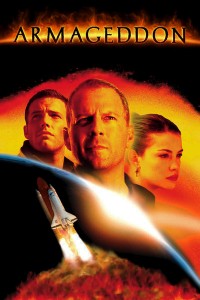

The only solution that Michael Bay’s film “Armageddon” offers, as an asteroid the size of Texas hurtles towards the Earth, is to send Bruce Willis into space with a massive bomb to split the asteroid and save the world.

For Kevin Hickerson, a former postdoctoral scholar in the UCLA physics and astronomy department, movies like “Armageddon” show that the representation of science in Hollywood has been lazy and inaccurate.

“When you blow up an asteroid coming towards us, the pieces would still hit Earth. You’re probably making things much worse – you’d have to pulverize it into a mist to have a chance,” Hickerson said.

In 2011, Hickerson joined The Science and Entertainment Exchange to try and improve scientific accuracy in Hollywood.

The Science and Entertainment Exchange, an organization connecting professionals from science and entertainment, was co-founded by Hollywood director Jerry Zucker and his producer wife Janet Zucker in 2008. The organization has close ties with UCLA, with more than 60 UCLA faculty members contributing to the program.

Janet Zucker said it didn’t take long for her to realize that bringing the two communities together was easier than she had first feared. She said she even found that scientists and filmmakers are really two sides of the same coin.

“Scientists want to think out of the box and sometimes the greatest science happens through discovery – it’s very much like the creative process you engage in when doing a film or television project,” Zucker said.

Rick Loverd, director of The Science and Entertainment Exchange, shares Hickerson’s view that Hollywood didn’t always do justice to scientists in the past.

“If you go back to the ’50s and ’60s, the trope was more of the scientist saving the city from their lab when the giant monsters come, as opposed to being the reason why they come in the first place,” Loverd said. “We’re working towards a return to that point, with less of the stereotypic scientist that would blow up the entire city.”

One of the Exchange’s biggest collaborations was on the 2011 Marvel movie “Thor,” for which Hickerson was asked by the film’s writers to invent a background story for Natalie Portman’s physicist character, create a realistic laboratory as a background for a few scenes and theorize how Thor could travel through dimensions with his hammer. Hickerson said, as a big fan of Marvel films, he couldn’t believe his luck when he learned exactly what film he’d be working on.

Although Hollywood still needs to improve in incorporating scientific advisers into the creative process, the quality of portraying science in Hollywood has definitely improved, Hickerson said.

“For filmmakers, it used to be a calculation of what fraction of the audience would notice or care if something was wrong, and it might have been 2 percent, so they just ignored them,” Hickerson said. “But now with the Internet, that 2 percent could ruin it for everyone, so the storytellers have to really do their homework and make sure that it makes sense.”

Both Loverd and Hickerson believe the improving level of science in movies is also driven by detailed scientific films like “Interstellar” and television shows like “The Big Bang Theory.”

Hickerson said he can even identify the effect of certain scientific advisers that work on these pieces. For instance while watching “Interstellar,” he recognized one of his professor’s homework problems from a class he’d been taking.

“When Matthew McConaughey’s character asked how big a black hole would have to be for you to be able to pass through the horizon, I already knew off the top of my head: 100,000 solar masses,” Hickerson said.

For Loverd, improving the quality of science in Hollywood is not all about correcting mistakes, but also informing people about new advances and raising the next generation’s interest in science.

“I do think there’s a connection between a kid going to see “Iron Man” and getting inspired to be an engineer like Tony Stark, or going to see “Interstellar” and wanting to be part of the first mission crew to colonize Mars,” Loverd said. “(Whatever it might be) there’s a place for a scientist to come in and inform to help build these worlds so that there are no paradoxes or plot problems to get in the way.”