An Amazonian princess named Diana abandoned her life on an island devoid of men and joined the United States in its pursuit of justice ““ the year was 1941.

She became Wonder Woman, fighting Nazis with heels, an eagle dress and a lasso of truth at her side.

She was a role model for girls in a time when readers had only known muscled men rescuing damsels in distress.

She was arguably a female counterpart to Clark Kent, complete with glasses as a disguise.

But comics no longer cost 10 cents and shops are closing left and right. As the superhero genre struggles to remain relevant, the Nazis may be gone, yet women characters in the mainstream comic business, dominated by Marvel and DC, have become increasingly sexualized.

In 1941 Wonder Woman didn’t need saving, but maybe now she does.

And maybe her savior will come in the form of other women “”mdash; women whose names are not so familiar and whose stories are part of an emerging literary craft.

Over the years, comics have diversified from capes and tights to complex and cathartic illustrated memoirs, like Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis.”

With the comic genre in flux, characters in both graphic novels and more traditional superhero comic books have evolved into stories worthy of academic study. What is the status of women in comics? Scholars and those within the industry itself can’t seem to find an answer.

From warrior woman to girlfriend

Katherine King, a professor of comparative literature, has been following Wonder Woman for much of her life. In her cozy office overlooking the sunken gardens, the woman with grey hair and years of teaching behind her said time has not been kind to Wonder Woman.

As she poured a cup of tea, King said she has watched her beloved character become increasingly sexualized.

King has taught a fiat lux on warrior women and includes scans of the first Wonder Woman in the course reader for her students.

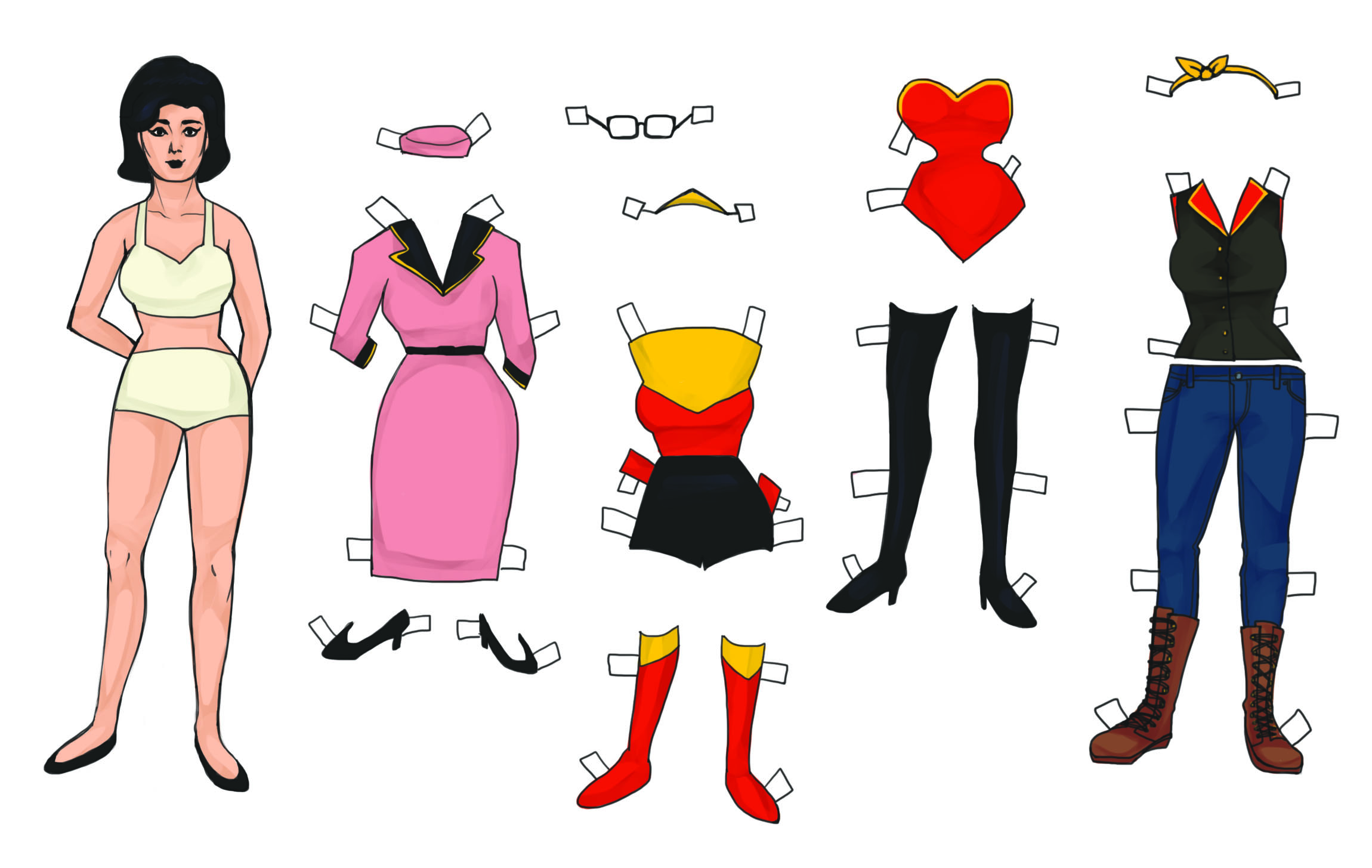

A look at the first issue shows Wonder Woman dressed in heels with determination etched on her face as she climbs ropes to reach the cockpits of helicopters flying over war zones.

The original Wonder Woman was an exception to the stereotype that women are weak or only fitting for a supporting role, King said.

The heroine was named Diana, after the Roman version of the Greek goddess Artemis.

In mythology Artemis was a protector of young girls, a huntress and a virgin. She lived in the forest with deer as her closest companions.

Although she was a superhero with super tools and skills, Wonder Woman was more real than other comic characters, like Superman, who had special abilities like flight.

That’s not to say the heroes didn’t have some things in common.

“”˜Boys don’t make passes at girls who wear glasses.’ Do they still say that?” King said, taking a minute to point out Wonder Woman’s desk-job disguise.

For such a beautiful character, Wonder Woman looks silly in glasses, King said. Glasses shouldn’t make her less beautiful, she added with a frustrated laugh. King’s own glasses can’t help but be noticed.

Wonder Woman was a beautiful but not objectified character, King said.

Her love for an American soldier did not define her, King said. It was an entertaining side story.

“There was never any sexuality,” King said. “She lived up to her name ““ virgin goddess.”

When King tried to find issues of Wonder Woman written by women to compare to issues written by men, she said she found some differences in artistic style and storytelling, but not enough to prove a trend.

Today more women may be writing comics, she said, pushing her glasses up to her face. But the publishers are still predominantly male.

Nestled between the volumes of books reaching from floor to ceiling are action figures of Wonder Woman and Xena, another warrior princess.

Publishers should recognize that young girls want to read comics like these, she said, pointing to her scans of Wonder Woman.

She said her granddaughter is a perfect example. When King introduced her to the popular television show from the ’70s, the young girl couldn’t stop watching until she finished the whole series.

In the new Justice League story line, Superman and Wonder Woman are a couple. That means Wonder Woman, the woman who never needed a man, is now, technically, “Superman’s Girlfriend.” Lois Lane? Kicked to the curb, much to the concern of fans.

With a lift of her eyebrows and a sigh, King said readers will just have to wait and see what happens to Wonder Woman in the future.

She doesn’t seem very hopeful, although she said she’d be happy to be surprised.

A genre in flux

Tara Prescott, a lecturer in the UCLA Writing Center and Writing Programs, has been reading comics since high school and over the years has seen firsthand the changes underway in the genre. For the young faculty-in-residence, the longtime hobby has manifested itself in an academic pursuit she hopes to share with her students. She also recently published a book discussing feminism in graphic novels, among other things.

Prescott’s first experience with comics was reading the popular “Betty and Veronica” magazines at grocery stores. She said she didn’t realize until she was older that Betty and Veronica spent much of their time pining over Archie, sort of the opposite of what she admires in female comic characters. Funny how it turned out.

When women do appear in superhero comics, they are often girlfriends or damsels in distress, she said. “That’s what men want to see,” Prescott said. “And when (women are) superheroes, they (are) superheroes with enormous breasts.”

Prescott said she attributes the lack of progression of women in mainstream comics to established fan bases and little desire to take risks.

Big comic companies know what sells and they aren’t going to change the formula, she said.

And if women are granted power, it seems they have to sacrifice something in terms of their names or their costumes, Prescott added.

“Heels, “˜Black Canary’ ““ they couldn’t just be badasses and be women,” she said. “They had to be some sort of bird, too.”

She said the comic shop she frequented in high school exposed her to new and interesting comics with much stronger female characters.

“I got lucky,” she said. “(The owner) didn’t treat me any different because I was a girl.”

In traditional superhero comics, many topics important to women don’t really show up, she said. It’s the small companies that can take the risks ““ the arguably growing indie comic industry.

As Prescott kneels in front of part of her comic book collection in Canyon Point, she pulls out volumes that fans of caped crusaders and dark knights may have never encountered before. She said one in particular, “Strangers in Paradise,” is dear to her heart.

Initially she said she was attracted to the art because the characters looked like more mature versions of the two girls, but then she realized they were much different.

To this day, Katchoo, the main character of “Strangers in Paradise,” is her favorite. “She’s so much tougher than I could ever be,” Prescott said.

She’s real, she added, and she doesn’t compromise anything for her toughness.

Indie comics, often self-published, serve as mediums for female authors to express themselves.

Flipping through a copy of “Are You My Mother?” by Alison Bechdel, Prescott said the American cartoonist is famous for using her comics as memoirs to explore her pain and sexuality.

The thing about comics is that they have a gutter, Prescott said. There’s a space between each block of text on the page.

In one frame an axe may be up, and in the next it may lie bloodied on the floor.

“The reader also commits the crime when they decide what happened in that white space,” she said.

That’s why comics are effective and so different from simply writing a novel, Prescott said. And she said she thinks women have more freedom to explore this art in an indie setting.

A mixed bag

A step into Meltdown Comics and Collectibles on Sunset Boulevard shows how the comic genre has changed. From the entrance it’s clear that the comic shop is not simply a superhero mecca. To the right are stacks of retro T-shirts and in the back of the store there’s a comedy club.

Who is Meltdown Comics trying to target?

“Literally everybody,” said Jake Baumgart, 25-year-old employee.

The shop is fortunate, he said, because it’s a landmark on the Sunset Strip and it attracts all sorts of people.

Baumgart, who has worked in multiple comic shops, including some in Georgia where he grew up, said traditional “brick-and-mortar” comic shops can’t maintain themselves anymore.

That’s why Meltdown Comics goes out of its way to sell a little something for everyone.

Retro board games, Star Wars memorabilia and posters are sprinkled throughout the aisles and on the walls. Next to superhero comics customers can find indie comics or reprints from newspapers.

Comic companies know they’re in a tight spot, he said. As a reader and a fan, he said he can recognize the difference in the way the companies are beginning to revisit comics.

DC, for instance, has gone out of its way recently to try to convey less-sexualized images of women, he said.

A new Catwoman figurine was deemed too sexual and discontinued. The random hole in the second-most-recent Wonder Woman’s clothes has been filled in.

The company has even hired women creators to help judge its content, Baumgart said.

At last year’s Comic-Con in San Diego, one dissatisfied reader called out the company for its “New 52″ reboot, claiming the number of female writers had dropped from 12 percent to 1 percent over the years. The exchange has since become popular in the comic fandom on the Internet.

In a July 2011 blog post addressing readers’ demands for more women writers, DC co-publishers Jim Lee and Dan DiDio pointed to established women comic artists Gail Simone and Amy Reeder, among others.

“We’re committed to telling diverse stories from a diverse point of view,” the blog post read.

Not everyone will be satisfied with the company’s attempts to improve the image of its women, but acknowledging the problem is a step, Baumgart said.

Changes to comics will be hit or miss, as always, said the avid fan of Robin in a graphic T-shirt and black-rimmed glasses. But fans will continue to read to see what happens next.

He isn’t giving up on comics.

Unanswered questions

Wonder Woman and Persepolis’ Marji are simply women of different worlds and words. Neither is on her way out, nor are they in a tug-of-war. The counterparts are thriving, complementing different audiences as the genre finds its balance.

So to ask about the status of women in comics, it seems, is also to ask, what one means by “comic.”

The answer to both questions is somewhere along the lines of “to be continued.”