Although Leon Levitch and his family were sent to a concentration camp north of Milan during World War II, the Italians didn’t treat them like enemies.

“They interned us in a beautiful resort near the Alps,” said Levitch, a Jewish composer and Holocaust survivor. “You see, the Italians will make you prisoners, but they won’t deny you of music.”

Levitch said it was the existence of a piano that allowed for music to maintain their livelihood. Each day, the Jews in the camp would be allowed to play for an hour or two starting in the early morning.

“The mornings were very cold and no one wanted the piano then because your fingers wouldn’t work, so I was given the coldest hours,” Levitch said. “My mother – and I don’t know how – she managed to get a hold of a hibachi so I could warm my hands and play.”

The Levitches only remained there for a year and a half before being sent to a camp in southern Italy where they were fortunately soon liberated. Levitch and his family were among the 1,000 Jewish refugees allowed into the United States and housed at the Oswego military base in New York until the end of the second world war.

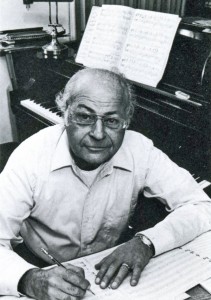

Levitch then went on to pursue his musical career, attending the Los Angeles City College for a brief period before receiving his master of arts degree in composition from UCLA.

Tonight, three students from the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music will perform Levitch’s Trio, Op. 2, a showcase of the flute, clarinet and piano, as part of the department’s seventh annual “It’s a Woodwind World” concert.

Levitch said he began composing music at around 6 or 7 years old, as he grew up with parents who played piano themselves. Although he appreciated the free form and creativity of writing original compositions, his father didn’t approve.

“My father thought my compositions were … nothing serious,” Levitch said. “He thought my music should focus on great composers like Beethoven or Mozart.”

In spite of this, Levitch said music helped him through his moments of loss and hardship, like when he stayed at the concentration camp in the Alps.

Not only was Levitch able to play the piano frequently while in the Italian camp, he was able to learn from Vera Levenson, a fellow refugee and pianist in the camp who gave him private lessons during his stay. Levitch said he played what he heard and what he was taught, mainly Levenson’s favorite pieces by Bach.

“She gave me lessons whenever (the piano) was available,” Levitch said. “That was a wonderful thing to find her there.”

But Levitch admitted that with the horror of escaping the Nazis, there was little else that entered anyone’s thoughts during those times, music included.

After the war was a different story. Levitch said he began composing again and studied under musicians who became his greatest inspirations, including Florentine composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco and Viennese composer Eric Zeisl.

A few years later, in 1952, Levitch wrote Trio, Op. 2 as a memoir to the passing of his friend, Victor Pilch.

In spite of the sorrow that inevitably enters the work at certain points, Gary Gray, clarinet professor and one of the faculty involved in organizing the concert, said the Trio plays out with an expressive melodic development that is similar to how a short story unfolds.

“The Trio takes you through different (elements), almost like a travelogue of someone’s life in miniature,” Gray said. “There is some tragedy but there is also a picture of life that is constantly attracting you.”

Dawn Hamilton, a first-year graduate student who will play the clarinet part, said one of the greatest challenges in learning the piece lies in the nature of the sheet music: handwritten. With lines of music literally cut and pasted together at certain parts, the composition visually takes more time to read.

But aside from the physical composition, Cleopatra Talos, a fourth-year graduate student who will play the Trio’s flute part, said the complexity of Levitch’s piece makes it more lyrical than traditional trios, which are often thought of as being a little dry.

Talos said she appreciated how Levitch didn’t complicate or make the meaning of the piece overly abstract. Instead, he strung his notes together in an expressive way.

“The way the instruments interact makes the piece move forward very well and it doesn’t sound like a trio,” Talos said. “The lines are not singled out or lonely in their own way. They harmonize so well that it sounds like an ensemble.”

Gray said Levitch isn’t a composer who throws out the constructs of 20th century composition. Rather, he takes on his own version of traditional elements like the theme of variations in the first movement. Yet at the same time that it upholds a certain element of continuity, the composition also maintains surprise for the audience, whether they be music-educated or not.

“You don’t need to spend 20 minutes reading the program to convince yourself that what you heard was a good piece,” Talos said. “Music is what it tells people and what it makes them feel. (This Trio) will give audiences an energy and I (hope we’ll) be able to do it justice.”