Angela Campos wanted to spend her summer working at the law firm Bergman Dacey Goldsmith in Westwood Village, and when she was offered a spot in its internship program, she said she couldn’t wait to begin.

But before she could start, the firm told her she would need to get class credit with UCLA because the internship was unpaid. Upon meeting with an adviser, she found out that she’d have to pay $1,200 or more in summer tuition fees to get the units for the internship.

“It’s like I had the opportunity to do this great internship, but because of this one rule saying I must get class credit for it, it became problematic for me,” she said.

Campos, a third-year religious studies student, decided not to take the internship, opting instead to work unpaid in her local district attorney’s office and not pursue course credit.

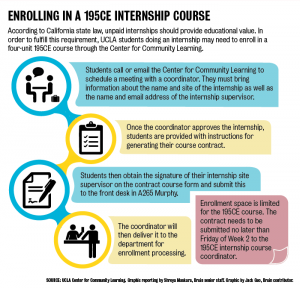

Section 1.04[1][e] of California Employment Law requires that unpaid internships provide educational value in addition to a host of other requirements declared in the 1947 U.S. Supreme Court case Walling v. Portland Terminal Co. To ensure such educational value is being provided, the internship employer must work out an arrangement with the intern’s school.

This typically means the school will offer class credit for the internship, which also means charging students the associated fees for doing so.

For international students, the requirement is more stringent, and students have to get credit for paid as well as unpaid internships to stay in the U.S. on an educational F-1 visa with approval from the Dashew Center for International Students and Scholars.

About 100 students enroll in UCLA’s internship credit course each summer – likely far fewer than the number of UCLA students who take unpaid internships in California over the summer, said Kathy O’Byrne, the director of the UCLA Center for Community Learning, which runs UCLA’s internship program.

The law was designed to prevent students from being exploited for free work by employers. But some said they see the law as unfair to students who cannot afford to pay for units and need unpaid internships to advance their careers.

“It closes doors to people who don’t have the economic standing or can’t rely on their parents,” said Natalie Kreeger, a third-year political science student who has taken unpaid internships in the offices of several prominent politicians including Sen. Dianne Feinstein. “It’s a huge problem.”

How much the law is actually enforced is unclear; some students as well as employers don’t even know it exists.

Each University of California campus manages its internship program independently, and there is no set guideline for how campuses should award credit for internships, said Shelly Meron, a UC spokesperson, in an email statement.

UCLA’s internship program is designed as a four-unit 195CE course offered year-round. The course involves meeting one-on-one with teaching assistants to talk about students’ work and writing an essay about the experience.

“You get to talk to people about your career goals, graduate school, what’s going on with the internship and it’s all by design,” O’Byrne said.

Leonna Choi Luc, a fourth-year sociology student, is finishing her third 195CE internship course spring 2015 and said the process has made her internships more meaningful.

“The TA is an adviser who acts as the liaison between what you learn in college and the real world of jobs,” Choi Luc said.

For some students, finding paid internships to avoid additional course costs is most challenging.

Though some say they feel competition for paid work is increasing, a greater percentage of paid internships is posted to UCLA’s online job and internship application service, BruinView, today compared to when the site first started 10 years ago, said Chris Howell, the employer relations manager at the UCLA Career Center.

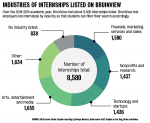

Each year the site gets about 4,000 postings for paid internships and another 4,000 for unpaid, with the unpaid internships heavily concentrated in certain industries like government and nonprofit work, he said.

“As employers compete for talent and students face challenging budget situations, the trend is for more employers each year to offer paid positions,” Howell said. “They don’t want students to be limited by the fact that some students can afford to work unpaid and others can’t.”

Much of the transition to paid internships on BruinView, however, can be accounted for by large media companies like NBC Universal, which each post a hundred or more internships each year and are transitioning from unpaid to paid, Howell said.

For Vishaka Sriniwasan, a third-year computational and systems biology student from India, interning at Amgen, a biotechnology firm in Thousand Oaks, over the next few months will cost her nearly half of her summer earnings. With summer registration fees included, the cost for taking the UCLA course will cost her about $4,000 or more since she is an international student.

“If I had a choice, I definitely wouldn’t take the course. It’s just added workload when I’m already working at this company,” she said. “I’m doing it because I have to do it.”

International students–like most Americans who travel abroad for education–are required to have enough money to pay for living and educational expenses once they arrive in our country. This isn’t new, it’s not something that was sprung on anyone, it’s the way it’s been forever. The attempt to paint international students as economically disadvantaged is really misplaced, in my view. UCLA is first a public university for California students. All others, whether they are international students or out-of-state residents, assume the understanding that they will pay more for almost everything.

The problem highlighted here is not faced by international students only as have been explained above. And yes, international students are fully aware and do accept this but we also pay a much higher tuition rate (all the more relevant with the upcoming tuition hike)which makes up for a major portion of UCLA’s money. Why should we suffer more while even trying to find opportunities for employment? It’s hard enough that all companies we would like to work for don’t even offer interviews for international students and then there is the added burden of paying for tuition while trying to make use of the first class education we receive here.

This problem however, is not UCLA’s fault and has to do solely with the visa requirements. It’s just frustrating and sometimes even limiting in the road to job prospects and future employment.