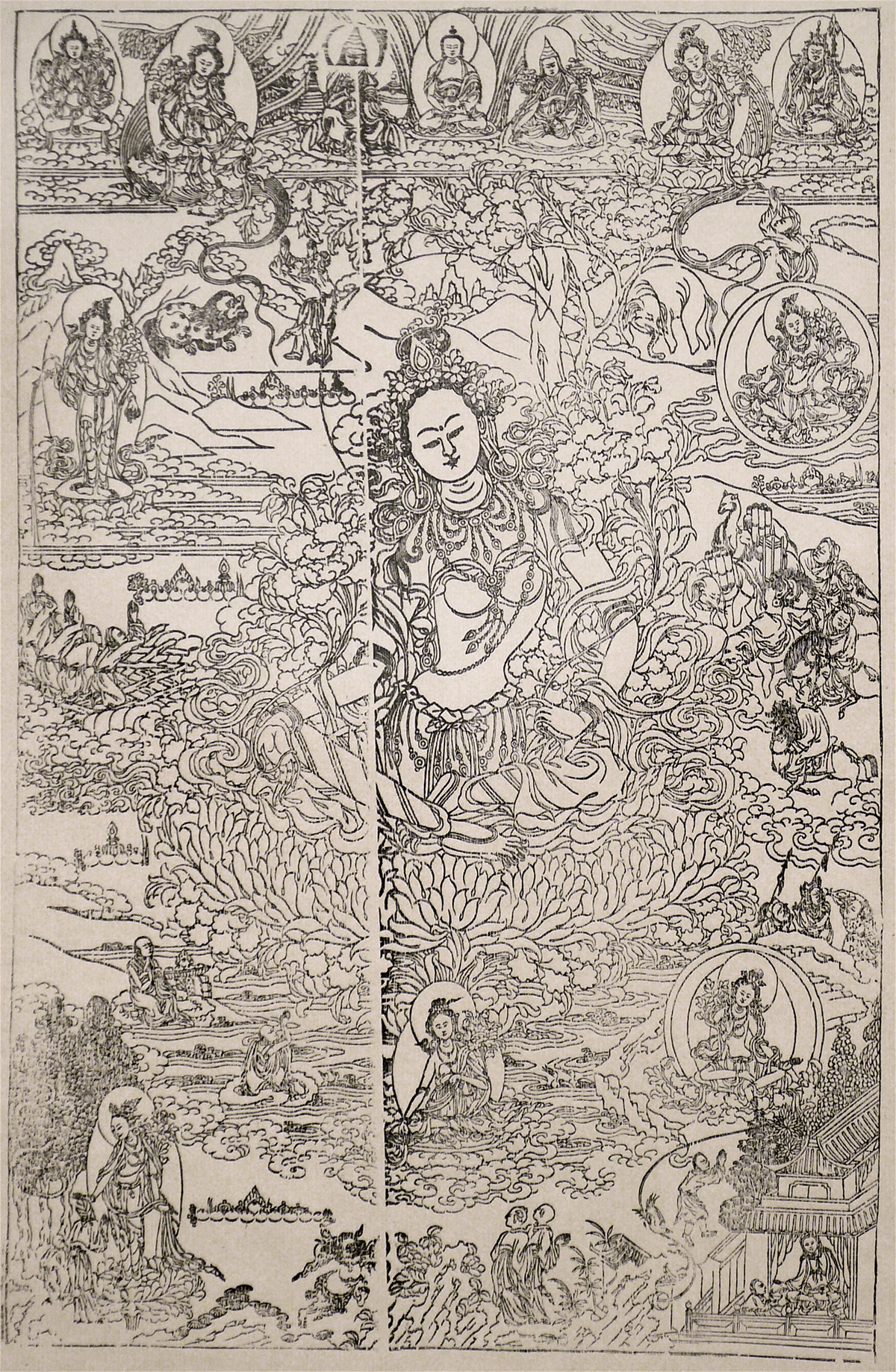

Stark black ink against aged yellow paper swirl in smoky twirls to depict the ringlets of hair weaving in front of a wise round face, the swaying motion of his meditative posture and the petals of a large illustrious flower cradling the round-faced bodhisattva, an enlightened being. At first glance, the stark lines seem to have been guided by a skilled pen, but with careful observation the flawless details reveal a deeper secret.

The “Green Droma” is one of the many illustrative woodblock prints found in the “Pearl of the Snowlands: Tibetan Buddhist Printing from the Derge Parkhang” exhibition in the Fowler Museum. High in the Himalayan Mountains, locals of the Buddhist Tibetan city of Derge gather to make paper, ink and hand-carved woodblocks into religious literature and images within the walls of the Derge Sutra Parkhang holy printing house.

“The Parkhang is a really important institution to the Buddhist people of Tibet. … It really is a pearl,” said curator and UCLA alumnus Patrick Dowdey. “People think of it as a treasure house.”

Between 2004 and 2007, Dowdey and photographer Clifton Meador collaborated to learn the cultural significance behind the Parkhang and attempted to describe the consequential impact on the local people. On Saturday afternoon, Dowdey held a lecture at the Fowler Museum in which he shared his discoveries and emphasized that the woodblock prints are not only beautiful but also hold a deep spiritual significance to the people of Tibet.

In his lecture, Dowdey presented more images, videos and personal accounts of the people he met in Derge ““ some of them of men with old leather faces and missing yellow teeth. He created a guided tour of images down the main street of Derge, past modern shops with modern technological innovations and up to the printing house where the modern world halts.

Founded in 1729, the Parkhang is the only surviving print house from the cultural suppression by the Chinese from the mid-’50s to late ’70s. This is because it was protected by the local people from the Red Guards, military agents of the People’s Republic of China movement under Mao Zedong.

“The Parkhang became the center for reinvigorating the traditional Tibetan Buddhist culture, … (and today) every Tibetan knows of this place,” Dowdey said.

With its reopening in the late ’80s, Dowdey said that the Parkhang recreated many of the lost religious texts to the monasteries, and the printing house now serves as a site for tourism, pilgrimage and the celebration of Tibetan Buddhist culture. Despite the laser printing shop about 100 meters away from the Parkhang, the books printed by woodblock are considered the most valuable and the most accurate versions of the religious texts.

Other prints lining the main hall of the exhibition vividly recall stories of history, the Buddha, sutra (Holy Scripture) and cosmology. A 25-minute video following the laborers of the printing house show how they make paper, ink and the woodblocks.

The video shows woodblock craftsman Dawa Tsering with squinting eyes carving out the thin and swirling strokes of a complex passage. With tiny chisels, he says that he must be very precise because once he finishes, he knows that this block will be used for generations after him, just as they have used blocks from generations previous.

A clear split down the center of the final piece featured at the exhibition hints at the age of the print. Carved back nearly 300 years ago, this pearl of an antique print will continue to be used by many generations to serve as an example of fine woodblock craftsmanship.

Compiled by Brigit Harvey, Bruin A&E contributor.