Women are not allowed to own a car, let alone travel, in Saudi Arabia.

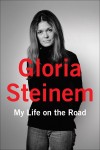

Traveling is a revolutionary act for women, wrote Gloria Steinem in her autobiography “My Life on the Road.” It’s no wonder, then, that the famous feminist has led a nomadic life.

Steinem, 81, worked as a freelance journalist, co-founded the feminist Ms. magazine and toured across countries to organize political movements and deliver feminist lectures.

“My Life on the Road” engages readers on a journey through truck stops with homemade food, 24-hour poker games and Thanksgiving dinner with Frank and Barbara Sinatra in their Las Vegas mansion. Even though sometimes the book feels like a surreal collage of completely different stories, the readers are always kept piously engaged.

The autobiography is a balanced mix of Steinem’s personal life and her activist work that passes down the wisdom she has gained from people she encountered on the road. It is a collage of anecdotes about everyone from female villagers in railway cars in India to U.S. presidents and Native American steelworkers.

In the midst of the surreal chaos, readers are introduced to improbable characters straight out of a Jack Kerouac novel, like a female taxi driver with photos of Lord Krishna, the Virgin Mary and her five ex-lovers in her cab.

Steinem offers readers a tour of her life which lands them straight in the middle of history-making. The readers become part of the massive crowd around Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963 when Mahalia Jackson shouts at him “Tell them about the dream, Martin” and unknowingly changes history forever as she gives rise to the iconic “I Have a Dream” speech.

Steinem’s honesty creates a precious, emotional bond between writer and reader.

At times the content becomes deeply personal as readers turn into Steinem’s trusted confidantes. Steinem expresses her guilt for not being near her father in his final days and mourns the loss of her close friend Wilma Mankiller, the first woman to be principal chief of the Cherokee Nation.

As the book traces her itinerant life, it inevitably traces the rise of the feminist movement as well. The 1977 National Women’s Conference in Houston marked the first steps of both Steinem’s activist career and the feminist movement of the ’80s. The recollection of her subsequent involvement in the National Women’s Political Caucus and the Equal Rights Amendment campaign takes readers on a journey through feminist history.

Particulates of the feminist history are sometimes unknown to the public, and Steinem’s memoir does a magnificent job bringing such landmarks of social change to the forefront.

When Steinem started her career as a political organizer, Congress was only 2 percent female. Her talk of contraceptives and abortion earned her the title “baby killer,” and college students were punished with curfews to avoid rape.

“My Life on the Road” is a wake-up call that equality has not yet become reality. Fifty years later, women are still underrepresented in Congress, stigma still accompanies abortion and sexual assault is still prevalent on college campuses. Steinem’s memoir should act as a motivational force for our generation to carry on fighting for gender equality.

“My Life on the Road,” however, is not a feminist treatise. It’s like an archive of personal stories that spans across countries and decades.

Personal tribulations, political games and peculiar anecdotes are all mixed in the memoir, which is as chaotic as life itself.

Steinem shares her most important piece of wisdom: No woman has to miss out on the journey in order to build a home. And as she balances her life at home with her life on the road, she sets the path for more women to follow.

– Suzie Papantoni