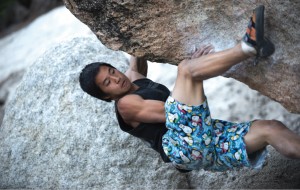

In the forest of Mount San Jacinto State Park, six friends from UCLA spent a recent Sunday climbing seemingly sheer rock face.

While the ordeal might appear too thrilling for many, it’s just another day for this group of UCLA climbing enthusiasts, who engage in this type of climbing – called “bouldering” – nearly every weekend.

“Indoor climbing is good for staying strong, but I don’t think it’s as rewarding as climbing outdoors,” said third-year environmental science student Daniel Fong.

On this particular trip, one climber had a better perspective than most on the relative advantages of climbing indoors and outdoors.

Will Conley, now a mathematics professor, began climbing roughly 10 years ago as an undergraduate student at UCLA.

“It was something I always wanted to do,” Conley said. “I like the movements and techniques of climbing.”

Conley’s desire for new climbs and new mental challenges soon extended to outdoor climbs, where there is a greater variety of climbing opportunities requiring an array of strategies and techniques.

“You have to plan almost every move of your climb,” said Ian Zemke, a graduate student in mathematics.

A “problem,” he explained, is essentially a route up a boulder or cliff, which climbers must solve step by step, deciding where their next move will be.

“Climbing is a weird sport because it is about finding the hardest way up,” Fong said.

Climbers grade the difficulty of a climb based on a V scale ranging from V0 to V16, with V0 being the easiest and V16 being the most difficult. During their trip to San Jacinto State Park, the climbers scaled everything from V1 to V10 climbs. These climbs provided an array of obstacles, from simple climbs up flat rock face to more complicated climbs with overhangs and sparse footholds.

But there are more factors at play in a climb’s difficulty than the physical features.

The sheer height of outdoor climbs, combined with the lack of ropes in bouldering, can pose a psychological challenge to many climbers.

“The challenge for me is staying collected and calm on high climbs,” said third-year political science student Guillaume Hansel.

The natural elements also add another dimension of difficulty to climbing outdoors. Climbers said weather conditions such as rain and snow can affect rock and make it difficult to grip. Even the composition of the rock can affect the climber’s strategy.

“We really pay attention to the kind of rock we are climbing,” Fong said.

The rocks can range from sandstone, which is smoother with “slopes” or “slope-y holes,” to granite, which tends to have more crimps or small crevices for gaining a hold.

In order to prepare for the unpredictable elements of nature, climbers constantly sharpen their own skills with hours of practice both indoors and outdoors. Conley said many climbers practice two or three days a week for a few hours at a time.

Between time spent at the Wooden Center and nature trips almost every weekend, the UCLA climbers especially take comfort in having the opportunity to spend time bonding with one another.

“I really like the social aspect of it,” Hansel said. “You just get to hang out with friends and climb.”