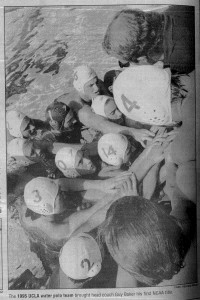

Top-ranked UCLA, sporting identical blue and yellow robes, lined up in front of a glossy pool and an audience of Bruin and Golden Bear fans on Oct. 24.

For a group of middle-aged men, all wearing identical blue T-shirts and watching from across the pool, the scene was nostalgic.

Twenty years ago, they had stood in a line with the Golden Bears before the 1995 NCAA championship game.

Unlike today, Bruins once stood next to their powerhouse opponents before games as underdogs, and usually left the pool deck an hour later in the same fashion – members of a program that hadn’t brought a trophy home to Westwood for two decades.

The tides turned in 1995 when UCLA defeated Cal for the national title.

The victory transformed not just UCLA water polo dynamics, but collegiate water polo hierarchy. On Oct. 24, the players and coaches that comprised the 1995 team were welcomed back to campus and introduced in front of Bruin and Golden Bear fans once again.

A leap of faith

In March of 1991, UCLA dropped men’s water polo due to budget restrictions.

Alumni and boosters attempted to raise money to restart the program, but by the time they had earned a $100,000 endowment, three months of damage were already done. Top players, faced with nowhere to train, had departed to pursue other interests or transfer to other programs.

Candidates for the new coaching job that year were wary of starting from scratch – except Guy Baker.

A former All-American during his playing days at Long Beach State, Baker accepted the job and promptly guided the men’s team to a second place national finish in his first year.

In 1991, 29-year-old Baker was one of the youngest coaches in NCAA history.

“He took a leap of faith,” said former goalkeeper David Dowdney. “He was brought in and agreed to to take the job on a program that was dropped and was being brought back with no funding.”

Recruiting for a new team in 1992 wasn’t easy. Highly touted high school players usually had their sights set on the more prestigious programs at California and Stanford, but Baker convinced a few top talents to take a risk.

“We came to this program at a time when it was not cool to come to UCLA,” said Adam Krikorian, a freshman in 1992 who later led the Bruins men’s and women’s teams to 11 national titles as UCLA’s coach. “It had been 20 years since they had won a championship. … There was a lot of negative connotation with the letters UCLA.”

There was no university funding, no abundance of scholarships to hand out, no upscale Spieker Aquatics Center to use for practice or hosting games and no recent national titles.

“We knew we didn’t have as much outfitting, we knew we didn’t have as many scholarships, but we never talked about it – it was never addressed,” Baker said. “We were just going to be the best program that we could be and we could compete. … We never took time off to say, ‘This is a reason we can’t be successful.’”

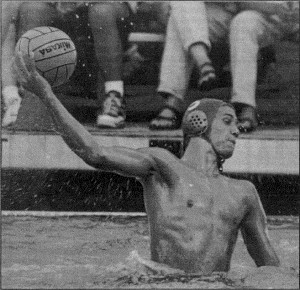

With a few standouts, including junior goalkeeper Matt Swanson, junior center Jeremy Braxton-Brown and junior driver Jim Toring, the team harnessed a competitive vigor from the struggles and losses they’d endured leading up to the 1995 season.

“We got our butts kicked for a couple of years,” Krikorian said. “We took a lot of lumps and bruises, but it heartened us, it toughened us, it made us want it even more. Ultimately it brought us together. … I think that’s the thing that we are most proud of.”

The game

When UCLA defeated USC in the semifinals, the Bruins advanced not only to the national championship, but also to an anticipated rematch against Cal.

UCLA had been in the same situation in 1991, but left with nothing more than a withered hope of reaching that same national stage again.

1995 was different.

“As we went into that game, I think we felt that it was destiny. It was our turn to win,” Krikorian said. “We were a very confident group. We had built that confidence over the course of the entire season.”

In the first half, Toring scored four straight goals – a feat almost unheard of in championship-caliber games. Despite the Bears’ offensive ability to make up for lost ground and narrow the Bruins’ lead, Baker trusted that his 1995 team had the resilience and hunger to out-play Cal by the final buzzer.

When, unbeknownst to his teammates, Braxton-Brown broke his nose at set during the third period, he responded just as UCLA had to the years of setbacks leading up to that moment. Rather than sit out the remainder of the game, the injured center scored to break an 8-8 tie with 1:44 remaining. A minute later, Braxton-Brown scored again – this time off a back-hand that sealed the Bruin’s 10-8 victory.

It was the shot heard around the water polo community, Krikorian said.

The win was not just significant in that it ended the Bruins’ championship drought – the location and the opponent also played a role in changing the geography of collegiate water polo.

“Both Stanford and Cal had beaten us. They were the dominant teams when we first started,” Krikorian said. “To do it at Stanford, and against Cal – it was kind of the sign that the tides were turning and we were bringing the championship back to Southern California.”

The legacy

A junior from Woodrow Wilson Classical High School sat on the grass by Stanford’s pool that day in 1995, watching with wide eyes at Braxton-Brown’s backhand shot.

Until that game, UCLA wasn’t on Adam Wright’s radar for college water polo.

“I thought I was going to go to a different place,” Wright said. “That day changed everything for me.”

Wright, the current men’s water polo coach, attributes both his personal playing career and UCLA’s recent successes to those individuals that started with nothing in the early 1990s and four years later brought a trophy home to Westwood.

1995 was a year of change. For the first time, the NCAA Tournament was comprised of four teams instead of eight, making qualifying much more competitive. However, the aftermath of the 1995 NCAA Tournament proved the most transformative – the Bruins’ victory served as a catalyst that changed geographic hierarchy in the sport.

During the 26-year timeframe from 1969 to 1994, Northern California, specifically Stanford and Cal, had combined for 19 championships. Since 1995, UCLA and USC have won 15 of 20 national titles.

“The whole culture of the sport and what was happening to the sport completely changed,” Baker said.

High school talents today are showing increased interest in playing for the Southern California schools – especially after USC’s streak of six national titles and UCLA’s victory in 2014.

“When we won the national championship, it had been 23 years,” Krikorian said. “I personally feel like those years started and turned this program back around in the right direction and got it going to where (Wright) has taken it now. … It’s flourishing and thriving, and we have the best team in the country.”

Twenty years have passed since the 1995 game. Now, snapshots and stories are all that remain of the moments in the pool that transformed collegiate water polo.

Toring, one of the players to be named to the 1995 NCAA All-Tournament Team, was struck by a bus and killed in 1998 while competing overseas with the U.S. National Team. At the reunion, one of Toring’s teammates, with tears in his eyes, presented the fallen player’s father with a remade 1995 championship ring.

The legacy of fallen players and the teammates that survive them was felt not only in the UCLA water polo community that gathered on Oct. 24, but also in the tenacious energy that fuels today’s top-ranked Bruins in their defense of a title.

“I see the athleticism today – incredible. I was (6-foot-4), I was the tallest guy, and now they’re all taller than me, they’re faster, stronger. … They have great pedigree and athleticism,” Dowdney said. “I don’t think we had as much of that, but we had the grit. … I hope that that is what we can bestow on them.”