Thousands of University of California patient care technical workers are planning to walk off the job in protest of poor conditions for both employees and patients within UC medical centers.

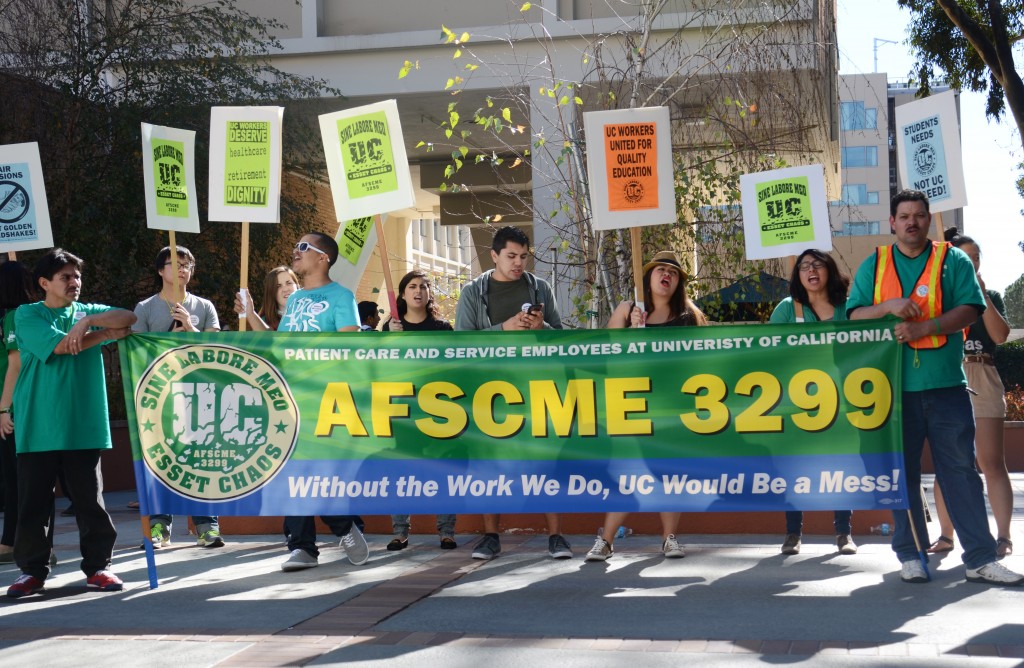

Negotiations between the workers’ union – the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Local 3299 – and UC representatives have dragged on for almost a year, and have culminated in a strike planned for May 21 and 22.

A number of UC officials have claimed that the union’s major demand – revised staffing standards to ensure quality patient care – is simply a public relations move that masks what workers are really dissatisfied with: pension reform. In other words, the union seems to be using the issue of hospital conditions as a smoke screen, pretending the strike is about more than just financial compensation.

If the union can work with the UC to resolve the dispute over pension reform, room will be created for more substantial discussion about the caliber of health care that the university’s medical centers can offer.

Pension reform at the UC started several years back.

For years, UC employees had contributed part of their salaries to the university’s pension fund. When a large surplus accumulated in the 1990s, however, the UC suspended contributions and funded pensions through investment returns.

Eventually, it became clear that this funding model was unsustainable, and the UC reinstated employee and university contributions to the pension fund. For employees, this change means they have to put part of their paycheck into the fund – it is essentially a pay cut.

Additionally, for patient care workers, the UC has proposed increasing the retirement age to 65 from 60, said Mark Speare, senior associate director of patient affairs, human resources and marketing for the UCLA Health System. From the UC’s point of view, pension reform is needed to cover a $24 billion liability and ensure the stability of the pension system in the long run.

The union’s main sticking point is the high amount of executive pensions.

The average patient care worker receives $25,000 per year after retirement, said Todd Stenhouse, a spokesman for the union. In contrast, hospital executives at UCLA are paid an average of $60,000 per year after they retire, and the union wants to cap that number.

Stenhouse said a cap could create money to put toward new equipment and the hiring of more workers.

The union has linked conditions in medical centers to the issue of pension reform. It only seems reasonable that the union should go straight to the heart of the matter and discuss pensions with the university.

Then, the union could have a productive dialogue with the UC that is truly centered on patient care and working conditions. After all, the union has raised multiple concerns – and though these concerns may turn out not to be valid, they are worth looking into.

The union released a report, “A Question of Priorities: Profits, Short Staffing and the Shortchanging of Patient Care at UC Medical Centers,” which found deficiencies in patient care at hospitals. University officials have disputed some of the findings of this report.

Another of the union’s main complaints is how understaffed UC hospitals are. At least within the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, staffing numbers seem to have actually increased slightly since 2008, with an 8 percent increase in employee numbers.

But a third party could help determine whether this number is still considered understaffed for the hospital.

According to the Daily Cal, California State Sen. Ed Hernandez, D-West Covina, chair of the Senate Health Committee, has said state lawmakers will look into some of the union’s allegations.

In anticipation of the upcoming strike of patient-care technical workers, the UC is currently negotiating a restraining order. The idea behind the restraining order is to prevent critical employees from participating in the strike, Speare said.

“We are currently working with the union’s attorneys to get a list of people whose jobs are considered critical to show up to work to ensure patient safety,” Speare said.

The union gave a 10-day notice that it would be striking so that the UC hospitals could compensate for workers’ absences and ensure patient well-being, Stenhouse said.

These measures show the wide-reaching impacts that a strike of medical system workers can have. Clearly, it is important for the UC and the union to reach an agreement.

In the past, when the union has gone on strike, the UC has shown its willingness to negotiate and compromise. Now, the union should engage with the university on the issue of pension reform. Perhaps then the issue of medical center conditions could be addressed transparently and effectively.

Email Freedman at

zfreedman@media.ucla.edu. Send general comments to

opinion@media.ucla.edu or tweet us

@DBOpinion.