A year ago, Madeline Brooks would have been in warmups on the bench cheering on her teammates.

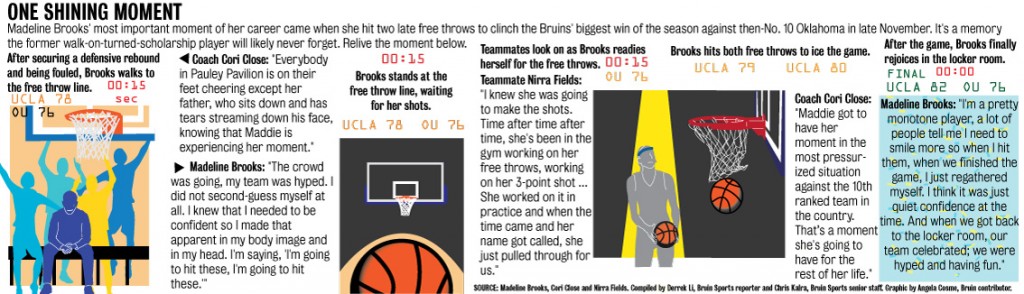

But this season against then-No. 10 Oklahoma, the junior guard found herself walking the almost 80 feet from the defensive baseline to the free throw line with UCLA up two points and 15 seconds left on the game clock.

Under the bright lights, all eyes in Pauley Pavilion followed Brooks’ footsteps.

Brooks said she made sure that her body language reflected her steeled confidence the entire way. She kept telling herself that she was going to hit those two free throws.

In an eerily silent Pauley Pavilion, the bounce of the ball reverberated through the stadium, followed by a swish. The crowd exploded briefly before it hushed itself to watch the second follow suit.

(Erin Ng/Daily Bruin senior staff)

And just like that, Brooks pushed the Bruins’ lead to four, slamming the door on the Sooners’ hopes of avoiding an upset.

“Maddie got to have her moment in the most pressurized situation against the 10th-ranked team in the country,” said coach Cori Close. “That’s a moment she’s going to have for the rest of her life.”

But more than three years ago, no one could have foreseen Brooks having such an opportunity.

As a high school junior, Brooks received interest from many schools before she went to a Christian camp at the beginning of summer. There, she face-planted after trying to pull a 360 on a wakeboard pulled by a speedboat. Brooks got a concussion, but didn’t tell anyone.

For an entire summer during the recruiting process, Brooks played with the concussion in front of the watching eyes of schools and coaches.

“You can imagine having a concussion; you’re off balance, you’re seeing different things at times,” said her father Steve Brooks. “The coaches watching are thinking she’s not very good, so a lot of interest fell off.”

After being cleared the beginning of her senior season, stress fractures in her knee and ankle took her out for most of her games.

While some smaller schools were still interested, Brooks always wanted to go to a bigger school, and therefore chose the school her mother and older sister had attended: UCLA.

Although she wasn’t recruited by UCLA, Brooks walked into Close’s office with a list of reasons why Close should let her walk on to the UCLA women’s basketball team.

After convincing Close she could contribute to the team on the court and off, Brooks saw her minutes on the court limited to mostly ends of blowout games.

“In my first two years here, especially my first year, I took a lot of mental reps,” Brooks said. “I watched the big guards make the plays, shoot well and do the right things on the court.”

While relegated to mostly watching games and only taking half the reps in practice, Brooks said she trained herself to be always ready mentally.

Physically, she puts in the extra work to match the mental preparation.

“She has worked very hard,” Steve Brooks said. “She spends a lot of endless hours in the gym shooting and working on different aspects of the game, unbeknownst to I think a lot of people.”

But teammates and coaches did notice her growth and selflessness, seeing how Brooks cared more for the team than for herself.

At the end of her second year as a walk-on player, Close had Brooks give a speech at the end-of-the-season banquet, explaining why the word “uncommon” so perfectly described the goal of the team.

Then, in front of the team and the players’ families, Close stood up with a surprise that she had been painfully keeping secret for the last two months.

“You described exactly what it means to be uncommon in this program, Maddie,” Close said. “To be an uncommon woman, making uncommon choices, and in this case, yielding an uncommon result to earn a full scholarship to UCLA.”

The guard who walked on to the UCLA women’s basketball team had not only just been awarded the uncommon award, but had also earned a scholarship.

Upon hearing the news, the crowd at the banquet just erupted.

“People were on their feet immediately, tears falling,” Close said. “It was one of my favorite moments of all last year, to be able to honor her that way and to see the response that everybody had.”

While not usually one to show emotions, Brooks broke down and cried in front of the standing ovation.

“I’m just really thankful for the opportunity to be rewarded in that way because coming in, I didn’t want to be rewarded,” Brooks said. “I expected to pay the price and be a walk-on my four years here; I wasn’t coming in with a scholarship expectation.”

This season, Brooks has had to take on a bigger role than expected after injuries have forced the Bruins to play only seven players most games.

That means she finds herself in key situations on a regular basis, a startling change from the first two seasons of her collegiate career.

Brooks said getting every single rep in practice instead of being in every other rotation has given her more confidence during games, a sentiment echoed by senior guard Thea Lemberger.

“I think it’s a little bit experience and then a little bit confidence,” Lemberger said about the biggest change she’s seen in Brooks. “Just feeling more comfortable out there, believing that she has the skills and abilities to contribute to the team and being confident in that.”

For two seasons, Brooks had to watch her teammates thrive on the court, but she always kept one eye on the clock and stayed ready for anything.

“It’s my hard work and competitive nature that’s let me get here,” Brooks said. “I willed myself here, I worked hard to get here, and then I’ve been rewarded. It’s not like a golden ticket that’s just been handed to me.”

While she wasn’t handed a golden ticket, Brooks was handed a basketball. With it, she stepped up to the line in UCLA home whites and delivered.