What sets UCLA apart from USC, we tell ourselves, is that this campus provides education for all, while that other school does so for the privileged.

Indeed, there is perhaps no greater insult to a public university’s stakeholders than it adopting the most-maligned practices of private institutions – namely, compromising the admissions of deserving students for the rich, well-connected or otherwise dubiously qualified.

That’s why the outrage was nearly universal when the California state auditor found in March that the University of California has been admitting fewer qualified local students in recent years to admit greater numbers of out-of-state applicants to deal with consistent declines in state funding.

This belief – that the UC should serve Californians first – that underpins the outrage didn’t come out of thin air. It’s at the heart of the 1868 Organic Act that founded the University and has been continually reinforced by influential leaders in the many decades since. We’ve come to understand that the UC, as a public land-grant institution, predominantly aims to provide accessible higher education for the state and its residents, above everyone else.

Yet, in a since-forgotten revelation from 20 years ago, the Los Angeles Times and the Daily Bruin both found that UCLA was putting the desires of a few over the needs of many by giving extra consideration – or even reversing rejections – for applicants with well-connected or wealthy parents.

Call it UCLA’s own USC phase – a school sometimes unduly criticized for being a playground for the rich.

While UCLA was in the midst of a large fundraising effort during the time – as it is now, with the Centennial Campaign – the LA Times found that university top brass in Murphy Hall were being constantly inundated with requests from politicians, wealthy donors, wealthy donors to-be and even an LA Times editor to give their child or relative’s application a better look. Sometimes, they heeded. Shockingly, university officials vigorously defended the legitimacy of the practice.

In the most egregious case detailed in the Times report, an applicant – a nephew of a Saudi oil sheik – was rejected by both readers until then-chancellor Charles E. Young personally intervened to reverse the decision. His SAT score of 700, around 1050 in the modern standard, wasn’t even enough to get into many California State University schools, and was certainly lower than those of thousands of other applicants in the pool.

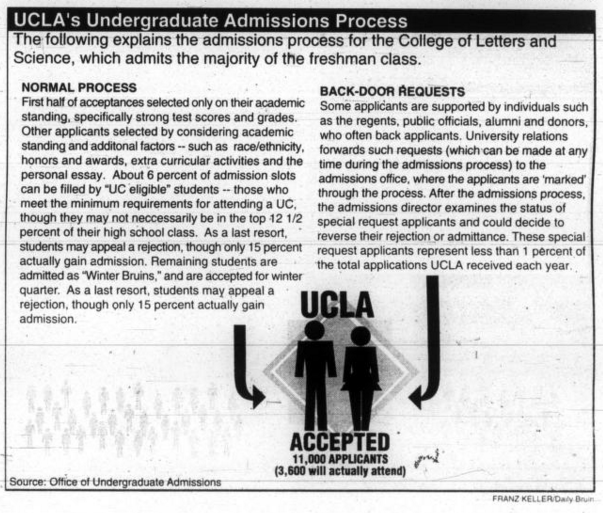

A separate investigation by the Bruin revealed what came to be characterized as a two-track system for admission to the College of Letters and Science: an informal “back-door requests” process utilized by the wealthy and well-connected, and the regular admissions regime for everyone else. This application of the UC’s little-known “special action” admissions resembled the old quota systems for underrepresented minority applicants that were contested and struck down in the UC Regents v. Bakke supreme court case of 1978.

While this massive breach in what was seen as a largely meritocratic process must have been just as outrage-inducing as the state auditor’s findings on out-of-state students are for us, the whole incident was overshadowed by a much more charged debate over the 1995 ban on affirmative action passed by the UC Regents, which was a historically unprecedented decision, since the board typically does not decide or influence admissions policies.

The two events found an unlikely connection, though, since the Bruin investigation found that some of the regents who voted to end race-conscious admissions tried to use their own influence to sway the process in their own favor. It smacked of hypocrisy, to say the least – wealthy and powerful figures opposing greater accessibility to the UC for the disadvantaged in one moment and and wielding their influence to benefit themselves in the next.

1996 is best remembered as the year Proposition 209, which banned all race-based preferences in state government, was passed by the voters.

Both these events, in their own wildly controversial ways, have contributed to a common-sense belief that admits to UC campuses have earned it on the dint of their own hard work instead of who they know or characteristics of who they are. It may only be a matter of time before this idea shifts once again.