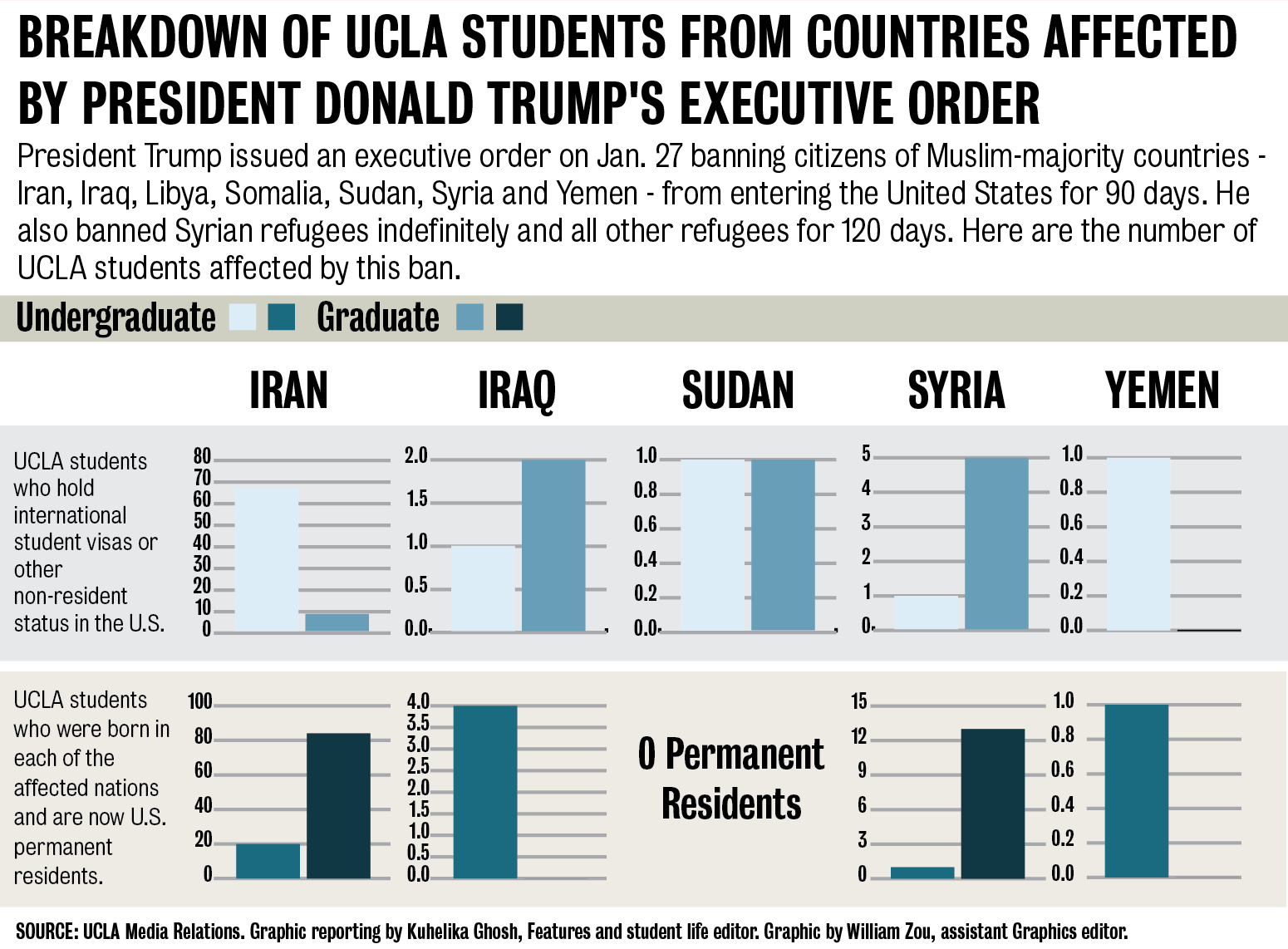

About 150 UCLA students have been directly affected by President Donald Trump’s travel ban on citizens and refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries.

A federal judge from Washington ordered a temporary restraining order on the ban Friday, but it is unclear whether the ban will be enforced. Students from Iran and Sudan spoke to the Daily Bruin about how the ban is affecting them and their families, and their worries for the future of international Muslim students in the U.S.

* * *

An officer at the U.S. Embassy in Dubai accused Soheil Kashani of being a right-wing extremist when he learned Kashani was from Iran.

“I thought he was joking,” said Kashani, who was trying to receive his passport from the embassy so he could return to UCLA at the end of winter break. “Then he literally told me that all the people that come from my city are bad people.”

Once he was able to return to the U.S., Kashani, a fourth-year civil engineering student, didn’t think he would face the same discrimination in America.

But three weeks later, Trump issued the travel ban and Kashani learned it would prevent him from returning to the U.S. if he left again.

“It’s nothing new to the Persian community that we’re oppressed in these ways, and it’s not just Persians either,” Kashani said.

Kashani didn’t receive his visa and passport from the embassy for over a month because of the change in administration, which led him to miss his flight and first week of classes, he said.

Because it’s uncertain if the ban will be lifted or last longer than three months, Kashani worries he will be unable to attend any of the American graduate schools he has applied to.

“I know a lot of people who’ve been left behind (overseas), who probably won’t be able to finish their degrees if the ban lasts for three months,” he added.

Kashani said everyone he knows in the Persian community is stressed because the ban was so sudden and unexpected.

He added he fears restrictions against immigrants and international students may escalate soon.

“What if there is a deportation for Iranians?” Kashani said. “It’s just a possibility, but this (travel ban) was a distant possibility too, and now it’s happened … what if they just start kicking people out?”

Kashani’s parents decided not to come to his graduation in June because of the ban.

Kashani said he feels the travel ban is contrary to American values.

“Us Iranians … do not expect not to be treated like all other students are, and we come here knowing that we’re limited in terms of freedom of mobility,” Kashani said. “But we still choose to come here even though all of us have offers from universities in different countries … because we know America’s different.”

Kashani added most people he knows have told him they oppose the ban, even his Republican acquaintances.

“All my friends have been supportive and it’s very heartwarming,” Kashani said.

Faced with the prospect of being unable to remain in the U.S., Kashani said he has begun applying to graduate schools in Europe, even though it is late to apply to most schools.

“Sometimes I just question my sanity, and ask, why did I come here?” Kashani said.

Sara Kashani followed in her brother’s footsteps in attending UCLA, but she has already started looking at other places to finish her undergraduate degree because she feels unwelcome in America.

Sara Kashani, a second-year neuroscience student, said she fears her parents will make her move back to Dubai if the ban lasts longer than 90 days because they are concerned about their children’s safety in America.

“I’m really scared right now; I feel like my life is up in the air,” she said. “Everything I have is at risk, even my education and I don’t even know if I will be allowed to finish it.”

Her brother will finish his degree in June 2018, and because of the ban he will most likely not stay in America for graduate school. Sara Kashani, on the other hand, will have to figure out what to do for the remaining years of undergraduate education.

“My mom was very mad when she heard about (the ban) because she didn’t want us to move to America in the first place,” Sara Kashani said. “She just wanted us to be together as a family, home in Dubai.”

* * *

Nis Hamid, who has lived in the United Arab Emirates for more than 10 years, said she feels stuck in America as a result of the travel ban.

If Hamid does not return to Abu Dhabi in two weeks, she will have to live in her home country of Sudan, where she has almost no family. However, if she leaves the U.S., she won’t be able to return to finish her degree.

Hamid, a second-year global studies and political science student, is allowed to live with her family in Abu Dhabi because they are sponsored through her father’s job, she said. Her sponsorship will become void if she does not return to Abu Dhabi every six months.

“I lose my sponsorship if I don’t go home, but if I go home, I can’t come back,’’ Hamid said.

She added her initial reaction to the travel ban was to write a post and try to make light of it on Facebook.

“If anyone wants to get married and get me a green card, that would be great,’’ Hamid posted on Facebook.

But right after the news broke, Hamid, who said she has an anxiety disorder, suffered a panic attack during her job as a campus tour guide.

Hamid said she locked herself in a bathroom stall and cried before her boss came and helped her through the panic attack.

Hamid’s father, brother and sister have never been to the U.S., and she said she fears that now they never will.

“My dad tells me to try not to think about it … he is just trying to keep me calm,” Hamid said. “I’m afraid this will be a permanent thing.”

Hamid added she expected a ban to happen, but did not think it would happen so soon.

“The thing I’m most scared of that haunts me is if I go to a government building where I have to show ID, I might be deported,’’ Hamid said.

However, Hamid added she feels blessed to be in California because of the support the University of California system is showing to international students. She remains hopeful the ban will be lifted within the next 90 days.

* * *

Deeown Shaverdian is an American citizen but worries he might never be able to visit the country his family is from because of the ban.

Shaverdian, a third-year history and political science student, is the son of two Iranian-born refugees who are ethnically Armenian and came to America in the 1990s.

“I am worried about not seeing my family,” Shaverdian said. “I have a group of cousins in Germany who moved there as refugees, and I can’t see them until this ban is lifted.”

Being both Armenian and Iranian, Shaverdian said he has always felt a strong community around him in Los Angeles, but feels upset and betrayed by the U.S. government.

“It felt as if … you (become) a second-class citizen in a country you have called home for two decades,” Shaverdian said.

Shaverdian added the travel ban came as a complete surprise to him and made him angry because he never believed Trump would target a specific group of people.

Although he’s a U.S. citizen, the ban has made him fearful that he won’t be able to go to Iran, which he has never visited.

“Iran is one of the most beautiful countries, filled with some of the kindest human beings,” he said. “I will still cling to my dream of one day visiting (the) country.”