It was 4:30 in the morning and Joanna Cooper and her fellow UCLA students were fast asleep on the fifth floor of Rieber Hall. The weather was windy. A mild earthquake had actually occurred a week before.

Suddenly, the buildings started shaking violently. There were loud noises, people were screaming and it was pitch black as students ran toward the stairwell. Emergency lights flashed. Firetrucks rushed to make sure no one was trapped inside.

“It really felt like we were rolling,” said Cooper, who was a second-year student at the time.

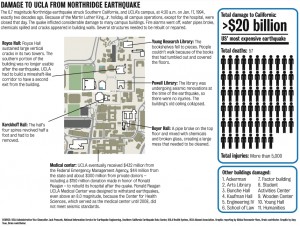

On Jan. 17, 1994, a 6.7 earthquake hit the city of Northridge, killing 57 people in Los Angeles and causing about $20 billion in damage. It was the most costly earthquake in U.S. history.

Thursday afternoon, nearly 600 people, from politicians to engineers, gathered for a symposium at UCLA with one goal: preventing the damage that would accompany another Northridge earthquake.

Speakers and other experts said the Northridge earthquake showed how seismically unprepared California was and how out of date many of its buildings were at the time.

In the past, many authorities did not think their structures would have to handle such a large earthquake,said Jian Zhang, a civil and environmental engineering professor at UCLA.

The earthquake was a lot more damaging than expected, Zhang said.

At UCLA, the earthquake cost $120,000 in labor expenses to clean up debris. Millions more would later be needed to repair many of UCLA’s buildings, such as Powell Library, where the ceiling collapsed. Royce Hall had vertical cracks in both towers and the southern portion of the building was completely unusable.

Campus closed for almost a week after the quake to make repairs go faster, said Jack Powazek, then director of facilities and now administrative vice chancellor at UCLA.

“If (buildings) can withstand the earthquake, then people survive,” Chapman-Henderson said. “The local economy survives and the community survives.”

Because the earthquake occurred so early in the morning, injuries to UCLA students were minimal.

The campus had no electricity immediately following the quake even though it had just started operating a new co-generation plant a week before, Powazek said.

“It was so eerie. For the first time ever in Los Angeles, I could see all the stars,” said Matea Gold, who was a second-year UCLA student and Daily Bruin assistant news editor at the time.

After the students were permitted to re-enter the dorms they could not sleep. Students on the fifth floor of Rieber Hall stood in line in their resident assistant’s room to call their parents since it contained the only working phone.

The school rationed water for students, handing out bottles of water so that they could wash themselves and brush their teeth. There was no running water for two or three days, Cooper said.

UCLA’s dorms were built to reduce damage during an earthquake. In fact, buildings had rollers at the bottom of the floor that were designed for the building to better absorb the impact.

Older buildings without rollers and other safety measures suffered the most in the Northridge earthquake. Some of those buildings have been retrofitted, but other buildings still remain without some safety measures.

Many of the symposium attendees expressed concern that Los Angeles is still not adequately prepared for a large earthquake. Only 16 percent of county residents have earthquake insurance, a drop from 33 percent in 1994, according to the California Earthquake Authority.

They also discussed ways to prevent such damage in the future, including increasing the number of people who have earthquake insurance and advocating the use of more sound materials to construct earthquake-safe buildings.

Former governor Pete Wilson, who was in office at the time of the earthquake, said California’s dependence on technology means it cannot afford to have such an earthquake damage its power grid and needs to improve its earthquake preparedness.

Wilson added that the government needs to organize good communication planning and a central communication agency for a quick response to the earthquake and to prevent the spread of false rumors.

Wilson emphasized the need for the region’s residents to prepare for a large earthquake that is expected to hit Southern California soon.

“(The) first rule, obviously, is anticipate,” he said. “Know that it’s coming and undertake all you can in a preventive fashion so you minimize the damage.”

The Northridge symposium will continue today with numerous workshops on science and public policy.