Drive about 20 miles east of San Jose, Calif., wind through the isolated foothills until you reach the University of California’s Lick Observatory on Mt. Hamilton.

The once bustling mountain center is now noticeably empty, with only a handful of scientists and administrators scattered across the property.

The community on the mountain has shrunk as a result of UC budget decreases and now faces a total loss of UC financial support starting in 2018. In the event that not enough funding is found elsewhere to continue to operate the observatory, the telescope domes may only have each other for company.

***

Lick Observatory opened for operation in 1888, two decades after the UC’s founding. The University’s first observatory was funded by a donation from James Lick, a wealthy real estate owner in San Francisco. Lick’s telescope was the most powerful in the world when it was built.

Fifteen full-time staffers currently live on the mountain and keep the facility running, including supporting astronomers, technicians, mechanics, an administrator and one visitor center and gift shop cashier. They work every day that weather allows except for Christmas Eve and Christmas Day.

There are nine telescopes on Mt. Hamilton, five of which are used for research. Two are retired and two are only used for educational purposes, said Elinor Gates, support astronomer at Lick.

The newest telescope is the Automated Planet Finder, commissioned in 2012 to find planets around stars. The Katzman Automatic Imaging Telescope, painted in bright UC Berkeley colors, identifies supernovae and in the past has contributed to Nobel Prize-winning research.

Lick Observatory was also the first facility to measure the distance from Earth to the moon.

“We’re good at firsts here,” Gates said.

***

A tour around the Lick facility reveals a pattern of tangible changes resulting from multiple funding cuts in recent years.

Lick’s Crocker Dome, which once housed a prototype for the Kepler space telescope, now sits empty and is available for lease, Gates said.

A patrol car parked along the road to the observatory is rarely driven. The officer who once patrolled the area was recalled by UC Santa Cruz because officials deemed it an unnecessary cost, Gates said.

Gates added that, because more researchers are viewing results from their telescopes over the Internet, fewer astronomers visit the mountain. As a result, full-time cooks were no longer cost-effective, and now the dining hall is only used when staff decide to cook their meals there.

The Lick community was especially affected when the one-room K-8 schoolhouse closed about eight years ago. Gates said the nearby Alum Rock Union Elementary School District decided the schoolhouse teacher would be better utilized directing a full classroom of students in town rather than the 10 students on the mountain.

“It really sort of destroyed the community when they closed the school,” Gates said.

Over the past three years, staff levels at Mt. Hamilton have been reduced by 30 percent, said Kostas Chloros, superintendent at Lick. Even now, with 15 full-time staffers, the crew is short three positions, including the job of telescope mechanic.

It is hard for Chloros to hire people to fill these positions. Because it is uncertain whether new employees will meet the five-year requirement to secure employee benefits, not many people have said they want to work at Lick.

A telescope technician/mechanic hired late last year quit within two months, Chloros said. He added that the former worker’s main concern was uncertainty regarding his security as a UC employee.

***

The UC Office of the President said last year it does not plan to provide any systemwide funds for Lick Observatory after 2018.

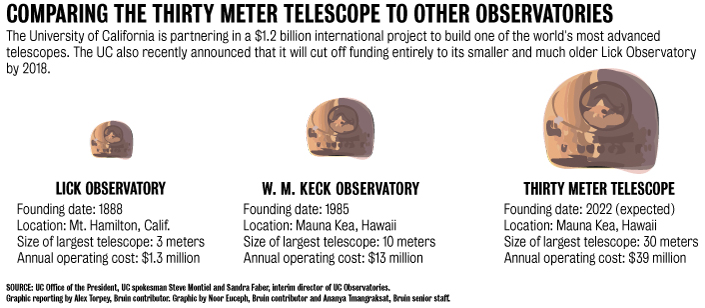

The UC is currently paying $1.3 million a year to support Lick Observatory through the 2016 fiscal year, said Sandra Faber, interim director of UC Observatories, an umbrella body that manages systemwide research and funds for astronomy.

For five years, the UC has not increased Lick Observatory’s budget at the recommendation of several reports, including one from the UC Observatories Board.

The UC Observatories Board told the UC Office of the President that alternative revenue for Lick would allow the University to concentrate resources on newer facilities, said University spokesman Steve Montiel. These include the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii as well as a new $1.2 billion plan to build a new Thirty Meter Telescope.

The question of how Lick should be funded in the future is a topic of debate in the astronomy community, andis emblematic of larger changes toastronomy research at the UC.

“Not every one agrees. There will be controversy,” said Steven Beckwith, UC vice president for research and graduate studies. “I believe our job is to make sure that any decisions are as broadly informed by the people involved.”

Recent declines in state funding and shrinking federal funding from organizations like NASA and the National Science Foundation have contributed to the strain on the UC budget for astronomy research, said Robert Kibrick, retired research astronomer at the UC Observatories and member of the Lick Observatory Council.

“There is a horrible budget problem now (at UC Observatories) going forward,” Faber said.

***

The Office of the President is conducting a study to evaluate how best to repurpose and fund Lick in the future.

“(The UC’s goal is) that the (observatory’s) historic value be maintained,” Montiel said. “(And) that there be continued educational and research opportunities available to the UC astronomy and astrophysics community and that the public outreach capabilities be improved.”

But some argue Lick should continue to be a facility for UC research.

The financial uncertainty spurred the formation of the Lick Observatory Council, which oversees the fundraising group Friends of Lick Observatory, said Alexei Filippenko, a professor at UC Berkeley who worked with the observatory.

But the search for alternative funding has been complicated by several factors.

“A lot of us have technology background, but none of us are professional fundraisers,” Kibrick said.

He added that the council is reaching out to other entities, like the Tech Museum of Innovation in San Jose, research institutions and individuals in Silicon Valley who might be interested in buying observing time.

But without the promise of matching funds from the UC, potential partners and donors may not be interested in Lick as a viable and stable place to do research, Kibrick said. He added that matching funds are typical expectations for most research investments.

One current donor recently decided to significantly decrease planned posthumous donations to Lick because of uncertainty about whether the observatory would still be operational when it receives the money, Kibrick said.

Also, if another organization interested in using Lick for its own research takes over the observatory, there is no guarantee that UC faculty and students would still be able to use it, Chloros said.

Sixty percent of principal investigators at Lick are graduate students and post-doctoral researchers, Faber said. But only faculty are allowed to apply for time at other telescopes, she added.

Geoffrey Marcy, a professor of astronomy at UC Berkeley, said that if Lick becomes unavailable to UC graduate students, they could learn just as well at Keck Observatory, a newer UC-owned facility, by participating in projects their advisers apply for.

But that still does not mean Lick Observatory has no chances of staying open, Marcy said.

“We’re going to do whatever it takes, that’s for sure, to keep it open,” Marcy said. “I still feel an obligation to make sure that we are prioritizing properly and moving on.”

Contributing reports by Emily Liu, Bruin contributor.

I guess moving on is really the best way to go. Welcome the new.

This article omits a number of key facts:

1. Lick Observatory is

wholly owned and operated by UC but Keck Observatory and the TMT are

not. UC is only a part owner of Keck and TMT, and does not have

exclusive control of either facility.

2. Accordingly, UC

observers receive nearly 100% of the observing time on Lick’s five

research telescopes and only 38% of the time on the two Keck Telescopes.

The UC Office of the President states that UC will have only a 12.3%

share of the TMT.

3. During the 3-year period covering FY 2011,

12, and 13, UC observers were assigned over 1,988 nights of telescope

time on Lick’s Shane, Nickle, and CAT telescopes versus 676 nights of

time at Keck. If one includes the KAIT and APF telescopes at Lick, the

number of Lick nights for this period exceeds 3,000 nights.

4.

If the Lick telescopes become unavailable to UC observers, this will

result in a drastic loss of observing time for UC faculty, researchers,

post docs, graduate students, and undergraduates. It will greatly limit

the number and variety of research programs that can be supported.

5.

While some research programs require large telescopes like Keck and

TMT, many do not, and instead require large blocks of telescope time on

only moderate-sized telescopes. Such projects are not feasible at Keck

or the TMT, where observing time is scarce, but are perfectly suited to

Lick. If Lick closes, observing time at Keck will become even more

heavily oversubscribed than it is now.

6. According to the

article, an astronomy professor at UCB asserts that if Lick becomes

unavailable to UC graduate students, they could learn just as well at

Keck by participating in projects their advisers apply for, rather than

devising and conducting their own research programs. Both current and

former graduate students do not agree with that assertion, as explained

in letters which can be found here: http://www.ucolick.org/SaveLick/testimonials.html

7.

Lick’s major research telescopes can be (and are) operated remotely by

observers at all 8 UC campuses that have astrophysics programs plus

observers at two UC-managed labs (LBNL and LLNL). Thus, they support

hundreds of observers (faculty, researchers, post docs, graduate

students and undergraduates) throughout the UC system.

8. Lick

functions as the primary base for UC astronomy education and public

outreach efforts. About 35,000 visitors come to Lick each year.

For

more information about the critical role that Lick plays in UC’s

astronomy education and research programs, including as an accessible

testbed for new technologies deployed at Keck and under development for

the TMT, please see http://www.ucolick.org/SaveLick/

For information about how you can help Lick continue operating, please see:

http://www.ucolick.org/SaveLick/help_save_lick.html

Robert Kibrick

Research Astronomer (retired)

UCO/Lick Observatory

Firstly, I’d like to correct a few facts in the article:

Lick Observatory was the first to measure the distance to the Moon using the retro-reflectors deployed there by the Apollo 11 astronauts, making the most accurate measurement in the distance yet made.

The dining hall at the facility, while no longer having staff cooks, is used by both visiting astronomers and staff, as well as for special events such as VIP dinners, graduate student and teacher training workshops.

Keck Observatory is jointly operated by UC and CalTech, so UC astronomers only get a portion of the observing time on the telescope.

TMT is a multinational project and UC observers will get a smaller fraction of time on the telescope than at Keck Observatory.

Secondly, the article does not highlight the amazing amount of research and education that is supported by the approximately $1.3 million annual operating budget for the mountain top facility (which is a mere 7% of UC’s ground-based astronomy budget). Many unique science opportunities are available at Lick that are not available at Keck, for example:

Conducting programs that require large numbers of nights on the telescope, such as the Lick AGN Monitoring Program.

Testing novel, new instrumentation and technology, such as FIRST (Fibered Imager foR Single Telescope) and Shane Adaptive Optics.

Allowing undergraduate and graduate students to apply for time directly for their science experiments and gain practical, hands-on experience.

In short, Lick Observatory is a vital part of the UC astronomy system and supports both the research and education goals of the university in ways that are not possible at other UC facilities.

Elinor Gates and Robert Kibrick have aleady pointed out (below) the factual errors and omissions about Lick Observatory in the above article.

Regarding the comment from “epikvision”: Well, we DO “welcome the new.” But that is no reason to abandon the old when it serves an extremely useful purpose and is relatively inexpensive. In particular, if Lick were to close, the people who would most greatly suffer are the young: undergraduate students, graduate students, and postdoctoral scholars. My own research group at UC Berkeley, for example, now has about 15 undergraduates, most of whom are using Lick. I would have nearly zero undergraduates if I had access only to Keck and space-based telescopes.

I respectfully disagree with my colleague Geoff Marcy’s view (if he indeed expressed it; he isn’t directly quoted) that UC graduate students “could learn just as well at Keck Observatory.” They get far less access to Keck than to Lick, and they can’t be the leaders of Keck projects. Lick enables and encourages the development of strong, independent scientists, and it provides the opportunity to conduct long-term, risky projects. Professor Marcy himself greatly benefited from having extensive Lick access in the early days of the search for planets around other stars, as described by his former student Paul Butler at

http://www.ucolick.org/SaveLick/docs/testimonials/Butler_Letter.pdf .

And Marcy doesn’t address the fact that almost all UC astronomy undergraduates would be shut off from ground-based research if Lick were to close.

Lick Observatory is critical for students, the very people UC was designed to serve. The UC Office of the President should continue to provide core funding, and matching funds for private donations. With sufficient UC and external support, we can make Lick an even better facility for research, and education, and public outreach.

For more information, please read the Op-Ed (Filippenko et al.) and the Editorial in today’s issue (4/21/14) of The Daily Bruin.

Alex Filippenko

Professor of Astronomy

UC Berkeley