Wherever he goes, people stare inquisitively at Robart Page’s 7-foot frame and ask him the same thing – “You play basketball, right?”

The answer today is simply and unequivocally no.

Less than two years ago, however, the response to that question was significantly more complicated for the UCLA men’s volleyball’s senior outside hitter.

Page, considered the No. 1 high school recruit in his class by ESPN in 2010, had doubts about his volleyball future after a sophomore season marked by frustration and insufficient playing time.

(Austin Yu/Daily Bruin)

By spring 2012, as one door was in danger of closing, to Page’s surprise another door opened up. Page was presented with an offer that looked too good to pass up.

It was an offer to transfer, but not to another school to play volleyball. Page was offered the chance to switch to the UCLA men’s basketball team by former coach Ben Howland.

The second court

Page’s trouble started the summer after his freshman year.

After seeing significant time at outside hitter in his first year, Page received a call over the offseason from then-coach Al Scates. He wanted Page to switch from his more familiar role as an outside hitter to opposite – a position Page had never played.

Page struggled to adjust during the preseason, and Scates quickly pulled the plug on the experiment.

“We had two great middle blockers who were two of the best hitters in the country, but we could only go to those guys when the passes were really good,” Scates said. “When we could pass well, no one could beat us … Robart couldn’t pass well enough to let us go to the middle.”

Throughout his 50–year tenure as UCLA men’s volleyball head coach, Scates used a unique two-court system during practices. The top 14 or 15 players would train on the first court and suit up for games, while about 20 players would be relegated to the second court and not see playing time.

The second court would be monitored by a volunteer assistant who would report to Scates periodically about the progress of those players. When Scates decided Page wasn’t ready to play opposite hitter, he sent him down to the second court.

“You’re basically told you’re not good enough, and then there’s no timetable for when you’re going to get called back up,” Page said. “You’re working really hard but you don’t know if it even matters because none of the real coaches are even watching.”

That year the team won game after game – at one point winning 16 of 17 consecutive games – meaning there was little reason for Scates to mix things up.

Page was stranded on the second court and only played in three matches all season, a departure from the 22 games he played the season before.

“It’s a brutal mental battle, from playing a lot of matches my first year and having a solid ego to watching your team play in the stands,” Page said. “Scates was happy with what was happening on the first court so there was no need to make a change and bring me back.”

It’s hard to criticize a system that brought the university 19 national championships, but Page saw the two-court system as a liability to team chemistry.

“That system can work, and it worked for Scates for a really long time, but the problem is that it can really tear the team apart,” Page said. “Everyone’s just fighting for positions, you’re trying to beat someone out to get a spot and then you forget about what you’re trying to do as a team.”

It was a cutthroat culture, and an unlikely opportunity was about to offer Page a way out of it.

The offer

Shortly after the end of Page’s disappointing sophomore season, he ran into Howland at the Acosta Athletic Training Complex.

Howland invited Page to stop by his office for a chat, where Page vented to Howland about his building frustration with volleyball. Howland’s response took Page by surprise.

“He basically said he was having a lot of trouble with some of the big men on his team with grades, drug testing or eligibility-wise,” Page said. “He was short on numbers for the coming year … and he had heard or seen me play in some (Amateur Athletic Union) tournaments in high school.”

Page played basketball up until his senior year of high school, by which time he had already committed to UCLA volleyball. Although no offer had been made yet, the idea of playing basketball again intrigued Page.

A few days after the first talk, an informal “tryout” of sorts took place.

“One day I went in the gym to serve and pass with (senior outside hitter) Gonzalo (Quiroga) and Howland was in there working with Josh Smith,” Page said. “He says, ‘Hey Rob, come play some defense on Josh,’ and I was like ‘Alright, let’s do it.’”

It was a haphazard, out-of-nowhere chance for Page to show if he still had any basketball skills left after three years away from the game, this time stacking up against one of the men’s basketball team’s most high-profile players.

Page passed the test.

“I don’t know what I even did, I remember I got dunked on once or twice,” Page said. “I guess (Howland) was impressed with my defense though, because he told me they had a scholarship available for me to play basketball … I told him I was going to talk about it with my parents over the summer and see what they think.”

Page returned to Rochester, N.Y., and let his parents in on the situation. Before he knew it, word had spread around town that one of its own had been offered the chance to play basketball at UCLA.

It was an offer to be excited about, but not one to decide rashly upon. Page’s father knew there were many possibilities to consider.

“There was definitely that part of me who, as a guy who loves basketball, was thinking, ‘Wow maybe he should give this a shot,’” said William Page. “It certainly could have been a great lifetime experience, but it could’ve also been a one-and-done deal where he might burn his bridges with volleyball and then it all goes in the wrong direction.”

Page went over his options not only with his parents, but also with his volleyball teammates.

“I wanted him to make his own decision … I wanted him to be where his heart is, and if his heart wasn’t into volleyball I would have supported him going to basketball,” said senior middle blocker Spencer Rowe. “In order to give it everything you have to the team, you have to be all in.”

The “decision”

Basketball may have been an easy choice for Page if not for the arrival of John Speraw as the new UCLA men’s volleyball coach. At the end of the 2012 season, Scates retired after 50 legendary years at the helm, and Speraw was widely recognized as a replacement of the highest caliber.

“I’m in a position now where I can either play for the best college coach in the country, or I can go play basketball,” Page said. “It was just one of those things where you have this opportunity and you’re like, ‘Wow can I really pass this up, playing basketball for UCLA?’”

Page decided to give his new coach a call and ask for advice.

Speraw recognized that the opportunity of playing basketball for UCLA was huge, but also said Page would have a chance to be a key part of the volleyball program should he decide to stay on.

“I for sure understood that he wasn’t pleased with the way his career had gone so far and I knew he wanted more out of it,” Speraw said. “I wanted to coach him … I was pretty convinced he could reach his goals if he worked hard.”

Ultimately, the decision wasn’t left up to Page – the decision was made for him.

As the summer wound down, Howland and UCLA Athletic Director Dan Guerrero began working out the logistics of the transfer in case Page ultimately decided to pursue basketball. That’s where things began to break down.

“I was still 100 percent considering basketball, but Howland basically said it was going to come across as if I was being stolen or something,” Page said. “I think I would have needed to be the one to initially go to (Howland) and say I was done playing volleyball … I also think at that time Howland was walking on some pretty thin ice.”

It wasn’t exactly Page’s decision, but it turned out to be the right one, he said. Page called Speraw right after the logistics of the basketball transfer fizzled out to let him know he was all in for volleyball.

The result

Once Speraw took over, he instantly inserted Page into the starting lineup and allowed him to develop in his natural position at outside hitter. An offensive system was put in place that played to Page’s strengths, and the two-court system was done away with.

Page’s game improved exponentially as he settled in to Speraw’s playing style.

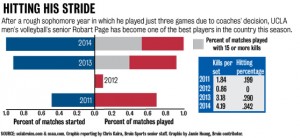

By the end of his junior year Page established himself as one of the best players on the team, and the growth didn’t stop there. Page kept his momentum on the court going into his senior year; he is currently leading the team in kills and is in contention for AVCA National Player of the Year.

It took some time for Page to finally live up to the hype of his No. 1 recruit status, but Speraw knows that all successful players face a degree of adversity.

“Everyone’s journey through collegiate athletics is never smooth, there are challenges along everybody’s path,” Speraw said. “The ones that end up on top are usually the ones that work through those challenges and become better people.”

Page might have taken a different path if he possessed full control of the decision. But in the end, it doesn’t matter.

“I’m really happy basketball didn’t work out to be honest, the main reason I was considering it was just because of how frustrated I was the year before,” Page said. “Basketball seemed great for a second, but I’ve realized volleyball is what I love.”

Page will have to continue to put up with strangers approaching him to ask if he plays basketball. That question comes with being 7 feet tall.

Some will give Page a puzzled look when he answers no, but he couldn’t care less. He’s a volleyball player from head to toe, and that’s a long way down.