It seems like an aberration. It charts as an outlier.

To watch the Bruins play an up-tempo style of basketball this season is unusual, from an entertainment and numerical standpoint.

He has changed plenty already, but UCLA coach Ben Howland isn’t going to stray from this strategy anytime soon.

“We want to continue to play like this,” Howland said. “This is not a one-time deal.”

Howland has always liked to keep a firm grip on his offense, usually making his point guards jog up the court and wait for his play-call from the sideline.

Between signalling for strategies from the playbook, Howland mixed in a bellowing “Push!” whenever he saw an opportunity to run a fast break.

This season, that instruction goes without yelling.

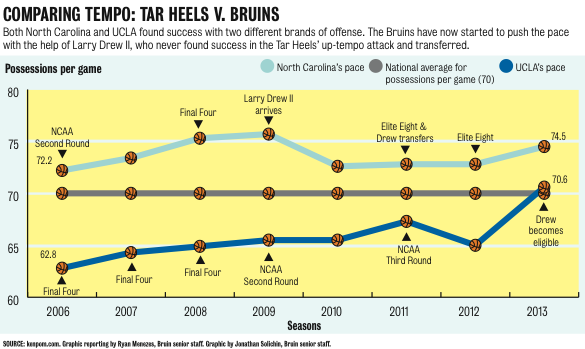

The Bruins are always running, always looking to beat their defender down the court. It has worked so far. During UCLA’s 16-5 start, it has played at a pace of 70.6 possessions per game, according to data from kenpom.com, the first above-average mark since before the Bruins made their first Final Four.

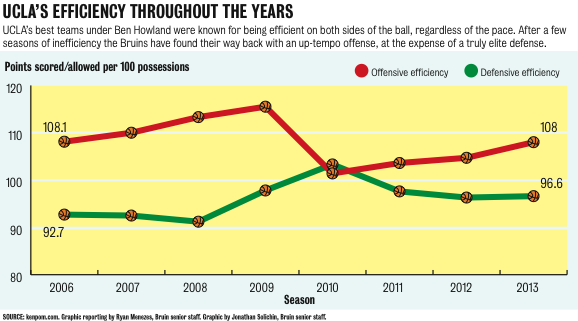

That’s one of the fastest tempos in the country and it has resulted in the Bruins scoring 108 points per 100 possessions, making them one of college basketball’s most efficient offenses.

While Howland’s best UCLA teams were stifling defensively – a standard Howland won’t stop holding the Bruins to – this season’s team has sacrificed defense for offense. The raw scoring numbers show UCLA tallying one of the highest point totals in the country. Conversely, the amount of points UCLA’s opponents have scored this season is one of the worst marks nationwide.

So UCLA has gone all in with trying to out-offense the opposition.

“We have two points guards in the game a lot of the time, the Wears are great at running the floor and our wings are really good scorers and shooters,” Howland said, explaining the success of his revamped offense.

The effects have also been felt on the recruiting trail.

“That’s been the knock on us recruiting-wise: really slow basketball, Coach Howland’s going to dictate tempo,” UCLA assistant coach Korey McCray said.

Now, the foundation of UCLA’s up-tempo attack has been laid by Howland for the Bruins on the horizon.

Speedy point guard Larry Drew II graduates after this season and some freshmen may go with him, but UCLA’s future is solidified. The Bruins already have commitments from Zach LaVine, Allerik Freeman and Noah Allen for the class of 2013. Those three stand 6-feet-3-inches, 6-feet-4-inches and 6-feet-6-inches, respectively.

The Bruins aren’t looking for bruising bigs, only the fleetest of foot.

UCLA’s future, like its present, is fast.

Carry The One

The basic tenet of the storied North Carolina basketball program is this: get the ball and run.

Larry Drew II arrived at the school as a highly touted freshman, one known for how fast he could dribble the ball. The 6-foot-2-inch point guard was to use his speed as much as possible, following the legacy of other fast floor generals who thrived in the up-tempo attack.

He played sparingly his freshman year, watching as the Tar Heels won their second national championship in five years. That season, North Carolina was one of the fastest teams in the country.

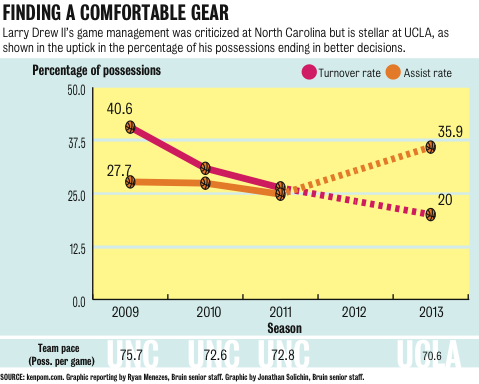

Drew’s first chance to lead the team was his sophomore year, but his play was a microcosm of North Carolina’s disastrous season. Decisions got sped up and he usually made the wrong ones. Drew was quick, but he was also hurrying.

“I’m trying to force the issue even though my natural instinct was ‘Nah, not this time. Slow it down. Get something else.’ Over there, it was ‘We still have to push it,’” Drew said. “You start thinking too much, you start to overthink things.”

Midway through his junior season, after getting benched, Drew bolted from North Carolina without saying a word to his coach. He returned to his hometown of Encino, a stone’s throw away from Westwood, and enrolled at UCLA shortly thereafter.

[media-credit id=4371 align=”alignright” width=”585″]

[media-credit id=4371 align=”alignright” width=”585″]

Drew ran away from one speedy team. He unexpectedly ended up with another.

He and the Bruins have fared just fine.

Drew controls offensive success like he never could at North Carolina. When a Bruin grabs a rebound or takes the ball out of bounds after the other team’s made basket, he looks straight to Drew to get the offense started. From there, Drew is making the right choices.

He left North Carolina after three seasons in which he turned the ball over more frequently than he found teammates for assists. At UCLA, Drew is logging a higher assist rate – defined as the percentage of possessions resulting in an assist when he’s on the court – than turnover rate for the first time, according to kenpom.com’s database of college basketball metrics.

UCLA coach Ben Howland took a chance on a castoff who basically quit on North Carolina in February of 2011, a situation Drew still expresses some regret over because of the way he handled it.

Drew so wanted to be at UCLA that he was fine with Howland not having a scholarship ready for a mid-year transfer. His family even footed the bill for a quarter of tuition. After that, he sat out a season per transfer rules as UCLA slogged to a 19-14 record, a season made even more unwatchable because the Bruins were slow and ineffective on offense.

[media-credit id=4371 align=”aligncenter” width=”479″]

[media-credit id=4371 align=”aligncenter” width=”479″]

Not only has Drew been the fast-break catalyst Howland envisioned, he’s taking care of the ball better than any point guard Howland has had in four seasons.

Howland says he had no reservations. Drew cited personal issues, not the benching, as the main reason for his departure. But instability off the court clearly compromised his ability to lead a team.

“I think a lot of his success has to do with being happy,” said Howland of Drew, who is now back home and has family watching him at every home game.

Last Thursday in Tucson, Ariz., Drew’s leadership in UCLA’s running show was on display. The Bruins jumped out to a 21-5 lead against the No. 6 Arizona Wildcats and never looked back. Drew had nine assists and just two turnovers, keeping his foot on the pedal even as his team’s lead kept getting bigger.

“How we got the lead in the first place was running,” Drew said after the win. “We didn’t want to slow it down at all. I haven’t seen a team so far this season that can stop us from running effectively.”

Drew’s father, his namesake, was also a point guard. He spent the last part of his playing career on the Los Angeles Lakers teams known as “Showtime” worldwide.

Showtime was born of the talents of Magic Johnson, who had a flair for entertaining with the way the Lakers ran on offense. Little Larry watched as his dad played the role of Magic’s backup.

“They were all in sync,” Drew recalled. “When you have a point guard like Magic, whose vision is incredible, and he’s able to push the ball the way he can, it’s Showtime.”

It’s also an alluring style of play to impressionable young players. Five years ago, Drew chose to go to North Carolina in part because of the Tar Heels’ propensity to push the ball.

Howland had recruited Drew, who starred at nearby Taft High School in Woodland Hills, but withdrew his scholarship offer during the process. It’s a decision Howland now says he botched.

Otherwise, who knows when this new brand of Bruin basketball would have started?

Explaining The Numbers: Picking A Pace

Counting the number of possessions – the period defined by control of the ball on offense before giving it back to the defense via turnover, or by missing a shot and not grabbing the rebound – is the best way to measure a team’s pace in basketball.

In the world of men’s college hoops, where the shot-clock starts at 35 seconds, the average 40-minute game has close to 70 possessions. Each season, that average is trending downward with more teams choosing methodical strategies, but North Carolina consistently ranks well above the mean. UCLA is usually well below, until now.

Comparing the raw numbers of fast and slow teams is an apples-to-oranges exercise. Faster teams will accumulate more statistics because they use more possessions.

The Bruins used to be proof of the fact that it wasn’t how many times you possessed the ball but what you were doing with it. Quality over quantity. Calculated, not chaotic.

[media-credit id=4371 align=”aligncenter” width=”578″]

[media-credit id=4371 align=”aligncenter” width=”578″]

Measuring how efficient a team is comes down to adjusting statistics for the number of possessions it uses. These per-possession stats can be compared between the fastest and slowest teams.

Take, for example, the 2008 Final Four, which included both UCLA and North Carolina, and these numbers from kenpom.com’s college basketball statistics database.

UCLA reached the national semifinals by playing 64.9 possessions per game, the 251st-ranked pace in the country out of almost 350 Division-I teams. The Bruins’ offense scored 113.3 points for every 100 possessions (ranking 11th) and the defense gave up 91.2 per 100 (eighth).

North Carolina had the fifth-fastest pace at 75.3 possessions per game. Its offense scored 116.8 per 100 (third-best) and its defense surrendered 95.2 per 100 (36th).

Which team was better? Neither, since both lost before the national championship game. But both styles clearly have results to suggest they work.

The Tar Heels were the flashy sports car while the Bruins were the quiet hybrid.

It’s just a matter of preference.

Twin Transformed

At the beginning of last season, UCLA touted one of the tallest teams in the country.

The thought was that UCLA could always look inside, whether it was to Joshua Smith, Reeves Nelson, David or Travis Wear, and beat opposing defenses with size. It rarely worked during a 19-14 season.

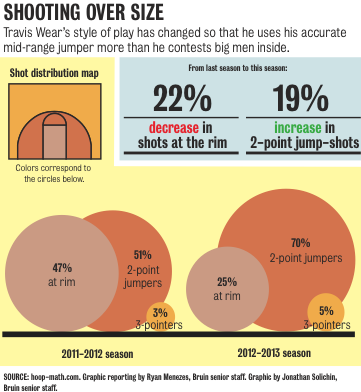

Smith and Nelson could have both been here, but are gone. The 6-foot-10-inch Wears have stayed, but now play differently.

Travis, who starts and plays significantly more than his brother, has seen his game change from that of an imposing presence to a lethal marksman.

For starters, he’s been asked to do less work inside. This season, 70 percent of his shot attempts have come on 2-point jumpers and a quarter have been layup or dunk attempts by the rim, according to data from hoop-math.com. Last season, he was spending equal time hoisting jumpers as he was trying to out-muscle big defenders.

[media-credit id=4371 align=”aligncenter” width=”361″]

[media-credit id=4371 align=”aligncenter” width=”361″]

What’s more is that Travis is making 47 percent of those 2-point jumpers, a 9 percent bump from last season.

“I think this is more of my game than last year was,” Travis said. “My brother and I are more perimeter bigs than inside bigs.”

The Wears have seamlessly fit in with this fast-paced offense. Last season proved they were ineffective at Wear-ing anyone down. Now, their talents as agile big men that can shoot have been featured.

His weapon of choice is the 16- to 18-foot mid-range jumper. It’s a shot that may infuriate some UCLA observers when his feet are so close to the 3-point line they might as well be behind it, but nonetheless a shot that opposing centers can’t handle.

There is a trade-off. With so much time spent far away from the hoop, Travis has had fewer chances to grab offensive rebounds and get UCLA second-chance points, something he was particularly skilled at last season. After grabbing 13.2 percent of all available offensive rebounds in his first season as a Bruin, he’s finding just 5.5 percent of the Bruins’ missed shots this year, according to kenpom.com.

“That’s one or two more layup opportunities when you’re grabbing offensive rebounds,” said Travis, explaining his dip in shots at the rim coinciding with his lack of offensive rebounding.

Howland now has little use for big men whose forte is bullying defenders. Smith was given just a fraction of his minutes from last season before transferring in November. Tony Parker, a highly touted recruit, hasn’t been called upon much this season either.

It seems like every UCLA team, going back to John Wooden’s days as coach, has had a guy it could count on to get an easy basket by the hoop.

Except this one.

A Balanced Act

It’s a chicken-or-the-egg kind of question: What came first? Was it the infusion of young blood? Or was it the strategy?

“That’s been the knock on us recruiting-wise: really slow basketball, coach Howland’s going to dictate tempo,” said assistant coach Korey McCray, the key to much of UCLA’s recruiting success.

“We told them if you come, this is the style we’ll play with you guys. We’ve been keeping our word with that.”

Shabazz Muhammad, Jordan Adams, Kyle Anderson and Tony Parker ended up coming to UCLA on that promise.

So far, they’ve all found their niche in the up-tempo game except Parker, who has been cast to the side as a misfit part.

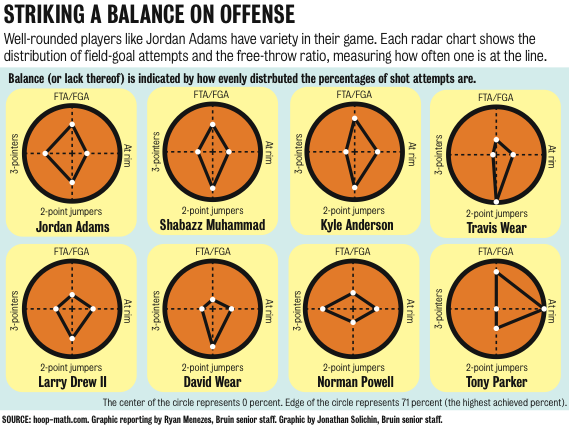

Yet for all the buzz Muhammad and Anderson get for their NBA potential, Adams has been the team’s best offensive player for a simple reason: his balance. From game one, the unathletic 6-foot-5-inch guard has shown a knack for scoring in a variety of ways.

What stands out about Adams is his ability to get to the free-throw line, whether it’s by pump-faking a defender to jump into him or a floppy move at the first sign of contact.

It’s not a flashy game but UCLA’s offense is helped by every attempt Adams, shooting a team-high 82 percent from the line, takes.

The measure of how often a scorer is getting to the line compared to his shots overall is free-throw rate, defined by free-throw attempts divided by field-goal attempts. Adams’ 43.1 is third-highest on the team. It’s better than Muhammad, who likes to settle for jumpers more, and the 6-foot-10-inch Wears, who rarely use their size to draw fouls.

[media-credit id=4371 align=”aligncenter” width=”569″]

[media-credit id=4371 align=”aligncenter” width=”569″]

Combine that with sneaky moves without the ball to get free and the accuracy of his shot, especially the way he can calmly release a jumper even when the Bruins are frantically running a fast-break, and the least ballyhooed of the freshmen is UCLA’s best threat.

“He’s just smart,” assistant coach Scott Garson said. “A lot of times you see jump-shooters and you don’t see them get to the line at all.”

Adams was always touted for his jumper. His college career has shown he does a lot more than just shoot.

Email Menezes at rmenezes@media.ucla.edu.

Very cool article. Liked the chart at the end there. Really a good way to characterize each player. Go Bruins!