High on a mesa overlooking a nude beach was an archaeological hot spot.

Old bunkers constructed out of fears of invasion during World War II shared the farmland earth with remnants of Native American tribes, all at an unlikely location ““ the UC San Diego chancellor’s residence in La Jolla.

Yet, the Native American findings should not be surprising.

Tribes inhabited the La Jolla area for nearly 10,000 years and their presence was found throughout the UCSD campus. Each time construction workers broke ground on a campus walkway or staircase, they would encounter Native American artifacts.

Sometimes, there was more.

On an August evening in 1976, UCLA professor Gail Kennedy’s team of anthropology students discovered two human skeletons near the chancellor’s swimming pool. The pair ““ an older woman and a younger man ““ was buried together, two meters down in the soil, with one facing the ocean and one facing inland. Scientific dating techniques proved them to be more than 8,000 years old, making the couple the oldest multiple burial in the New World, Kennedy said.

Now decades later, the skeletons have resurfaced in news reports for their place at the center of a current legal dispute between UCSD, a local Native American tribe and a group of three UC anthropology professors about the role culture should play in scientific research.

The discovery

Kennedy had just moved from her position at California State University Northridge to UCLA when she decided to organize a field school in San Diego for her former and soon-to-be anthropology students.

Though she normally focuses on early human research in Africa, Kennedy taught the field school in La Jolla because of the location’s multitude of artifacts and its need for a local archaeologist, she said. The team set up camp at University House, the UCSD chancellor’s residence. The chancellor planned to make additions to the home, but based on the number of artifacts found in the area, a team of archaeologists was first required to do a dig.

It was there that Kennedy’s team made its discovery. The male and female skeletons were bunched together with his feet on her head, a possible indication of their being bound.

Under the excavation lights, the team exhumed the skeletons from their double grave using a plaster jacket, an archaeological technique usually reserved for heavier animal bones. Because of time constraints, the team put a box around the bodies, poured plaster into the crevice, and lifted the pair from the dirt.

“We treated them as you would treat any precious skeleton,” Kennedy said.

Upon closer inspection, Kennedy’s team noticed some distinct characteristics.

The man’s thumb knuckle was attached to his chin and his detached ring and middle fingers were found in his mouth. The rest of his hands were found between his knees. The “why” is yet to be determined.

Even more mysterious is the fact that the same piece of both skeletons’ skulls was missing. The pieces, which would have fit on the right side of the head, were never found, Kennedy said.

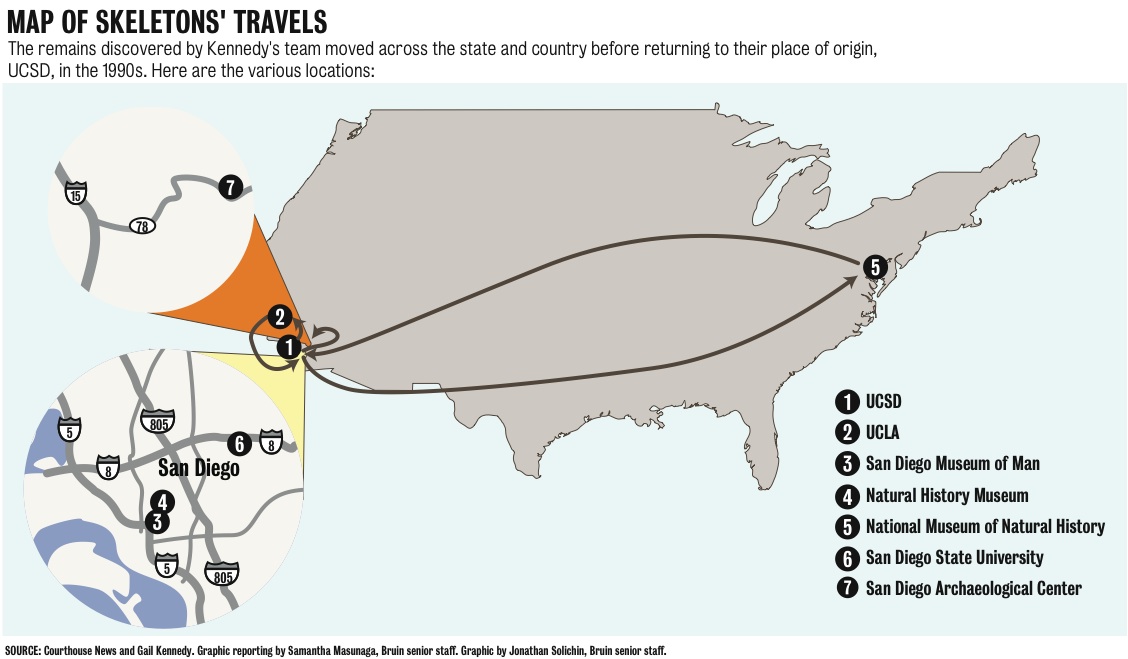

After the conclusion of the field school, Kennedy took the skeletons back to UCLA, where they were studied and subsequently shipped to various museums before returning to Westwood.

NAGPRA in the 1990s

The advent of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, marked a change in anthropological research. Passed in 1990, the federal law mandates that all Native American cultural items, including remains, funerary objects and sacred items, be returned to lineal descendants and culturally identifiable tribes. The new law affected all federal agencies, including museums and universities that might have received federal funds.

Reactions among researchers were mixed.

“Some people were really resistant, some thought it was time (for this act to be put in place),” Kennedy said. “Most thought there should be a balance, like me. We should be able to study these ancient remains, but do it with respect.”

The new federal law directly affected Kennedy’s lab. Her research was not interrupted, but she had to send the skeletons back to their place of origin, UCSD, and catalogued the remaining Native American artifacts in her lab, in accordance with government mandates. Then, the items were placed in Hershey Hall along with other NAGPRA eligible artifacts from the biology department and the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, so that tribes could come and claim them.

But that never happened ““ at least not right away.

“We thought that Native American tribes would be standing in line to get (the artifacts),” Kennedy said.

In fact, the first instance of a tribe coming to claim ancestral items at UCLA was in 1998 ““ eight years after NAGPRA went into effect ““ when representatives from the Hopi nation came to Westwood to repatriate remains of their tribe.

Most recently, a woman’s jawbone was reclaimed in March by the Wiyot tribe, located near Eureka, Calif., according to Daily Bruin archives.

The lawsuit

A claim for the skeleton couple found by Kennedy’s team came to UCSD in early 2000 from the Kumeyaay tribe.

The tribe legally battled the university for repatriation of the remains for years, as controversy swirled over whether the skeletons could be culturally identified to the Kumeyaay, said Dorothy Alther, an attorney with the California Indian Legal Services representing the Kumeyaay in their lawsuits. But after a clarification to NAGPRA law in 2010, which specified that remains that could not be culturally identified had to be turned over to the tribes on whose aboriginal lands they were found, the tribe tried again.

Since the bodies were found in the Kumeyaay’s aboriginal lands in San Diego County, the group asked the university to return the remains to the Kumeyaay Cultural Repatriation Committee, an organization specifically dedicated to repatriation efforts, Alther said.

The university initially agreed, but had to undergo an internal consultation with the UCSD chapter of NAGPRA and the UC-wide NAGPRA committee. While the majority of committee members favored repatriation of the remains, two professors spoke out against it, questioning whether the remains were indeed of Native American descent, Alther said. If the remains were not Native American, NAGPRA would not apply.

While dietary studies of the skeletons and knowledge of Kumeyaay cremation traditions have led to mixed scholarly opinions on whether the remains are Kumeyaay ancestors, this particular comment was surprising, Alther said.

“This issue (about whether the remains were Native American) had never been raised before in the 10 years we worked with the university,” she said.

In the end, the UC committee supported the return of the remains and the repatriation process began ““ until the university got wind of another lawsuit.

The two professors from the committee and a third anthropology professor filed a temporary restraining order to prevent the transfer of the skeletons in early January.

Professors Tim White of UC Berkeley, Robert Bettinger of UC Davis and Margaret Schoeninger of UCSD, who filed the most recent lawsuit, refused to comment on the case. But in a letter published in Science Magazine in May 2011, the professors said the return of the remains could affect knowledge of the “peopling of the Americas and the antiquity of coastal adaptations.”

Their lawyer, James McManis, also refutes the Native American ethnicity of the remains.

“There’s just no scientific basis, no rational basis for the claim,” he said. “(The professors) are all really concerned scholars that believe that these remains should be made available to their colleagues for research.”

For now, the transfer and lawsuits remain in limbo, as further litigation continues to be filed. UCSD could not be reached for comment about the lawsuit.

Though discussion has been heated on both sides, Kennedy said she has stayed out of it. In fact, no one has contacted her throughout the litigation for her opinion or her story, something she said she is happy about.

Today, the 30-year veteran in her field is working on a book titled “Origin!” which describes the rise of genus homo. She rarely travels to San Diego, and doesn’t often think about the double discovery, which she contends is Native American.

But she does have thoughts on the conflicts between researchers and tribes.

She said NAGPRA could be a way for tribes to gain a political voice, when they had none. She added, however, that she didn’t think the researchers were the culprits.