From eerie, bloody portraits of shady figures to portrayals of Mickey Mouse’s death, the Llyn Foulkes exhibit at the Hammer Museum is highly emotive to say the least.

Llyn Foulkes is an artist active since the 1960s whose art reflects his commentary on pop culture and mainstream society, including the Disney character Mickey Mouse. The Hammer Museum is currently showing a retrospective collection on Foulkes that will run until May 19. The exhibit shows 150 pieces from Foulkes’ life, ranging from artwork from his adolescence to works made recently.

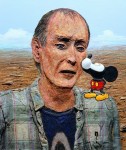

Although he is a contemporary of the pop art movement, Foulkes’ style is far from the colorful Warhols and Lichtensteins that are associated with the 1960s and ’70s. His career experienced several stages in terms of aesthetic direction, but generally held dark messages and deep social commentary on subjects such as mass consumerism. In the 1980s, Foulkes began incorporating Mickey Mouse in his artwork as a way of voicing his opinion on the negative ways cartoons affect the American youth. Mickey Mouse is a recurring character even in his later works including “Corporate Kiss” from 2001, which is a self-portrait of the artist receiving a kiss on the cheek by the famous Disney icon.

“(Foulkes’) father-in-law worked at Disney and showed him the Mickey Mouse Club Handbook, which had messages about implanting thoughts in children’s minds, which seemed like brainwashing,” said curator Ali Subotnick. “He started targeting Disney as a means of showing things going wrong in America.”

In addition to portraying Mickey Mouse in an antagonizing light, Foulkes is also known for his “bloody head” portraits. In the 1970s, Foulkes began developing one of his trademark styles known as the “bloody head.” These images are portraits of various male subjects, typically dressed in black or blue suits, with faces hidden by red paint that resemble drips of blood or severe head wounds. Subotnick said these highly macabre images are considered Foulkes’ way of escaping his consumer art stage, when he mainly focused on painting Los Angeles landscape images for postcards.

“He felt like the landscapes were becoming really formulaic, so he started … his bloody head portraits,” Subotnick said. “Blocking out the eyes in the portraits was important because (eyes) are the keys to the soul. … When you block that out you don’t have that immediate access, so you need to find other ways in the picture to find that access.”

Foulkes began experimenting with more dimensional work as opposed to the flat paint-on-canvas style used in his bloody head portraits. Foulkes’ art dealer, Douglas Walla, said while these images were very dimensional, they still had cartoon characteristics about them that were relevant to his style.

“What he’s trying to do is create a sense of real space. He’s fashioning a very unusual, almost in some cases a pop image, while at the same time being very dimensional,” Walla said. “He’s trying to, within a compressed foreshortened space, create the appearance of an entire room while still having cartoon imagery.”

Though Foulkes is an artist who has created a large collection of work while also changing his style many times, he is often considered under-recognized in comparison to other artists who emerged in the ’60s and ’70s. Professor Russell Ferguson, chair of UCLA’s Department of Art, said this lack of fame is the result of Foulkes’ own decisions to stay away from the spotlight.

“While a lot of people think he should be more recognized, we have to realize he’s made decisions himself that have taken him away from that kind of (success),” Ferguson said. “In that sense, I feel that he thinks if he had too much material success it would threaten his autonomy as an artist.”

Walla also holds the notion that Foulkes avoids excessive media attention. He said that Foulkes’ work is supposed to oppose any sort of branding, which is especially prominent today.

“(Foulkes) is not a commodity. What you have with social media and the general nature of the way social media works is that it’s all around branding,” Walla said. “(Foulkes) is basically the Antichrist of branding. His work has been against that type of brainwashing. Not only does he choose to operate outside of that kind of branding, he’s critical of it.”

Email shin at jshin@media.ucla.edu.