Still in its development phase, “Dog Nose Knows” is a visually interactive board game that allows a player to experience the life of a dog. The photo cover for the game features the nose of an Irish dog named Zeb, who is known for singing and howling whenever music is played.

The original version of this article contained an error and has been changed. See the bottom of the article for additional information.

The room was crowded, and serious faces looked to Jonathan Ong as he asked a key question.

“If I urinate on a spot, does that mean no one else can take it?”

This question may seem humorous, but the rationing of urine to mark territory is no laughing matter to a canine, and on the night of Nov. 1, that’s exactly what Ong was.

Ong, a first-year computer science and engineering student, was one of many students who took on the role of a hunter dog to play test “Dog Nose Knows,” a board game themed around a dog’s sense of smell. This game integrates strategy, memory and a good amount of luck to present a dog’s smell-driven world in a visual, interactive format.

“I was trying to balance strategic elements and memory in a family-fun game,” said Adeline Drucker, the game’s designer who works with the UCLA Game Lab.

Still in its development phase, “Dog Nose Knows” will be presented and play tested on a larger scale today in the Harvestworks Team Lab in New York, New York.

“Dog Nose Knows” emerged as an exhibition called the “Sniffing Booth” during a dog symposium titled “Made for Each Other? Dog and Human Co-evolution,” held by UCLA’s Institute for Society and Genetics in February 2011. Conceptualized by UCLA Design | Media Arts professor Victoria Vesna, Columbia neuroscientist Siddharth Ramakrishnan and designed by Drucker, this project has made a long transition from a science exhibition to the artistic board game it is today.

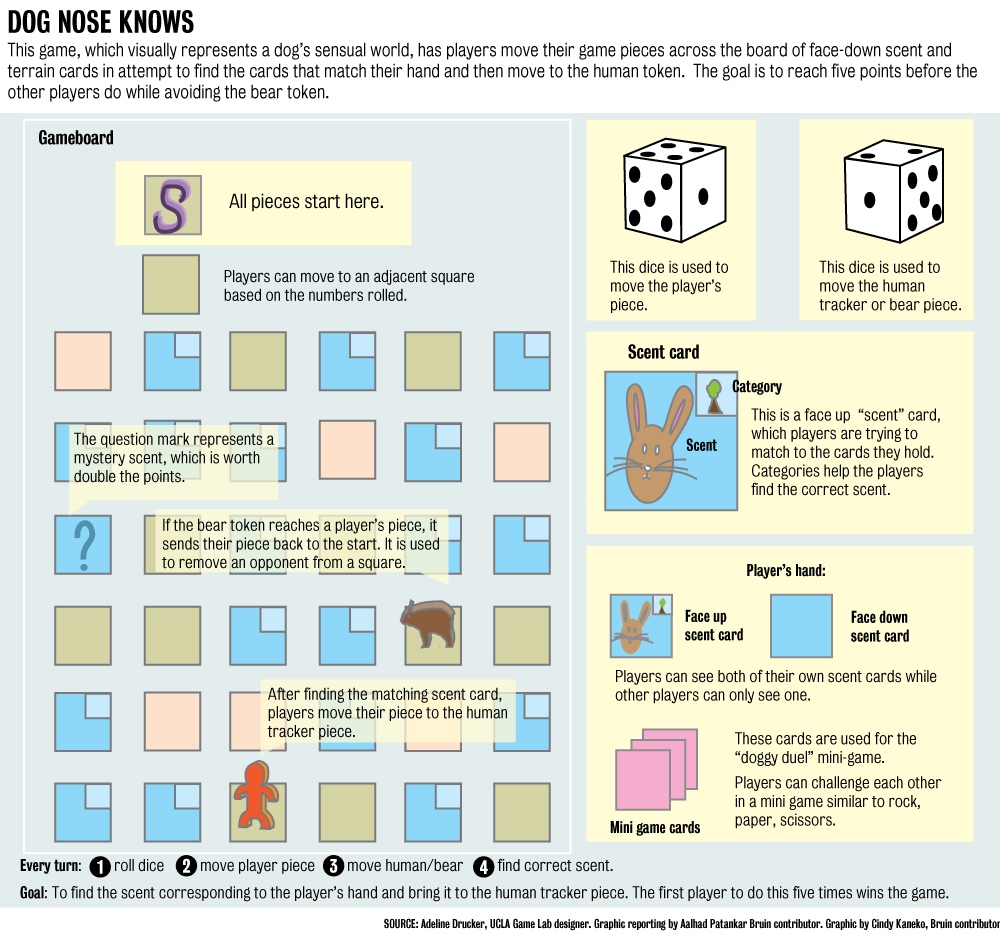

The goal of this game is simple: to track down scents in a forest and return them to a human tracker. Players do this by moving their pieces using a dice to uncover, or “sniff out,” scent cards on the board that match the ones in their hand.

Added dynamics introduce new twists to the game, such as a dangerous bear piece, which can be moved by any player to send another player back to the start, and a bonus mystery scent that every player looks for. These features add new dimensions to the game by allowing players to strategize, bluff and even sabotage their way to victory.

Players truly become canine as they experience real aspects of a dog’s lifelike obedience, territorialism and social hierarchy by using their game piece to sniff out hazardous scents, urinate on spots to mark them as theirs and challenge other players to “doggy duels,” a rock-paper-scissors style mini-game.

“A dog’s sense of the world and experience with the world is so different from that of humans. One of the main goals of this game is to understand this difference,” said Ramakrishnan, the scientist behind this arts and science collaboration.

Ramakrishnan’s research has provided the backbone for “Dog Nose Knows,” despite a surprising fear of his.

“I’m scared of dogs, I’m really scared of dogs. If a dog walks in the room, I’ll be standing on the desk,” Ramakrishnan said. “Presenting in an emporium surrounded by dogs has really broadened my world.”

His interest in the umwelt, the environment of an animal perceived by its senses, is one of the main inspirations behind this project. By having players search for scent pieces indistinguishable to a human’s nose, such as rabbits and landmines, this game demonstrates the power of a dog’s sense of smell and creates a visual representation of a dog’s umwelt.

The design and artwork of “Dog Nose Knows” takes shape through Drucker’s artistic rendition of what a dog’s smell might be seen as. The comic-style drawings on the game cards and the odorous effect caused by a hazy graphic design, keep the artwork simple enough so as not to distract players, but alluring enough to catch their eye.

“Dog Nose Knows” was play tested in the Broad Arts Center on Nov. 1, an event which drew Ong and many other gamers, dog lovers and students actively looking to get involved with the project. One such student pulled out his own model game board to suggest a possible improvement to the game’s design, while another, third-year computer science student Alex Groff, said he plans to make his contribution by helping develop an online version of “Dog Nose Knows.”

“This game is constantly changing,” said Vesna, who hosted the UCLA play test in hopes of getting student feedback. Many of these changes, such as the addition of the dangerous bear piece and the “doggy duel” mini-game, are now an integral part of the gameplay.

Vesna, Ramakrishnan and Drucker are still looking to further incorporate features from the sensory world of a dog into the game.

“Dogs can smell in time; that would be an interesting mechanic to add to the game,” Drucker said.

As the Harvestworks game test approaches, the creators of the game reflect on the long journey this project has taken and how much they have learned from it. “Smelling is a much deeper experience for dogs. They can smell emotion, they can smell cancer,” said Drucker.

Whereas this project has helped Ramakrishnan become more comfortable with dogs, it has deepened Vesna’s understanding and connection with dogs. Vesna, a dog lover, has spent time with and taken pictures of dogs around the world for this project.

“I want this game to personalize dogs, and bring people closer to them,” said Vesna. “I picture a family sitting around, talking and playing and learning about animals, and I see dogs as part of this picture and family.”

Here is an explanatory graphic of the game:

Correction: Jonathan Ong’s name was misspelled.

Great article! I love the wacky, yet creative concept of the game.

“Whereas this project has helped Ramakrishnan become more comfortable with dogs…” hahahahahaha

Interesting game… Might consider getting this for my pets.

Thank you very much for the feedback!