Editor’s note: Although UCLA is compliant with federal sexual assault laws, six student survivors told the Daily Bruin more needs to be done. These survivors spoke to the Daily Bruin about their experiences with sexual assault at UCLA over the course of six months. All but one survivor requested a psuedonym to protect their identity. It is the policy of the Daily Bruin to grant anonymity to survivors of sexual assault unless specifically instructed otherwise by the survivor. To read the stories they shared with us, click on “Survivor stories.” To read their stories in their own words, click on “In their own words.”

Sexual assault awareness month ended Wednesday.

But for many survivors at UCLA, the struggle to move on is constant.

Universities nationwide are facing a wave of official complaints from sexual assault survivors who allege their schools violated federal law by discouraging them from reporting assaults, underreporting assault statistics and mishandling their cases.

UCLA is one of the only major universities in California that has not recently received a federal Title IX complaint.

Title IX, one of the 1972 Education Amendments, requires schools that receive federal financial assistance to treat students equitably regardless of sex, including taking necessary steps to prevent sexual assault on their campuses, and to respond promptly and effectively when an assault is reported.

The last time UCLA resolved a Title IX complaint was in April 2001, and the case was about gender equity and athletics, said UCLA Title IX Officer Pamela Thomason.

Thomason said there have been no Title IX complaints filed against UCLA regarding sexual assault policies and procedures since she assumed her role in 2000.

More recently, students at the University of Southern California filed a Title IX complaint in May 2013. The U.S. Department of Education is currently investigating the complaint, as well as an allegation that the school violated the Clery Act – a federal law that mandates accurate and timely reporting of sexual violence, as well as other crimes, on or near a campus.

Students and faculty at Occidental College in Los Angeles also recently lodged Title IX complaints against the school. And at UCLA’s sister school in the San Francisco Bay Area, 31 current and former students at UC Berkeley filed a Title IX complaint in February.

The California State Auditor’s office is currently reviewing the sexual assault policies of UCLA, UC Berkeley, Cal State Chico and San Diego State University to ensure Title IX compliance and search for areas of improvement.

Officials in the California State Auditor’s office did not specify why they chose these schools, but they said the results of the audit are expected to be published in June.

Even as students continue to lodge federal complaints, many universities have been reluctant to admit any wrongdoing.

“Right now, there is a collective action problem among universities, meaning that no one university is going to step up and take ownership of the sexual assault problem and say they mishandled some cases,” said Annie Clark, a University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill graduate who filed a Title IX complaint against her university in January 2013.

Clark is one of the co-founders of “End Rape On Campus,” an organization that provides support for students filing Title IX and Clery Act complaints.

Clark said she believes many universities are currently looking for “checkboxes” to ensure they are compliant with federal law.

“In terms of technical policies, I can understand why there is a lot of confusion about (what to do),” Clark said. “I think they should ask ‘What do our survivors need?’ ‘What do our students need?’ and take a step beyond compliance with federal law.”

On Tuesday, the White House released its first sexual assault task force report with recommendations to “protect students from sexual assault.” UCLA already follows some recommendations – for example, the school created the position of victim-advocate three years ago and implemented a comprehensive sexual misconduct policy this spring.

One of the recommendations in the report is to conduct a climate survey specifically evaluating student opinions about the prevalence of sexual assault on campus.

After almost a year of surveying survivors’ experiences and relaying their concerns to university officials, Undergraduate Students Association Council Student Wellness Commissioner Savannah Badalich describes UCLA’s current approach to dealing with sexual violence and harassment as that of mere “compliance.”

“Most schools are at compliance. If you think of the responses to (complaints about how universities handle sexual assault) as floors of a house, some schools are in the basement. (Federal laws such as) the Clery Act, Title IX and, more recently, the Campus Save Act, raised a lot of schools to ground level. But I want UCLA to be in the attic,” said Badalich, who is a survivor of sexual assault.

Last fall, Badalich spearheaded the formation of 7000 in Solidarity, a student-run campaign that focuses on sexual assault education, advocacy and research among UCLA students.

A January report issued by the White House Sexual Assault Task Force highlighted sexual assault statistics specific to the college setting, including that one in five women experience sexual violence while in college. Another study cited in an April White House Task Force report found that about 6 percent of college males were survivors of either attempted or completed sexual assault.

Badalich said she believes UCLA has the potential to stand at the forefront of a revolution in how U.S. universities treat student survivors. But first, she said, UCLA needs to start including survivors in conversations about changing assault policies.

Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Janina Montero said the university and survivor groups such as 7000 in Solidarity share a common commitment to having a campus free from sexual violence.

She mentioned that UCLA nominated 7000 in Solidarity for a UC-wide award, and funded Badalich’s trip to a conference on sexual assault at the University of Virginia.

“We are as intentionally as possible, and as often as we can, putting the organization in the limelight and at the center of the conversation,” Montero said.

Problems with reporting sexual assault on campus

Prevention programs are a primary concern, university officials said, but they are also trying to create an environment where students feel comfortable reporting their assaults.

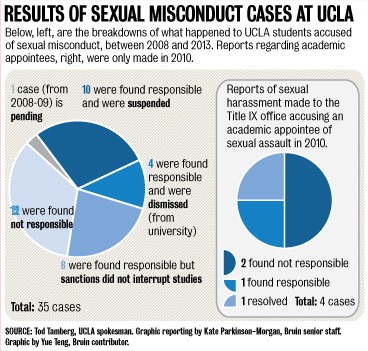

Multiple UCLA officials point to UCLA’s high number of sexual assault reports as evidence of a safe reporting environment. Among California universities, UCLA has the highest number of reported forcible rapes – 14 took place in 2012, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The second-highest number, 11, is at San Diego State University.

Montero said she believes the relatively high number of reports indicates that survivors feel more comfortable reporting at UCLA than at other universities.

Elizabeth Gong-Guy, director of UCLA Counseling and Psychological Services, has worked at CAPS for 25 years and said she notices more students coming to the counseling center to talk about “unwanted sexual encounters” every year.

“Years ago, these reports were so rare, and it’s not because assault wasn’t happening, it’s because there was a culture of silence,” Gong-Guy said. “We’re doing a better job now.”

Still, most sexual assault survivors do not report experiences with sexual violence to any legal or university authority.

While Badalich agrees high numbers are a good sign, she thinks the number of reports of sexual violence should logically be much higher than 14 a year, especially at a large public university such as UCLA.

“That shows we still have a reporting environment in which survivors do not feel like they will be heard or believed,” Badalich said.

Although there are currently no UCLA-specific statistics, the April White House Task Force Report cites statistics that only 2 percent of incapacitated sexual assault survivors, and 13 percent of forcible rape survivors, report the crime to campus or local law enforcement.

Survivors’ reasons for not reporting are varied and deeply personal, but according to the White House report many may be hesitant to call the encounter “rape,” because of the stigma attached to the identity of “rape victim.” Some said they also experience crippling guilt and self-blame after the assault, especially if there was alcohol involved.

Many survivors also know their assailant, and fear retaliation or isolation by the assailant or mutual friends of the assailant if they are in the same peer group. The National Institute of Justice reports that at least 80 percent of sexual assault perpetrators are an acquaintance of the survivor. Another report found that 40 percent of college survivors feared reprisal by the perpetrator.

In 2011, UCLA established the position of Campus Assault and Resource Education manager/advocate to share resources with survivors and help them navigate university and criminal procedures, Montero said. Currently, there are two full-time CARE manager/advocates – one of whom was recently hired – and another who works part-time.

Montero and multiple other UCLA officials said they noticed an increase in reporting after UCLA created the position in 2011. The 2011 Clery report indicates there were 13 reports of forcible rapes at UCLA compared to 10 in 2010. The number of forcible rape reports dropped to six in 2012, however.

Badalich said she thinks UCLA could improve its sexual assault resource outreach by hiring another full-time staff member to focus specifically on ensuring students know about survivor resources. The problem is not that the resources do not exist, she said, but that no one knows about them, and students need to be aware of the resources well before any sexual violence occurs. She would also like to see the university strategize more lasting, permanent ways to publicize resources, such as a creating a list of mental health and sexual violence resources to post in every bathroom on campus.

Bringing attention to sexual assault resources

UCLA recently released a video through its Title IX office to bring attention to on-campus resources for survivors of sexual assault. The video features current and former UCLA students reading a composite of accounts from real sexual assault stories. The university is also displaying several new informational screens about sexual assault resources and Title IX rights on monitors on campus and the Hill.

Thomason pushed for the creation of the video, but did not consult survivor advocacy groups on campus such as the CARE Speak Out and Support Coalition, 7000 in Solidarity and the Clothesline Project, in crafting the message of the video.

Although she did not consult with survivors, Thomason said she pays attention to what on-campus survivor groups are saying, and is impressed with their work. She said she is willing to consider feedback in future projects, but does not intend to release more ads or videos anytime soon.

Badalich never reported her sexual assault to university police or administration. Her assailant worked alongside her in student government, and she said she feared no one would believe her if she accused him of assault. For support, she contacted the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, the nation’s largest sexual violence institution.

She said she did not know UCLA provides counseling for survivors of sexual violence and survivor group therapy or that there was a Rape Treatment Center in Santa Monica.

Badalich came out as a sexual assault survivor to the Daily Bruin in September. Afterward, she started to receive dozens of text messages, phone calls and emails from students sharing their experiences with sexual assault at UCLA.

“Instead of making (the campaign) about educating students about sexual violence, it became students teaching us about what went wrong,” Badalich said.

Badalich has since realized that changing attitudes toward sexual assault requires more than educational programs. It demands attention to policy and power structures at the university level.

She said she and her campaign managers heard many stories of university police using insensitive, victim-blaming language with survivors, and discouraging them from making official reports. So Badalich met with university police in winter 2013 to talk with officers about how certain language could negatively affect the mental well-being of survivors and make them feel powerless in the reporting process.

CARE at CAPS representatives also facilitated a conversation with members of the police force in March about how language can perpetuate victim-blaming and rape myths, said university police spokeswoman Nancy Greenstein.

Representatives of CARE at CAPS also present at prevention trainings during student orientations and to “high-risk” groups such as incoming freshmen and the Greek community.

UCLA faculty are required to take two hours of sexual harassment prevention training – either through a computer class or in person – every two years, Thomason said.

Under the Violence Against Women Act, authorized in spring 2013, UCLA is also required to offer sexual assault awareness training for faculty. Thomason said the university incorporated that training into the sexual harassment prevention training for faculty.

Many survivors said they think UCLA should require more frequent, mandatory face-to-face student and faculty trainings, since the university currently only requires students to attend a training during orientation.

But trainings can only do so much, Gong-Guy said.

“Changing the culture is much harder to do,” Gong-Guy said. “It’s students engaging with other students that is much more likely to have an ongoing and powerful impact.”

One difficulty student advocacy groups face is finding sufficient funding for their efforts, Badalich said.

Debra Geller, executive director of community standards, said the university supports the campaign, and frequently informs Badalich of grants and funding, but that the administration cannot single out a specific student organization for an institutional budget.

“We don’t want to take over the program; we want it to be a student program,” Geller said.

Institutionalizing a response to college sexual assault

Badalich said she would also like to see an official sexual assault task force on campus. The task force could encompass CARE, CAPS, Student Legal Services, university police, survivor advocacy groups and survivors themselves.

She said she worries that unless there is a institutional university-wide group to address gaps in survivor resources, the focus on survivors will lose steam after media attention on the campus sexual assault problem wanes and students leading survivor advocacy groups graduate from the university.

“That’s all we talk about in the survivor network, that we’re being termed out, appeased until we graduate,” Badalich said. “We worry that this new wave of sexual violence awareness is going to end with very little.”

Montero said the university currently handles campus issues concerning sexual assault as they arise on a case-by-case basis.

The Safe Campus Committee, formed in May 2013, is the main administrative body tasked with determining best practices concerning UCLA sexual assault cases, according to Thomason. The Committee includes representatives from CAPS, Student Legal Services, university police, the Office of the Dean of Students, Office of Residential Life, Student Affairs, the Title IX Officer and a CARE at CAPS manager/advocate.

Thomason said she believes the CARE manager/advocate acts as a representative for survivors on the committee, but would be open to the idea of including a student representative. Badalich attended a few committee meetings, but is not an official student representative.

“The issue in including a student representative is if we have an advocate for survivors, do we need to have an advocate for an accused person? We want to be able to talk about and critically examine these issues,” Thomason said. “If there are survivors there without people with other perspectives, there’s a risk that we will act unfairly.”

But survivors said addressing these issues requires more than just a conversation between survivor advocates and university officials. Badalich and other survivors said university administrators, police and counselors need to start incorporating survivor feedback into long-term, institutionalized policy change to increase access to and awareness of resources.

Over the past few months, six student survivors of sexual assault sat down to speak to the Daily Bruin to talk about why they did not feel comfortable enough to report their assaults to university officials, or, in the few cases where the survivors reported an assault, how they felt university officials mishandled their case.

Almost all survivors said their university peers failed to provide a safe and supportive environment where they felt comfortable reporting sexual assaults. When many survivors told friends about their sexual assaults, they said their friends did not believe them and blamed them for the assault. The survivors who spoke to the police said officers’ emphasis on the difficulty of the reporting process often discouraged them from filing official police reports. A few survivors who met with university counselors said they were not made aware of their right to academic accommodations and access to sexual assault resources on or near campus.

Thomason said she and other university officials encourage feedback from survivors about these concerns.

“Whether there’s been a complaint filed against us or not, we want to make sure what we do is the best,” Thomason said. “We want to have good practices that encourage survivors to report, so that we can take the disciplinary actions that could help change the culture.”

For now, however, Badalich said she feels she is the primary point of contact for relaying student survivor concerns to university officials. She said she is now seeing changes and responsiveness from the university, but feels physically exhausted after a year of campaigning. For the first time in almost a year, she is attending counseling sessions to help her cope with recurring nightmares triggered by the stories she hears from student survivors. She was also recently diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I’m not saying I don’t love the work I do, but I’m the most miserable I’ve ever been,” Badalich said. “I’m both extremely excited by the change that’s come but I’ve been miserable just because of the sheer amount of work I have to do and the urgency I feel to do it all.”

Of the six survivors who spoke to the Daily Bruin, five requested anonymity. They said they feared stigmatization, blame and retaliation from university peers and administrators for speaking out.

Many survivors said that as much as they want to forget their assault, they want people at the university to remember.

Many said they did not think university peers or officials intended to treat them badly, but pointed to a widespread, societal lack of understanding of how to speak with people who experience trauma such as rape.

It was the momentary slips – slips of tongue, evidence that never got collected, that they said left them feeling neglected and alone. Words matter, they said.

For months after their assaults, many survivors suffered mental health issues. Former ‘A’ students stopped attending classes. Others contemplated suicide. Some did not graduate.

Their stories shed light on some of the gaps in university care for student sexual assault survivors, where there is more work to be done.

As one survivor who spoke with the Daily Bruin explained: “As a minimum, we should repair what we can, what’s already happened. While the goal is always prevention, we do have a culture of rape on campus. Sexual assault won’t stop happening, and we have to be prepared to deal with the aftermath.”

With contributing reports from Sam Hoff, Bruin reporter

It’s weird to read an article and wonder if you are being included in a statistic. In 2012/2013, I reported my assault to a campus official, who put me in touch with CARE and CAPS. I got a lot of help as a result, though I was never confident enough (nor emotionally prepared) to try to file charges.

I believe that the resources are out there and available (though I guess in some cases, a little research might be needed), though they could be more publicized. Articles like this are a good start.