Pink brains about the size of fists laid on trays in a medical school teaching lab, moments before they were sliced open by eager hands.

Students clad in white lab coats and goggles poked and prodded the brains, armed with only some basic medical tools.

The aspiring researchers are students aged from 12 to 18 who participated in summer neuroscience workshops put on by the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center in an effort to educate kids about the basics of the brain.

In the 20-student workshops, participants dissected sheep brains, learned about anatomy and participated in interactive lectures about brain injuries.

The classes cost $250-350, primarily used to buy supplies for the class, as well as fund UCLA neuroscience research.

Mayumi Prins, a professor of neurosurgery and director of the BIRC education program, said the classes allow kids to apply what they learned to their own lives.

“When the brain is injured, perhaps through sports, you might not be able to see or feel it,” Prins said. “It’s important to teach them how to listen to what the brain might be trying to communicate.”

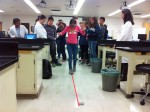

In one activity, students attempted to walk along a straight red line wearing goggles designed to mimic the effects of a concussion on coordination and eyesight.

After the students stumbled and fell while wearing the goggles, Prins explained the importance of recognizing the symptoms of a brain injury so students could seek help immediately.

Wearing full lab gear, the kids cut pieces of the sheep brain and identified important structures.

Oliver Powell, 13, said he wanted to take the class because science is his favorite subject and learning about neuroscience hands on seemed like a fun experience.

“I didn’t realize how soft the brain is until I was actually able to hold one,” said Powell, who wants to start a company to fund biomedical research when he is older.

Faculty from the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center have been traveling to local middle schools and high schools to educate students about brain injury prevention since 2003.

Last summer, the center began to offer one- and two-day summer workshops for students who wanted a more in-depth experience with neuroscience, Prins said.

Graduate students from Prins’ lab and UCLA faculty donated their time to teach the class.

Tiffany Greco, a UCLA postdoctoral fellow who volunteered to help teach the class, said she thinks adults have a responsibility to educate kids about the consequences of repeatedly injuring their head and brain.

“It’s exciting to talk to the kids about the possibilities that are out there for them,” said Daya Alexander, a UCLA graduate student who helps teach the workshops. “It’s critical that they are exposed to as much knowledge as possible, even if they don’t end up pursuing neuroscience in the future.”

Prins said the workshops are still in the preliminary stages, and the center will apply for education grants to help expand the number of students they reach.

She added that she hopes they will be able to provide more scholarships.

Thank you for sharing! I have learned so much from this post. Buyincoins

its nice discussion concerning this article here at thisweblog, I have read allthat, so at this time me also commenting at thisplace.

Here is my web blog http://www.spy-cameras-stores.com