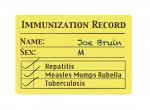

As California is gripped by a sudden spike in cases of measles, conversations about the importance of vaccination abound.

But there’s one specific type of infection – and corresponding vaccination – that is largely ignored in the conversation about immunization, even while it bears critical importance for the college-aged population: human papillomavirus.

Given that one in four students in college have STIs, the importance of adequate knowledge about STI vaccinations is necessary. This is especially the case for information surrounding the HPV STI. HPV is the most commonly transmitted STI among men and women – there are approximately 6.2 million new HPV infections in the US every year – despite being one of the few STIs that has a vaccine commercially available, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV can cause cervical cancer in women and – less often – can lead to other symptoms like genital warts in men.

In 2011, the CDC recommended that children aged between 11 and 12 receive the vaccination for this STI. However, many men and women older than that age recommendation, such as those currently in college, may not be aware of the vaccination’s existence.

On Feb. 2, the Daily Bruin Editorial Board recommended that the UC should quickly enact its additional vaccination plan for incoming freshmen to limit the spread of diseases on campus. Given thatroughly half of all STI contractions occur among college-aged adults, the UC should also require that all its incoming freshmen be vaccinated for HPV within their first year enrolled at the university.

UCLA students can conveniently start the three-dose vaccine course on campus at the Arthur Ashe Student Health and Wellness Center. The cost for the vaccine is $148 at the Ashe Center for students without the UC Student Health Insurance Plan, but it is free for students who are covered under SHIP.

Given that 99 percent of all cervical cancers are caused by HPV, adequate sexual education for this STI is critically important. Through the use of vaccinations, we can limit the spread of this STI and lower the incidence of cervical cancer among women.

Because HPV does not typically cause cancer or produce any symptoms in men, men may unknowingly be carriers for HPV despite being seemingly healthy. Ostensibly, STI-free men and women who do not use condoms but instead opt for just birth control methods, such as an oral contraceptive, are the ones who may be unknowingly spreading HPV.

While cervical cancer is relatively treatable in comparison to other cancers, other complications from the disease may lead to long-term health consequences for women, such as diminished fertility. And just because HPV does not always cause physical symptoms in men, it does not make it acceptable for sexually active men to potentially spread HPV. Men should strive to be responsible sexual partners, and therefore get vaccinated.

Vaccinations are even more important when you consider that there are currently no simple commercially available blood tests that indicate whether people have HPV or not, as there are for other STIs. This means both men and women who have a clean bill of health for STIs may not realize that they could have HPV. Only the presence of visible symptoms, such as cancerous cervical cells analyzed during a woman’s Pap smear, can prove if someone has HPV.

Ultimately, men and women are both responsible for keeping themselves safe during sex, and the HPV vaccination is a good first step in doing that.

Email Patel at kpatel@media.ucla.edu. Send general comments to opinion@media.ucla.edu or tweet us at @DBOpinion.