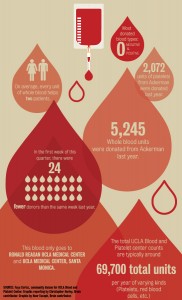

Officials at the UCLA Blood and Platelet Center have seen fewer donations than usual this quarter.

There were 24 fewer donors at the center’s Ackerman location in the first week of winter quarter compared to this time last year, said Faye Cortez, community liaison for the center.

“While it might not seem like much, when you consider that each donation typically helps out two patients, it adds up quickly,” Cortez said.

The Blood and Platelet Center donates exclusively to the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center and UCLA Medical Center, Santa Monica, said Linda Goss, blood donor recruitment supervisor for the center.

The center’s donations account for about 82 percent of the hospitals’ need for blood products, which include red blood cells, platelets and plasma, said both Cortez and Goss.

Goss said she attributes the decline to a number of reasons, primarily problems with the implementation of a new computer system for donations.

Fernando Gironas, operations coordinator at the Ackerman site, said he also thinks the primary donors for some time – baby boomers – are not donating as much.

He added that, in some cases, the baby boomers are also starting to become recipients themselves, which may contribute to the decline.

The center is trying to counteract the general decrease with outreach, having more blood drives around campus and providing free snacks and drinks for donors, Gironas said.

Any difference between supply and need has to be bought from other blood banks, Goss said.

Although many donations are given at either of the center’s fixed locations in Ackerman and on Gayley Avenue, most of them come through the mobile sites the center offers throughout the year on UCLA’s campus or at local high schools, Goss said.

Platelets, on the other hand, are collected only by the static sites on Gayley and in Ackerman, and then get sent to the two UCLA hospitals, Gironas said.

The Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center is one of the few trauma centers in the area, so patients who arrive there often need more blood than usual, Gironas said.

For example, during the Santa Monica College and Los Angeles International Airport shootings over the past year, victims were brought to Ronald Reagan, prompting calls by the hospital at the time for additional donors to help the victims and replenish diminished supplies.

The many specialty clinics in and around Ronald Reagan typically require more blood than average primary care locations, Gironas said.

The sites are getting a majority of their donations through repeat donors, he said.

Gironas said one repeat donor, Andrew Sincuir, a third-year anthropology student, is one of his “student heroes.”

Sincuir’s brother, a UCLA alumnus, told him to donate blood for the first time while still in high school, and Sincuir said he continued when he came to UCLA, making his first donation his first week as a student.

One week, he said he decided to try donating platelets, which takes about double the time of a normal donation.

A week later, he received a call telling him that a patient reacted really well to his platelets and asked if he could make another platelet donation.

“I just figured ‘OK, I can do this,’” Sincuir said.

Now, with few exceptions, he comes back every two weeks – the minimum time required between platelet donations. Sincuir has donated almost four gallons of blood products over the last three years and has no plans of quitting.

Even if they were donors in high school, not all students continue to donate once they are at college.

Rubin Hsu, a fifth-year aerospace engineering student, said he often donated in high school since his friend was in the hospital at the time.

But he said he does not feel as comfortable donating without a connection to the people who might be receiving his blood.

Hsu said he didn’t know about the incentives offered to donors, such as free movie tickets or Ackerman food vouchers, and while they may have motivated him, had he known, he said he still probably wouldn’t have.

“Because then doing it isn’t about donating anymore, it’s about the prize at the end, which isn’t what I think it should be,” Hsu said.

While both Cortez and Gironas emphasized the demand for Type O-negative – also known as the universal blood type – both said all blood types are wanted and needed.

“Each day brings different variables and situations, and it makes it hard to predict the need for any particular type,” Gironas said.

Even some students from the school across town find themselves donating at Ackerman.

UCLA alumnus Matthew Gercler, currently a graduate student at the University of Southern California, said he started donating as a second-year at UCLA and continues to come back on campus just to donate.

Sometimes, however, even when there’s the will to donate, the center has to turn down donors for a variety of reasons, from living abroad to certain diseases.

Luke Sonnet, a graduate student in political science, said he contracted malaria as a child while living in Morocco, and therefore isn’t allowed to donate according to American rules governing blood donations.

Because the hospitals need an average of about 100 blood units per day, the center is always seeking more donors, Cortez said.

“Even when we’re doing well, we could always use more blood,” she said.