A man and a woman make their way through the streets of Philadelphia, divided by patches of intense sunlight and the shadows cast by tall city buildings.

The sharp contrast between the two figures and the light and darkness make this composition appear perfectly planned.

But for American photographer Ray K. Metzker, this scene was captured on film in just one click.

This photograph, along with nearly 100 of Metzker’s other works spanning his five-decade career, is on display in the Getty Museum’s The Photographs of Ray K. Metzker and the Institute of Design” exhibition.

The Getty Museum has collaborated with the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Mo. to curate the exhibition, which also includes photographs taken by Metzker’s peers and professors at the Institute of Design in Chicago.

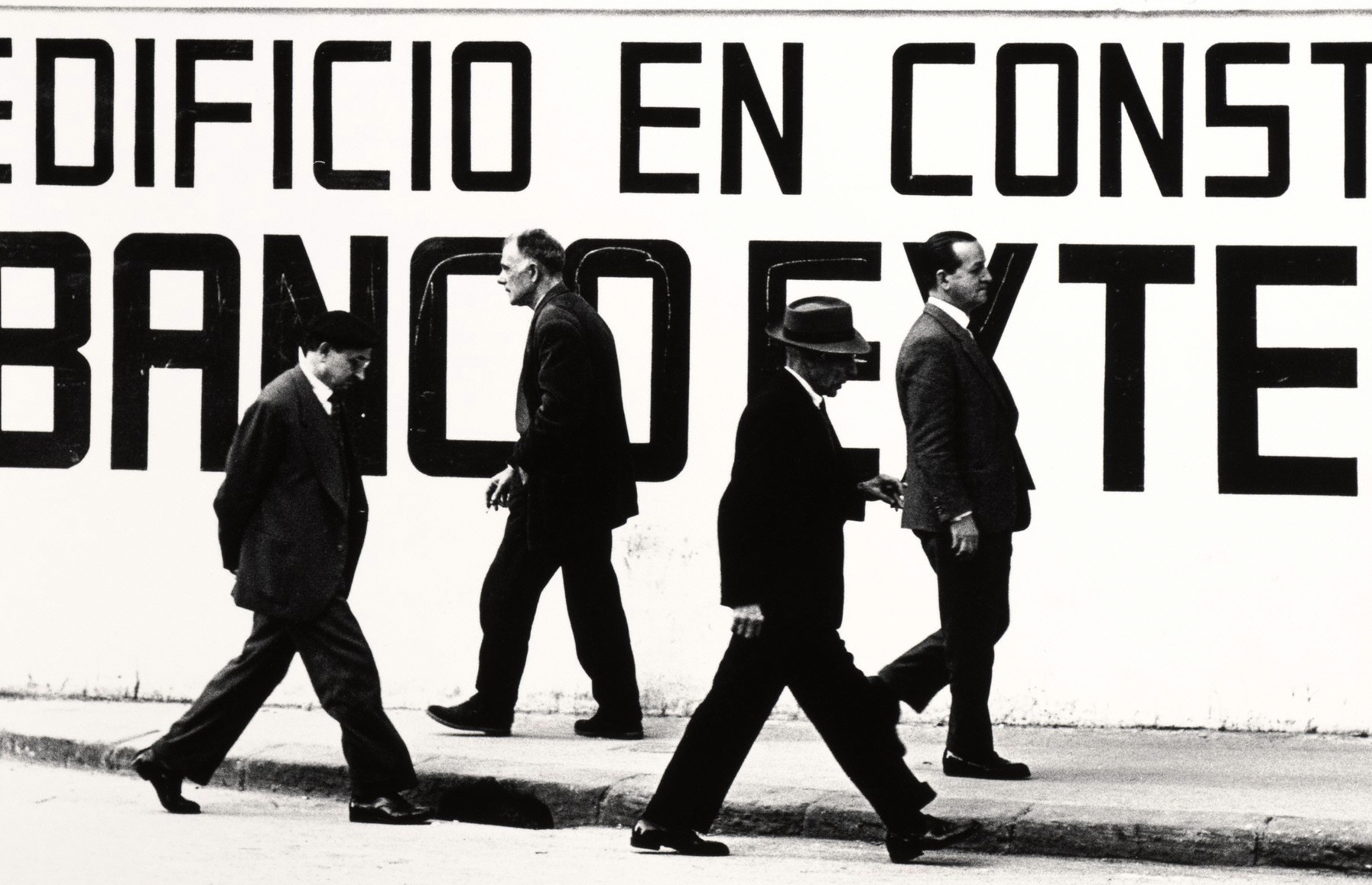

“(Metzker has) an interest in people, … the theater of the street (and) the idea of the stage. … This whole notion of the stage, of lighting, of individual figures as both real and symbolic, all those threads are evident in (his) work,” said Keith F. Davis, senior curator of photography at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Davis co-curated the exhibition, which is organized by Metzker’s collections and projects through the years. In collections like “City Whispers,” Metzker documented daily city life on the streets of cities like Los Angeles and Philadelphia. Other sets depict street life in Chicago, Europe, New Mexico and Atlantic City, N.J., as well as Metzker’s experimentation with landscape and composite photography.

Davis said Metzker developed a strong formal background in photojournalism, shooting lecture and sporting events for his high school and college publications. Metzker later experimented with abstract, avant-garde photographic techniques, an interest that was most likely piqued by his studies at Chicago’s Institute of Design from 1956 to 1959. The school was named the New Bauhaus, after the German Bauhaus craft and fine arts school.

“The (Institute) was totally about … balance: being attentive to sociological facts (and) what the real world is about … but also becoming fluent in the language of the medium,” Davis said. “What does (photography) do that no other picture medium can do?”

Metzker found his experimental niche in capturing images with sharp, high contrast, found in the scene of the man and woman walking in Philadelphia, as well as in using selective focus to shift the subject of a photo and taking multiple exposures to create couplets and layered composite images.

One segment of the exhibition, titled “Composites,” displays large works created by taking overlapping exposures on only one roll of film as opposed to enlarging smaller snapshots. Davis said this technique placed Metzker on the international radar for its complexity.

From a distance, these photos appear to be an abstract, mismatched collage of photographs.

Upon closer inspection, however, one can see clear details of scenes from daily city life in each vignette. Rows of photos of subway riders ascending and descending a stairway are repeated in one work. In another titled “Comings and Goings,” Metzker captures the bustle and chaos of blurry, almost translucent, crowds going through a large commercial doorway.

The second portion of the exhibition focuses on the works of Metzker’s photography instructors, including Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind, and thesis projects by his peers from the Institute of Design.

Virginia Heckert, curator of photographs at the Getty Museum, said these photographers, like Metzker, delved into innovative techniques and styles. They placed simple objects in complex surroundings and focusing on found objects, subjects that were not normally considered to be art.

“The New Bauhaus emulates the spirit of the Bauhaus: (the) desire to combine art and craft,” Heckert said. “(It taught) this very open, intuitive experimentation with the basics of the medium.”

For Siskind, this experimentation led him to focus on found objects. His photos of close-up views of tar stains, torn posters and paint peeling off walls border on abstract expressionism.

Callahan, meanwhile, took a different approach on portraiture. He often photographed his wife Eleanor extremely close-up with white light or shot her from a distance against a landscape background.

Kenneth Josephson, who graduated from the school in 1960, experimented by moving the camera during an exposure to give his landscape photos a feeling of animation. Charles Swedlund, another thesis student, created multiple exposures, layering different images on top of another. In one photograph, the outline of a window frame is superimposed on the silhouette of a nude woman.

Arpad Kovacs, assistant curator of photographs at the Getty, said graduate photography student Joseph Jachna focused on capturing something as simple as water for his thesis project.

“What’s really interesting about Jachna’s project is to take this focused subject of water and really explore the photographic possibilities of (it),” Kovacs said. “He’s captured reflections, different tonalities of light shining onto water. … He (was) fascinated with this idea of what water can create on film.”

Davis said that for Metzker, much of this fascination with what film can capture is not in what he intends a photograph to mean.

“(Metzker) is intuitive enough that he’s never going to say “˜This picture is about x, y and z,” Davis said. “(The photos are about) the visual impact and the reading that each viewer takes away.”

Email McQueen at jmcqueen@media.ucla.edu.