A walk through quiet corridors and past a wide grass field takes two UCLA graduate students, with 57 hand-picked books in hand, to an empty room in the Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall.

Inside, Xuemin Zhong and Linda Kobashigawa spread out the books on a wide recreation table and ask teens incarcerated in the facility to come up and choose what they want to read.

Some are hesitant while others are more eager. Many search for something they can relate to while others search for an adventure they can get lost in.

After about an hour, almost every boy has at least one book to call his own.

“We are not changing the institution, we’re not even sure if we’re improving their education, we just know that we’re providing an outlet from their monotonous schedules,” Zhong said.

Zhong and Kobashigawa, graduate library and information science students, are members of Books Beyond Bars, a UCLA student group that works to provide books and educational services to teenagers at Nidorf Hall, a juvenile detention center that houses 214 minors – 198 boys and 16 girls – about 20 miles away from UCLA in the San Fernando Valley.

The student group began in 2005 when Keren Goldberg, a UCLA alumna working for the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, requested help from UCLA to supplement the lack of reading opportunities at the facility.

The group and probation staff initially hoped to build an on-site library at Nidorf Hall, but a lack of funding and resources stopped them from continuing with the goal, Goldberg said.

Instead, Goldberg invited the UCLA students to work directly with teens at the hall through book talks and visits.

The student group started out strong almost a decade ago, making visits to Nidorf Hall about six times a week. But stricter security policies put in place by the hall about six years ago have made it harder for students to gain access to the facility and meet with the teens.

Zhong, president of Books Beyond Bars, and Kobashigawa, the group’s vice president, are currently the only two of its group members cleared to visit the teens, a process that takes six months. Because few students can make this commitment to volunteering, the group is only able to make one trip to the center per week, Kobashigawa said.

Few of the teens stay at the hall for long, making it harder for UCLA students to build lasting relationships with them. On average, the teen boys spend about 21 days at that location before being released or relocated to another facility, said David Evans, superintendent of Nidorf Hall.

In their most recent visit, a teenager told Zhong and Kobashigawa that it would not matter if they returned to Nidorf Hall again with more books, since he would probably never get to read them. He said he was going to county jail soon.

Nonetheless, Goldberg said she believes Books Beyond Bars is making a noticeable impact.

“For some of these young people, no one has given them a book or encouraged them to enjoy reading,” Goldberg said. “Mental health isn’t just about therapy but about the whole person.”

Before an on-site visit, Zhong and Kobashigawa pick the books they will take to minors at the facility from a library of books in the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies building. Zhong and Kobashigawa also purchase books from an Amazon wish list using grants from UCLA’s Community Activities Committee and some books are donated to Books Beyond Bars.

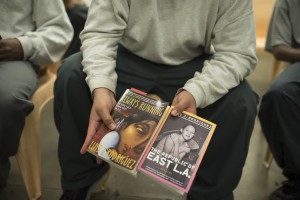

The books they select to take to the hall tend to favor novels that showcase inner-city life and related problems. Books such as “Lady Q: The Rise and Fall of a Latin Queen” and “Monster: The Autobiography of an L.A. Gang Member” are frequently requested by teens at Nidorf Hall, Zhong said.

When the two students reach the hall, security personnel search through each book to make sure no possible weapons – like hardcover books and staples – or inflammatory material get inside the facility.

Zhong and Kobashigawa said the guards’ filtering of the books often seems arbitrary to them. But Evans said he thinks prescreening is necessary to prevent material considered inappropriate for minors.

The rule keeps explicit material out but it also denies many requested books, like autobiographies by Stanley Williams that speak against gangs from the perspective a former gang leader. These autobiographies are sometimes rejected because they include unadulterated content and are considered inappropriate.

Some teens said they prefer autobiographies by former criminals who succeeded later in life.

”It shows how they had the courage to change,” one teenager said after choosing his books.

When the pair later returns to UCLA, they sometimes keep the rejected material in a box labeled “awesome but currently banned” filled with books like Williams’ autobiographies.

Every now and then, Zhong tries bringing some in, hoping they’ll get past the guards. Occasionally, one finds its way to a reader.

As the teenagers began to choose their own books, one boy stopped at a fantasy novel but then hesitated.

”I don’t know if I can read something like that,” he said.

Zhong stepped up and assured him he could, that a fantasy novel could be something he likes. She said there’s no harm in trying something new.

He walked away grinning, the book in his hand.