Like clockwork, Jim Harrick’s cell phone buzzed on April 3.

So did those of other members of UCLA’s 1995 men’s basketball championship team, like Ed O’Bannon, Tyus Edney and Steve Lavin.

Another year, another text from Tony Luftman, a manager on the 1995 team, with the same simple message:

“Thank you for letting me be a part of your team.”

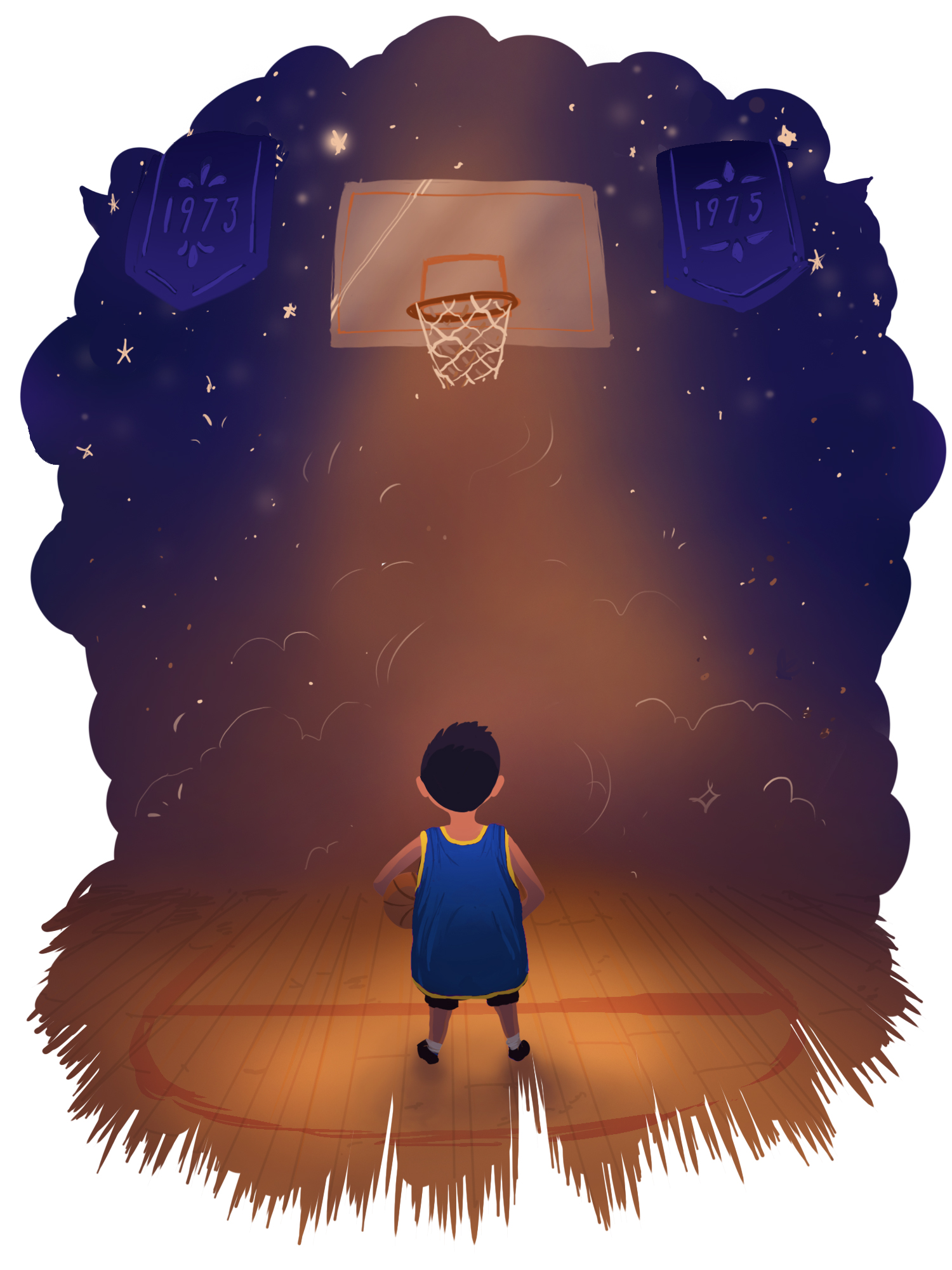

But more than 20 years ago in 1994, Luftman hadn’t yet developed into that reliable friend. He was just another wide-eyed rookie on the team – a college freshman who had failed his first big test.

It wasn’t a history midterm or a pop quiz in math, but in a meeting with one of the best teachers UCLA had to offer.

The invitation didn’t seem real: a dinner with legendary coach John Wooden.

The manager found himself sitting anxiously in Wooden’s Encino condominium, meeting the legendary coach for the first time and describing the transition to life as a college student.

“Well, I’m just a manager,” Luftman said before Wooden abruptly cut in.

“Well, I’m just a coach,” Wooden said, pausing before he went on. “Tony, ‘just’ implies a sense of diminished value or importance. No one is ‘just’ anything.”

So he wasn’t “just” another basketball manager.

He was a crucial component in UCLA’s 1995 championship run to an NCAA record 11th national title.

“Wooden talked about a train, and that you needed every part of a locomotive to go down the track,” Luftman said. “Helping the team was my way of contributing. I wanted to be out there to help the players focus on playing and the coaches to focus on coaching.”

[Related: Basketball manager united friends and family through cancer battle]

Just like different people were needed on that championship team, different experiences and memories at UCLA needed to come together to help Luftman grow as a person.

Even before Luftman, now a broadcaster with the NHL and MLB networks, stepped foot on campus as a student, UCLA and the basketball program were shaping his future.

The Southern California native had attended game after game with his season-ticket holder parents, learning about and admiring Wooden’s 10 national-championship teams.

It was during one of these games where a bewildered young Luftman stared at the baseline, puzzled by the odd number of ball boys on either side.

He met Steve Harris, UCLA’s then-basketball manager, who offered to let him be a ball boy against Louisville the next week. Luftman accepted, but not before telling Harris his future plans.

“One day, I’d like to be a manager,” he said.

Ball boy duties turned into working UCLA basketball camps in the summer. Summer camps turned into an offer to attend UCLA as the team’s manager.

For Luftman, being a Bruin was within reach.

He was ready for the Westwood of his imagination – walking where Jackie Robinson walked, playing where Kareem Abdul-Jabbar won championships – a filtered and picturesque UCLA experience.

It didn’t come as easy to him at first.

The reality was slogging through English discussions, navigating the dating game and embarrassing himself in practice almost daily.

Some days he fell flat.

During one practice, a distracted Luftman chatted away with then-assistant coach Steve Lavin before noticing the shot clock, which he had been tasked with monitoring, was about to sound off in three seconds, 60 feet away from where he was sitting.

The “Mission: Impossible” theme went off in his head.

Luftman sprinted for the other end of the court, diving for the clock in a futile attempt to stop the horn from blaring in Pauley Pavilion, before falling on his face.

Practice paused, players stopped their drills and Harrick turned towards the crash.

“Luftman, what the hell is going on over there?” Harrick said.

“Sorry coach, my fault!” Luftman said.

Humiliating or not, the embarrassment didn’t kill him. Those memories, good and bad, laid the foundation.

Whether it’d be remembering that Edney couldn’t eat gummy bears for fear of a stomachache, that O’Bannon had a soft spot for the Little Rascals and preferred Cheetos over cheese puffs or Wooden lecturing him on the importance of word choice, each story fostered a friendship and each memory was stored away for later.

But few memories could top the electrifying feeling of walking in with the team and cheering on his friends in Pauley for the first time.

“It’s the closest I’ve come to having a heart attack,” Luftman said. “I thought I was going to die the first time I walked out. The cheers, the roaring, the 8-clap. You can’t duplicate that.”

Two memories did top that one, though – his independent study course with Wooden was one, the national championship win with his friends was the other.

Every week, Luftman trekked to Wooden’s home, where photographs of the championship teams and the coach’s former players hung on the walls, to sit down and learn from the Wizard of Westwood.

Nothing was off limits during those lessons.

Wooden offered advice on relationships – “It’s OK to disagree if you disagree agreeably” – and coaching. The former coach said he felt guilty about setting such a high standard for future coaches like Harrick, Lavin, Ben Howland and now-coach Steve Alford. Luftman soaked in every eloquent answer.

There was still that one question he was itching to ask Wooden though.

“Coach, what was it like to win your first championship?”

Wooden began quoting Abraham Lincoln and Mother Teresa to Luftman, who was just thrilled with getting an answer from his hero and not quite registering what the UCLA legend was truly saying.

Thirty-one wins later, Luftman had the chance to answer that question on his own.

The Bruins were on the cusp of winning their first men’s basketball championship since 1975, Wooden’s last championship before he retired.

“We believed we were going to do something special,” Luftman said.

Coach Harrick believed that, too.

In a team meeting before the team flew to the Final Four in Seattle, Harrick pointed up at the banners and reminded them they had a chance to get number 11.

They did.

With an 89-78 win over Arkansas on April 3, 1995, UCLA ended the season with the championship trophy. With a pep rally and banner reveal ceremony underway at Pauley Pavilion two days later, Wooden had a question for Luftman.

The coach looked for him first and shuffled through the crowd toward the manager who stood in the right back corner of the room.

“He said with a wink, ‘Tony, congratulations. How does it feel to win your first national championship?'” Luftman said. “Instead of coming up with a two-minute answer, all I could say was ‘It’s really cool, it’s really cool.'”

Luftman returned to electric, raucous Pauley Pavilion as a fan when UCLA took on Arizona this year, reminiscent of his college days.

But he wished he had one more game as a manager.

“When (Pittsburgh quarterback) Terry Bradshaw went into the hall of fame, he said, ‘What I wouldn’t give to have my hands under (Pittsburgh center) Mike Webster’s butt one more time to take a snap.’ I remember thinking, that guy’s crazy,” Luftman said. “But when I was at the Arizona game, I was thinking, ‘What I wouldn’t give to walk out of that door and onto the court with my friends.'”

Instead of sitting on the bench, he greeted Tanya Alford, coach Alford’s wife, who said it was about time UCLA got another banner to hang in the rafters.

He agreed before pointing to the one of the banners floating up top, describing that season to his wife.

“We were something.” Luftman said. “There’s a quote from a hockey coach before the Stanley Cup finals: ‘Win today and we walk together forever.'”

Whether or not the Bruins win another championship, that 1995 banner is permanent proof that wherever Luftman and his team walk, they will always be something.

Beautiful! Thanks for this story, GO BRUINS 🙂