When Jean Rouch brought his 16mm Bell & Howell camera to West Africa in 1946, he was not a filmmaker, but a civil engineer. Little did he know, the documentaries he would make would define his career, solidifying him in the annals of film.

Rouch was a pioneering filmmaker – his work is diffused through a multitude of genres including visual anthropology, French New Wave, cinéma-vérité and ethnofiction, which is a mix between documentary and fiction. However, Rouch’s films have predominantly been shown in France and have remained largely unseen by American audiences. The UCLA Film and Television Archive is finally bringing to light this influential filmmaker’s works in “Farther than Far: The Cinema of Jean Rouch,” which is playing at the Billy Wilder Theater in the Hammer Museum until Feb. 23.

“Rouch is amongst the most significant contributors in the realm of documentary filmmaking at least within the last 50 years and maybe in the entire history of documentary film,” said Michael Renov, a professor of critical studies at USC and a scholar of documentary film.

Jump cut sequencing, tight frames and self-consciousness of the film are all staples of the French New Wave and standards of contemporary film technique. These techniques didn’t exist before Rouch, said Robert Lemelson, professor of anthropology at UCLA and a documentary filmmaker.

Jean Rouch began his filmmaking career with works like “In the Land of the Black Sorcerer” and “Initiation Into Possession Dance,” a film that documented sacred possession rituals of the Songhai, Zarma and Sorko peoples in French-occupied Africa.

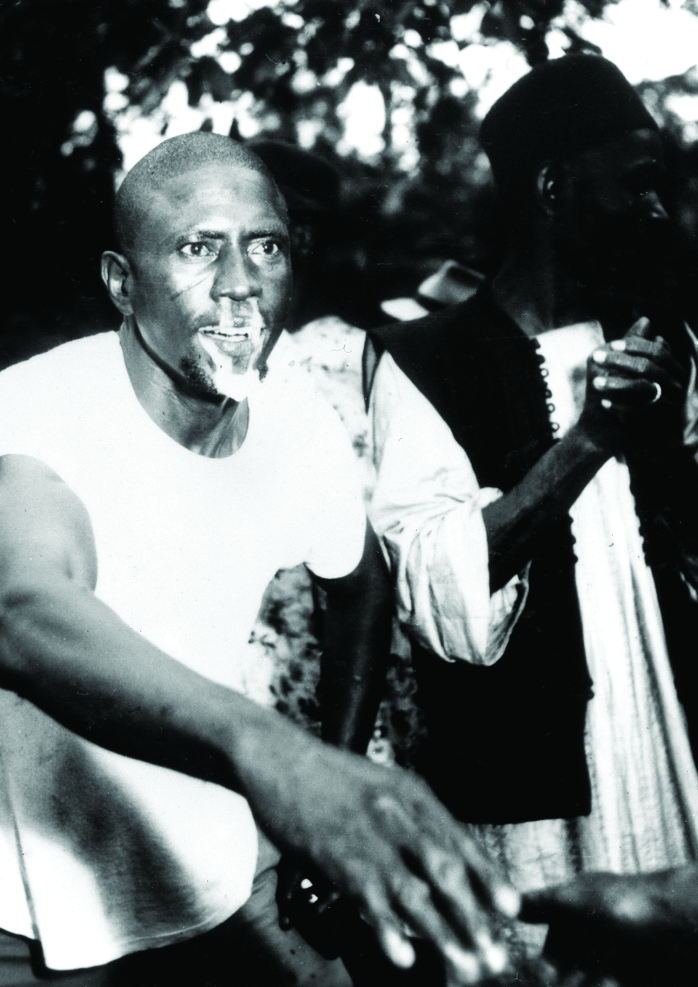

Many of his early works revolved around African tribal practices, including the work “The Mad Masters.” The film documents the Hauka movement, a form of resistance in West Africa to British colonization in which members became possessed by spirits associated with Western colonial power in order to mimic and parody their pretenses.

“Rouch was directly influenced by the philosophical assumptions of African people. He believed that their power was able to change people’s lives,” said Shannon Kelley, head of programs at the UCLA Film and Television Archive. “He realized that this is something so profound that this deserves people’s attention and respect.”

Although many critics have praised Rouch’s critique of British colonialism, he has also been no stranger to controversy. Because of his status as a French man in colonial Africa, many critics claimed his films depicted Africans as savage, uncivilized people.

“(Rouch) knew that he was incriminated by virtue of the discipline he was practicing,” Renov said. “But he didn’t let that stop him because he believed in the power of people to create new possibilities.”

Rouch used his filmmaking to confront the backlash of African communities towards colonial powers.

“Colonial presence was everywhere in anthropology up until the 1940s and ’50s. But, I think it was possible even in that time for people to escape the shackles of a colonial consciousness,” said Lemelson. “Rouch went back to Africa over and over again, forming long-term relationships and deep connections through his work. That was one way to escape those shackles.”

While living in France, Rouch was heavily influenced by surrealist painters and jazz musicians, incorporating many of their creative tendencies into his filmmaking.

“He was a strong believer in the power of chance and things that come up accidentally. … Improvisation was a strong driver of his work,” said Kelley.

These techniques created a new aesthetic in film.

“There was a new sense of chance and openness in the frame … the sense that the camera is not an invisible thing and should not be ignored,” said Kelley.

Rouch’s technique of improvisation and the reflexivity of his films are prevalent in his later works of ethnofiction. “Chronicle of a Summer,” his most famous work, co-directed with sociologist Edgar Morin, creates a portrait of French contemporary society by interviewing Paris residents during the summer of 1960.

Although Rouch’s films have been difficult to see in the United States, thanks to new interest from academic and film institutions such as the Anthology Film Archives in New York and UCLA’s own Film and Television Archive, Rouch’s progressive films are finally finding their way to the American public.

“You always feel in a sense with (Rouch’s) work that he’s leaning forward,” said Kelley. “This work is still so far ahead of its time.”

Contact Garrett Anglin at ganglin@media.ucla.edu.