The original version of this article contained an error and has been changed. See the bottom of the article for additional information.

The conversation about growing class sizes at the University of California has become so persistent that it runs the risk of becoming a cliche.

Last month the UC Student-Workers Union, UAW Local 2865, which represents over 12,000 UC teaching assistants, readers and tutors, filed a complaint against the University with California’s Public Employment Relations Board for refusing to include class size in workers’ contract negotiations.

Earlier this week the union held its most recent set of bargaining meetings at UC Davis, where graduate students spoke about their experiences with large class sizes and tried to bring the issue to the table as a bargaining item.

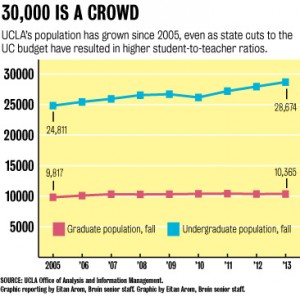

The teaching assistants’ concerns and complaints are not only valid, but come at a particularly important time for the University – between 2005 and 2011, the student-faculty ratio at the UC ballooned by over 10 percent.

But the union needs to realize that the University cannot necessarily promise certain class sizes to teaching assistants as part of their contracts. The issue is subject to a much larger set of budgetary considerations, many of which are addressed individually by each campus.

Because of this complexity, including class size as part of contract negotiations simply is not feasible. Doing so would likely reduce a complex issue to a set of demands the University might not be able to meet.

According to UC spokeswoman Dianne Klein, because each campus distributes its own budget allocations according to individual priorities, academic decisions like hiring faculty, expanding departments and controlling class size are all intertwined – making the issue particularly difficult to pinpoint and to address.

Nonetheless, this complexity and autonomy does not excuse the UC Office of the President from directly addressing the important complaints brought forth by the union.

Although the University cannot make any promises with regard to class sizes, it can promise to make the graduate student union an integral part of that conversation.

To properly address nuances and give this issue the attention it deserves, UC leaders need to let input from teaching assistants influence their agenda. By bringing the union into the conversation about class sizes, the University can gain a realistic perspective from the graduate students who experience the effects of budget cuts in the classroom.

Brandon Buchanan, a graduate student in sociology at UC Davis, said he has taught up to 60 students for some upper division courses. He added that having this heavy a workload makes it very difficult to grade papers, provide extensive feedback, answer emails and hold effective office hours.

This reality is all too familiar at UCLA, the UC campus with the highest population of undergraduates. According to a university report, in 2011 UCLA had a student-to-faculty ratio of about 20 to one, although that number does not factor in teaching assistants.

The fact that larger classes reduce individual student attention and thus quality of education is a given. In addition, large classes add another level of stress for teaching assistants who want to do their job effectively and responsibly.

Because they are students, teaching assistants can only legally work 20 hours per week. With larger class sizes, therefore, they work the same number of hours but cater to a larger set of students, undoubtedly leading to a decline in the academic experience from both the teaching assistant and student perspectives.

“I’m put in an untenable position,” Buchanan said. “It is possible to do my job in 20 hours (a week), but its quality is sometimes sharply decreased because I do not have the ability to spend quality time on my work.”

The University should not brush off this unfortunate reality, even if it does not fall within the scope of labor negotiations.

“Who wouldn’t be sympathetic to the plight of conscientious graduate students who want to do the best they can?” said Klein. “But it is not a problem you can fix in the bargaining process.”

At the end of the day, UCOP needs to do more than just sympathize. Instead, it must respond to graduate students’ demands by coming up with a constructive way to include them in a vital and ongoing conversation about class sizes.

Guaranteeing a voice for teaching assistants in budgetary decisions would not be conceding to labor demands. It would be serving the campus community in a more inclusive, proactive way.

Email Ferdman at mferdman@media.ucla.edu or tweet her @MaiaFerdman. Send general comments to opinion@media.ucla.edu or tweet us @DBOpinion.

Correction: Brandon Buchanan, a graduate student at UC Davis, said he taught up to 60 students for some upper division courses.