At UCLA, 25-year-old nurse Paolo Montenegro often works 12-hour night shifts three days a week on the neurotrauma floor of the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center.

He takes care of people who have been shot, stabbed, fallen off their motorcycles, weakened from strokes and brain bleeds. Like all doctors and nurses, he was trained to look at his patients with professionalism and nonchalance.

Every case is sad, and caring emotionally about every patient would be draining and difficult, he said.

But in the Philippines, it was different. Unlike his patients at Ronald Reagan, who couldn’t talk because they had ventilators or were recovering from trauma, these patients in the Philippines talked to him normally and frequently and invited him into their homes.

Montenegro described his patients as poor with money and materials but rich in hospitality and gratitude. One woman he met had lost everything but her family, and she still wanted to give him and his colleagues mugs of Coke.

They told Montenegro about their lives. The family of 23 who lived under one roof. The woman whose house was only partially rebuilt by foreign volunteers but enough to shelter her from the winds. The mother who was pregnant when the typhoon hit and took away her family’s boat and fish.

“A lot of them just want to talk to somebody, they just want to vent, how they felt, how they’re feeling,” Montenegro said. “You just have to kind of tend to their needs as well. I guess the big part of it is just listening. It doesn’t seem like a big thing, listening, but it means a lot to them.”

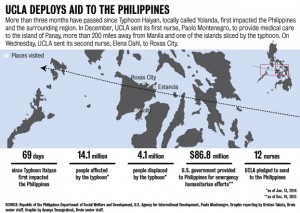

Montenegro was the first nurse UCLA sent to the Philippines to help with the relief effort after Typhoon Haiyan, locally called Yolanda, hit the region in early November. About three months have passed since the typhoon hit, and the Philippines and its struggles to rebuild have largely disappeared from the media and from international attention.

Montenegro went to volunteer in the rural in-between areas of the island of Panay, where the countryside is bright green and the houses are simple, made of bamboo. He volunteered in Estancia, a small municipality in the region of Iloilo still suffering from an oil spill caused by the typhoon. It is especially difficult for the people there, many of whom depend on fishing for their livelihood.

He and about 40 other medical personnel set up triage stations, where they diagnosed medical problems and directed patients to the medicine they needed. Most of the people he served were poor and lived off the land. He assessed babies two weeks old and elders as old as 90. Children with multicolored flip-flops and small hands, women with tired eyes who still smiled when company arrived.

Many of his patients suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. The typhoon had taken away not only homes, but restful nights and their peace of mind.

But most of the medical conditions Montenegro found were chronic, and his patients had had them for months or years before the typhoon, like high blood pressure, diabetes and asthma. Most of the residents have little regular access to health care, so such conditions were allowed to persist without proper attention. In terms of health care, every month the local government would send one medical worker to their village, but that was about it, Montenegro said.

“They’re already an underserved community, and I guess the typhoon kind of exacerbated that,” Montenegro said.

November’s typhoon battered a country not well-fit to withstand such damage, especially from an extraordinarily powerful storm like Typhoon Haiyan, said Donald Morisky, a UCLA public health professor who has spent decades researching HIV/AIDS in the Philippines.

Many houses in the country are not very stable and are made of poor materials, Morisky added. Philippine residents are still trying to reconstruct power lines, while fallen coconut trees and flattened houses remain scattered in the landscape, Montenegro said.

This is why National Nurses United, the union of which Montenegro is a member, still sends nurses to the Philippines, months after the country has disappeared from the front pages of U.S. newspapers.

“What happens a lot of times after these disasters … (is) there’s an immediate response of first responders and media, and then it very quickly fades, and yet the need is still there,” said Martha Wallner, spokeswoman for National Nurses United. “The need (was) still there even before the disaster.”

In the months after the storm, for the Philippine residents, family meant their neighbors too, and they would spend much of daylight outside at their town’s community centers, chatting and being satisfied with each other’s company. They had a lot taken away from them, so they stayed together, Montenegro said.

“There’s … just a lot of destruction. It’s very terrible,” Montenegro said. “But what surprises me is that even though the people in that area … regardless of how poor they are and the little they had was gone, they’re still pretty happy, they’re still very welcoming, they’re still very positive, as if nothing happened to them.”

Montenegro said it will likely take years for the Philippines to recover from the typhoon, and the region is still in need of outside help.

In addition to medical workers, he said he hopes more psychologists can go to the Philippines to help the typhoon victims overcome emotional wounds. He came to the Philippines because he wanted to do more than just donate money to a cause. Montenegro, a Pilipino himself, says he hopes to return to his home country soon to help again.

“This is the best thing I’ve ever done in my life,” he said. “I guess our help might have been small, (but) I think it made a big impact.”