Twisted, nude women with long, flowing hair float on thin streams of water, the fluidity of their bodies matching that of their aquatic surroundings. A large fish with etched scales swims alongside them as their bodies float off the page.

This image, titled “Fishblood,” is one of more than 100 of the late Austrian artist Gustav Klimt’s sketches and drawings on display in the J. Paul Getty Museum’s “The Magic of Line” exhibition. The Getty Museum has collaborated with the Albertina Museum in Vienna to curate the exhibition, which shows several of Klimt’s works that have never been displayed in North America, in celebration of his 150th birthday.

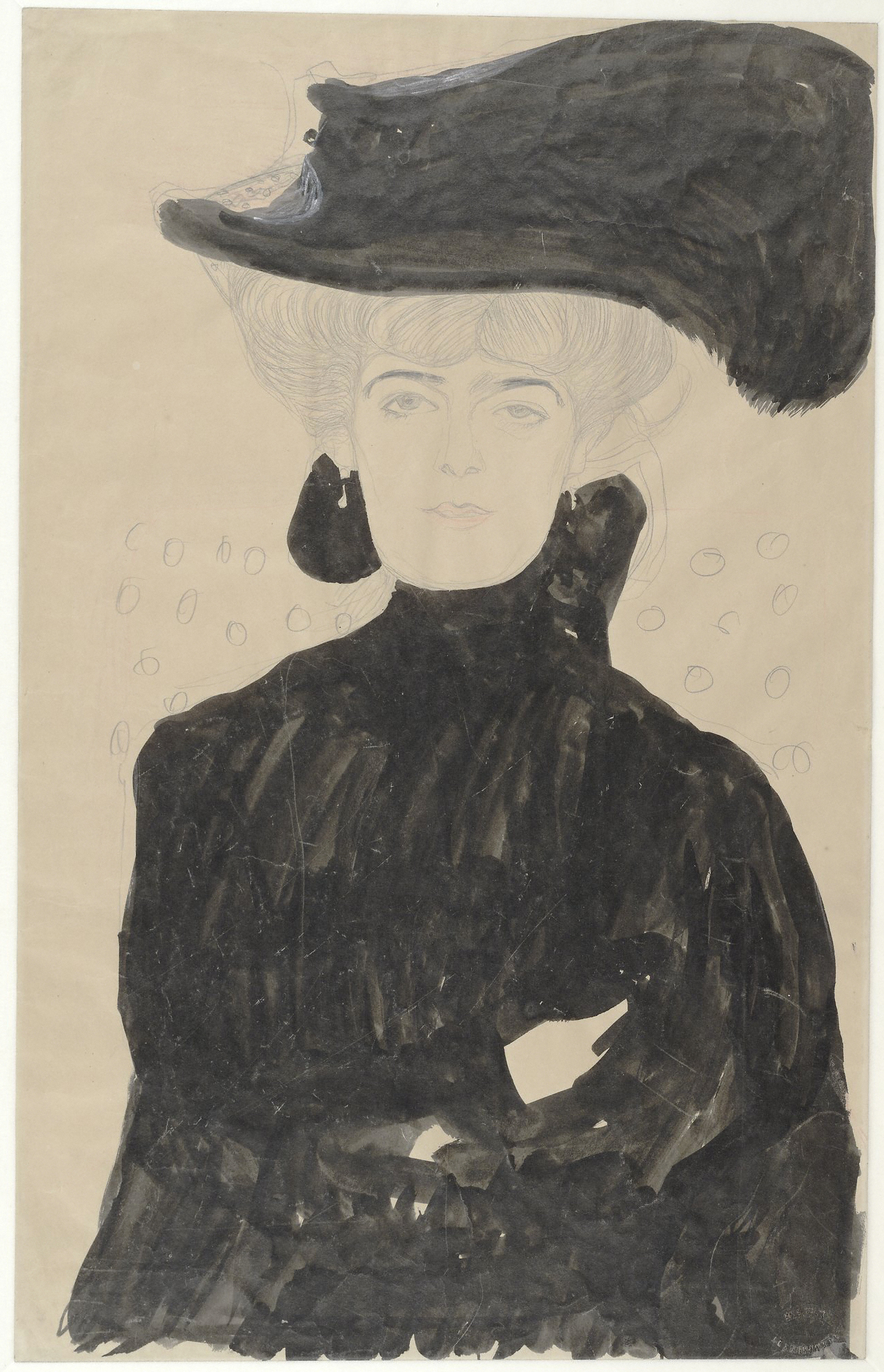

Lee Hendrix, the senior curator of drawings at the Getty, said the exhibition chronologically traces Klimt’s progression from a conservative to modernist artist. Klimt is well known for his ornate, gold paintings such as “The Kiss,” a work depicting two embracing lovers in gilded robes, but this selection of artworks is meant to reveal his talent as a draftsman, an artist who creates detailed drawings.

“Klimt is an artist that we think we all know,” Hendrix said. “We grew up with the college dormitory posters of “˜The Kiss,’ (but) the way we (should) know him is through his drawings.”

Hendrix said the exhibition highlights Klimt’s interest in the feminine form and human body, as the sketches were drawn from live models. Floating, nude female bodies such as those in “Fishblood,” embracing lovers, and scenes of masturbation and lesbian love are central motifs in many of the displayed works.

Klimt relied on conventional techniques, such as using light and shadow to create realistic 3-D forms in his early works, Hendrix said. However, he also later experimented with avant-garde Symbolism, a movement in which artists explored different psychological states of the mind and reality in their art.

Marian Bisanz-Prakken, the curator of drawings at the Albertina Museum in Vienna, said Klimt experimented with Symbolism by representing subjects in unconventional ways. For example, in “Medicine,” Klimt created a visual allegory to embody his idea of medicine through a work in which a swirl of nude women and a skeleton engulfed in smoke float into the heavens.

“Allegories of the sciences were commissioned by the University (of Vienna), and they expected some … vision of the positive effect of the sciences on mankind (from Klimt),” Bisanz-Prakken said. “But he did something totally different. He represented mankind as a stream of naked people flashing by in the cosmos. … He had a totally new approach.”

The exhibition also includes a model of the “Beethoven Frieze,” a plaster mural that Klimt painted for the Vienna Secession, an art association that aimed to stray from conservative artistic style, to honor the composer Ludwig van Beethoven. The gallery at the Getty Museum includes sketches used as models for the actual painting and a replica that wraps around the walls of a room.

The frieze, a horizontal row of imagery, depicts different stages of mankind’s struggle for happiness in human forms. A gaunt couple who represent the weakness of humanity beg a knight in gold armor and his female companions, Compassion and Ambition. Sultry women with piercing seductive eyes personify Lasciviousness, Wantonness and Intemperance, and a skeletal woman represents Gnawing Grief.

This dramatic imagery culminates in a depiction of the arts and a positive outlook on life. Poetry, a golden-robed woman, reads a book, and a chorus of angels sings in paradise. The final scene of the frieze contains two lovers embracing under a gold-leafed sun and moon.

Edouard Kopp, assistant curator of drawings at the Getty, said the frieze effectively demonstrates Klimt’s transition from his earlier conservative style.

“What’s interesting about many of the drawings in this gallery (is) how stylized they are. Although they are life studies, they take some distance and simplify forms,” Kopp said. “These figures are meant to be fluid, ethereal figures. … The draperies are also very stylized (but) you can still feel the body beneath that.”

The exhibition concludes with sketches that define Klimt’s personal modernist style. While the subjects of these sketches are still nude women engaged in sensual acts, Bisanz-Prakken said these works demonstrate a final shift in his style. The figures are flat and lack shading, and the lines themselves are broken, loose and no longer as smooth as they were in his earlier conventional works.

“Every line is an adventure,” Bisanz-Prakken said. “(Each time) you go into the lines of his drawings, … you see different things.”