. The funds would provide for standardization and the inclusion of mental health experts in law enforcement. These have been proven to be effective in managing mental health-related problems.

Mental health standards and training have the potential to improve the condition of friends and family with mental health issues. Maybe then, discussions about policing might become a bit more pleasant.