In Chile, it is not rare to see tens of thousands of protesters marching through Santiago’s main thoroughfares during a demonstration for education equality. Protesters represent a wide demographic range, from students to teachers to parents, grandparents and siblings.

A large sector of the public is frustrated with what they say is a system where wealthier students have numerous advantages in gaining admission to the country’s top colleges. Though government officials have responded with some revamped policies, many protesters continue to demonstrate. They demand free education and constitutional change. These are the faces of protest.

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”300″]

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”300″]

Julia Villarruel

American activist

At the suggestion of a friend she met in a hostel, Julia Villarruel went to her first student-led march four days after arriving in Santiago, Chile, in June 2011 for a University of California Education Abroad Program.

It was there that Villarruel, now a fourth-year political science student at UC Berkeley, first tasted a typical protest: peaceful chanting, dancing and flag-waving that unraveled as police broke up the crowd with tear gas and water cannons. She said she had watched friends of hers join protesters to occupy Sproul Hall at Berkeley in 2009, but it was a smaller-scale action than this.

“I had never seen anything like it,” Villarruel said. She was hooked.

Villarruel originally only planned to stay in Santiago for a semester, but she fell in love with the Chilean student movement. She extended her stay twice, was arrested once and took part in more than a dozen large-scale marches and demonstrations.

To “catch up” to her new Chilean friends’ level of knowledge, Villarruel pored over newspapers and blogs, learning about the country’s dictatorial history. She said she picked up a new perspective from Chilean protesters during her months away from home: When an entire student community gets involved, it can drive real results.

“I lived and breathed this movement,” Villarruel said. “It’s all I did, all I focused on.”

Villarruel said that before she lived in Chile her experiences taught her that education should be free.

Her mother and father grew up in Mexico and Argentina, respectively, where public primary schools are free. Her time at Berkeley has been funded almost entirely by a scholarship.

Months ago, Villarruel got an outline of Chile tattooed on her spine. The procedure was painful but symbolic.

“Even after one year, this country made a mark on me,” Villarruel said.

Now back in the U.S. after a year and a half in Santiago, Villarruel said she plans to tour UC campuses to share her vision for a Californian student movement – one with localized cells of activists, like in Santiago. These groups would come together under a statewide coalition but work mainly on their individual campuses to rally the most students possible.

“Putting ideas to practice is the best possible way for me to continue the lessons learned from Chile,” Villarruel said. “I feel a responsibility to start conversations about our UC system.”

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”300″]

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”300″]

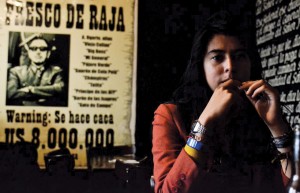

Daniela Coto

Marching through gas

Daniela Coto held a sliced lemon, a remedy for the burning sensation in the throat that comes with tear gas.

Police use gas and water cannons to disperse lingering protesters after a march’s designated end time. Coto, a psychology student at the University of Chile, stood nearby when police threw a gas canister into the crowd at a Aug. 28 march for education.

Soto said marches are a way to show Chileans that student protesters are a bigger population than the press makes them out to be.

“I know at the end (of a march) there will be fights with police, but that doesn’t scare me,” she said. “The message we’re sending the government is that we’re not the minority; we’re the majority.”

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”184″]

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”184″]

Gustavo Beaufont

Protesting father

Gustavo Beaufont rode his mountain bike during a family bike ride for education during August.

Beaufont’s son goes to private school. He receives specialized training for Chile’s college entrance exam, so he’ll almost certainly get accepted to an elite university, Beaufont said. But Beaufont said he braved the chilly nighttime protest because he knows the majority of Chileans don’t have the money to give their children similar preparation.

“At the tomas, kids have been hit and kicked,” Beaufont said. “I’m just standing here in a little bit of rain. That’s small compared to what they’ve done.”

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”300″]

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”300″]

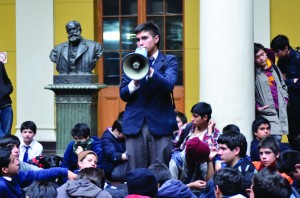

Jorge Villas

Public school student

Jorge Villas called for a vote from about 30 of his classmates to decide whether to stage a toma, or student takeover, at their public school.

Students from Instituto Nacional, one of Chile’s most prestigious public schools, had met at the University of Chile administration building where their college counterparts were camping out.

“We have a basic right as students to a free quality education,” Villas told his classmates. “Even though it’s a long and hard process, we have to do something because the adults in our country aren’t doing anything.”

A toma at Instituto Nacional began a few days later.

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”300″]

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”300″]

Ariel Devila

Supporting the test

Ariel Devila showed off a poster of Manuel Gutiérrez, a student who died from protest-related violence.

Devila studies at a private school, yet he marched in remembrance of the public school student he never knew. Devila wants to pursue art in college. He said he thinks he’ll get into the University of Chile.

“There needs to be more equality in education,” Devila said. “The support we get from university students helps. If we march in a big mass of people, people will listen to our ideas.”

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”198″]

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”198″]

Anael Gutiérrez

Struggling to keep up

Anael Gutiérrez will have to pay about 15 million pesos – or almost $32,000 – in loans when he graduates from the University of Chile a few years from now.

From a poor high school in the beach town of La Serena, Chile, Gutiérrez was the only one in his class to be accepted into what is arguably Chile’s most respected university.

After he failed four college courses, though, he no longer qualified for his full scholarship and scrambled to find loans. His classmates who went to expensive high schools don’t struggle with school like he does, Gutiérrez said.

“I lost my scholarship because I didn’t have the same education foundation as all of my peers,” he said. “They were more prepared than I was.”

Gutiérrez works part-time at a grocery store to cover the costs of books and food while he takes classes in public administration. He said he’s optimistic he’ll be able to repay his loans after college, because a degree from the University of Chile has high earning power.

Many students from poor backgrounds, however, can’t anticipate such high earnings and are forced to drop out of college, he said.

“When you enter the university with a very basic education, it’s difficult to get good grades and maintain a scholarship,” Gutiérrez said. “That’s why a lot of poor students leave. The current system creates a cycle.”

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”198″]

[media-credit id=693 align=”aligncenter” width=”198″]

Emmanuel Aguilar-Posada

UCLA student

A fourth-year anthropology student at UCLA, Emmanuel Aguilar-Posada studied abroad in Chile for six months in 2012.

He would have attended classes with Chileans at the University of Chile – if the campus was not on strike. When classes were cancelled for two weeks in August, Aguilar-Posada met privately with his professors and continued turning in assignments so he would still receive credit for coursework and avoid falling behind at UCLA.

“It’s my responsibility to deal with my grades, and I have no problem with that,” he said. “I value the strikes as part of my experience here. They’re part of the culture.”

When class is in session, Aguilar-Posada said student movement leaders often stop in during the last few minutes of a lecture to ask for feedback about the week’s protest efforts and advertise upcoming events.

Aguilar-Posada said he finds Chilean students more politically conscious and aware of global happenings than his friends at UCLA. He once debated American health care options with a friend who had never left Chile. The friend won.

“Chileans are more well-spoken than Americans,” Aguilar-Posada said. “Ideas just shoot out of their mouths. It’s intimidating.”