As anyone who has ever struggled with mental illness will tell you, fighting a battle against yourself can be both consuming and miserable.

But a new proposed law, in an attempt to help, could make that battle even more challenging.

A House of Representatives committee is currently considering the Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act, which sets out to improve nationwide mental health laws and programs but raises a number of concerns in terms of medical privacy and the definitions of mental illness.

The bill would amend the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act to allow mental health professionals to notify parents or caregivers if a person over the age of 18 is struggling with serious mental illness. Both laws would have prevented this action previously, since FERPA requires colleges to get a student’s permission before releasing any records to caregivers and HIPAA mandates medical record privacy.

So under the proposal, if you’re a UCLA student, and you visit Counseling and Psychological Services because you’re struggling with depression, anxiety disorders or any number of mental illnesses, your parents could be contacted at your counselor’s discretion if he or she thinks you need additional support – regardless of whether you want them contacted or not.

The act is an understandable response to nationwide mental health concerns in the wake of recent mass shootings. But even for the sake of public safety, sacrificing the sanctity of every therapist’s office in the country is not worth it.

The problem with the proposed law is not in its intentions, which are clearly admirable. The problem is that in practice, disclosing the medical information of a legal adult without his or her consent is wrong, regardless of circumstances.

Further, the bill does not specify what the limitations are on what illnesses caregivers can be notified for – one of the only requirements is that the patient has been diagnosed with an illness found within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. So long as the therapist determines this diagnosis to be a substantial interference in the patient’s life, he or she would have free reign to involve the patient’s parents.

Not only does this leave a great deal of leeway for abuse, but it means that the law may place depression, anxiety disorders and even eating disorders on the same level as conditions like schizophrenia.

In addition to failing to distinguish among mental health issues, the bill offers no written specifics outlining how extreme a situation has to be before caregivers can be contacted. Does someone have to be suicidal in order to qualify?

Moreover, the legislation fails to address what will happen after parents or caregivers have been notified. If someone’s parent is a contributing factor to his or her mental illness as a result of physical or emotional abuse, involving them can be more detrimental than helpful. Many adults have no relationship with their parents at all, or do not wish to be in contact with them regardless of the circumstances, something the proposed law fails to take into account.

“There’s no such thing as an intervention that doesn’t have unintended consequences,” said Howard Adelman, a professor of psychology at UCLA.

Adelman said the biggest concern is how reporting can be done practically. Mental health professionals would have to receive additional and specialized training, and those who do a greater-than-average amount of reporting may need to be evaluated or offered additional training.

Until these questions are answered, Congress would do well to respect both professional psychological ethics and the basic principle of patient-physician confidentiality.

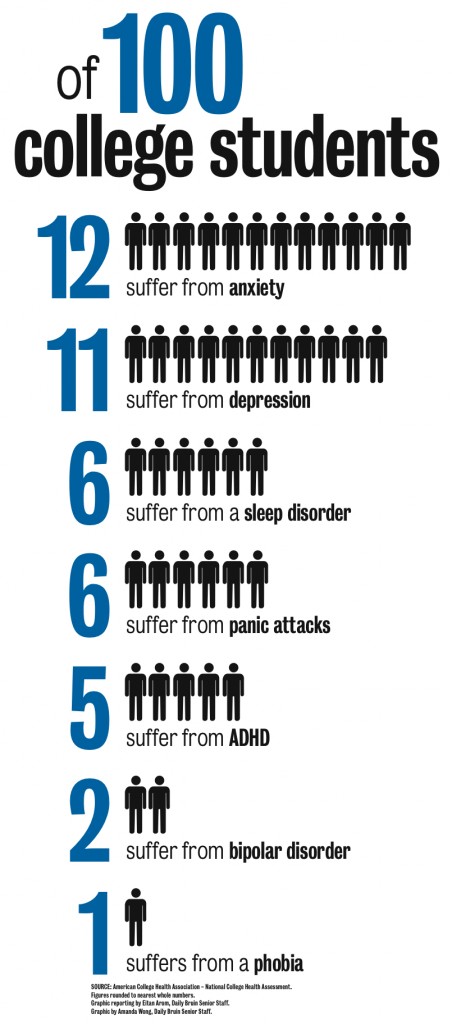

With 25 percent of college students struggling with mental health issues, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the law could substantially impact the UCLA student population. It could also be problematic for students seeking to gain some space and independence from their parents.

What happens in therapy should stay in therapy, and the law must be crafted to reflect that.