Forrest Bess was an artist caught between two worlds, and this internal struggle can be viewed within his artwork shown at the Hammer Museum.

For the first time in over 20 years, the abstract expressionist painter Forrest Bess’ work is being displayed, with a total of 50 pieces of his artwork from 1946 to 1970. Organized by the Menil Collection, this endeavor, titled “Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible,” will include an introduction by Robert Gober, the designer of the exhibition, as well as an essay by Clare Elliott, an assistant curator in charge of the Menil Collection. The exhibition will run at the Hammer Museum in Westwood until Jan. 5 of next year.

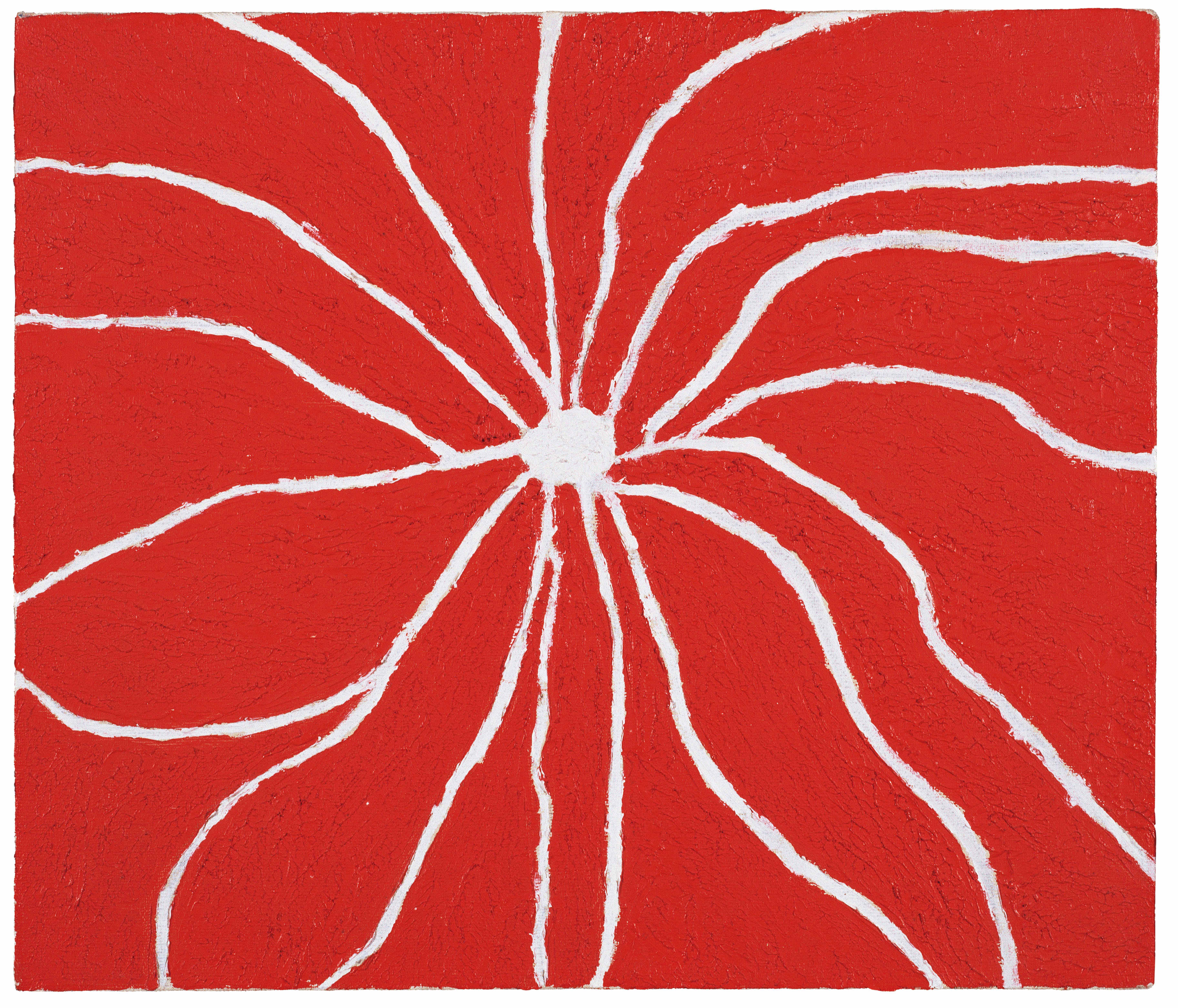

Bess (1911-1977) was a painter from Texas who used both expressionist and symbolist themes and is known for his naturalistic, ethereal works.

“The popularity of his work has experienced a resurgence lately, which can be explained by the nature of his work, as it focuses on natural, primal settings, which is in stark contrast to today’s technologically centered world,” said Chuck Smith, who directed a film about Bess.

This internal struggle formed Bess’ artwork and his style as a whole.

“Bess was a fisherman in the city, which in itself is a contradiction, and he was a man between two worlds, but Bess needed that dichotomy to propel and motivate his art, and it was created in order to challenge the structure of what we value,” said Gober after seeing Smith’s film, “Forrest Bess: Key to the Riddle.”

Gober contacted Smith to organize a showing of Bess’ work together. Elliott was organizing her own show at the same time, and the three decided that a show in conjunction would be the best avenue to take.

“The relationship between Gober and Bess is due to their similar viewpoints regarding the message of their artwork,” Smith said.

Their similarities in telling stories through art explains Gober’s respect for Bess’ work.

“Gober also tells stories with his own art, so I think that’s why he was so drawn to Bess’ work. I think he wanted to fulfill Bess’ intentions. Gober’s art can be very explicit, and so can Bess’, so I think Gober wants to afford Bess the same opportunity,” Smith said.

Smith’s interests in Bess’ work stem from his own love of art, and first spawned after seeing a collection of Bess’ work in 1988 – the first time such a large collection of Bess’ work was accumulated in one place because of how difficult it is to collect them.

“I’ve been a fan of Bess since I got into art when I was a freshman, and getting to see this much of his art is definitely a treat,” said Anant Randhawa, a fourth-year neuroscience student who frequents the Hammer Museum.

The opportunity to see Bess’ inspiring work comes with a tinge of sadness, however, as the Hammer exhibit isn’t displaying his work in its entirety.

Because of a hurricane that hit the gulf coast of Texas in 1961, where Bess had made his residence, a large portion of his work was lost. This calamity is why the exhibit only has expressionist pieces from his earliest years dating to 1970, which is also around the time that Bess stopped painting.

“The exhibit only covers expressionist pieces from his earliest years dating to 1970, when the hurricane hit,” said Leslie Cozzi, a curatorial associate who assisted the Hammer show.

Exhibition-goers can look forward to seeing various different kinds of Bess’ art, as works such as “The Spider” and “Hermaphrodite” will be on display.

“Bess’ work includes semi-expressionistic, semi-symbolist pieces on these very small, abstract canvases – where the sections of the body and the landscape are allied so they are not quite one genre or the other, but draw on both motifs to create very interesting abstract mixes,” Cozzi said.

“This is the opportunity of a lifetime,” Smith said. “In this technological world, we need this exhibit more than ever; it’s the balance of the natural and primal.”