The Higgs boson, known commonly as the “God particle,” is thought to be responsible for all of the matter in the universe. But physicists only announced evidence of its existence last week.

From Royce Hall to far-flung galaxies, most things owe their own existence to subatomic interactions with the Higgs field, which permeates the entire fabric of the universe. Without the field, the teeny- tiny particles that serve as building blocks for everything else would, theoretically, never have stuck together. No Higgs, no mass, no nothing.

Physicists at the European Organization for Nuclear Research ““ or CERN ““ the laboratory famous for the world’s largest particle accelerator that straddles the French and Swiss border, announced Wednesday that they are 99.9999 percent sure they have found a new particle ““ a type of boson.

“It was a milestone day,” said Robert Cousins, a UCLA physics professor and collaborator on the Compact Muon Solenoid project, one of the two experimental groups to announce the Higgs boson findings.

Cousins, along with fellow UCLA physics professors Jay Hauser and David Cline, spent significant portions of their last five years in Europe working on technology that allows scientists to detect particles millions of times smaller than a period on a page.

All three are key members of the UCLA CMS group, which designed and built hundreds of chambers and triggers for an enormous underground detector. These detectors looked for the resulting products of the Higgs boson: tiny particles called muons, which themselves only live fractions of a nanosecond.

“Not everyone was working (directly) on the Higgs, but it’s definitely been a priority,” said Chris Farrell, a doctoral candidate in physics. “We wanted to discover the Higgs in as short a time as possible.”

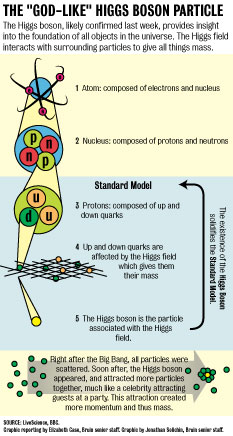

Physicists are excited about the new particle because it looks distinctly like the subatomic particle predicted more than five decades ago by a theory called the Standard Model of physics, according to news reports.

The Standard Model describes the fundamental interactions and elementary particles that form the basis for the universe ““ like the electron, which is the negatively charged particle in an atom.

The Higgs boson is unique, and is key to the theory: Scientists say it proves the existence of the Higgs field, which is part of the reason why other particles have mass.

“Newton explained mass in the 1600s. … Here we are, over 400 years later, finally beginning to understand what it is,” said David Saltzberg, a UCLA physics professor.

Saltzberg compared the Higgs field to a universe-sized ocean. It is fluid, for the most part, but when scientists shake it up by adding enough energy, they can separate some of the “water droplets” ““ Higgs particles ““ from the ocean and detect them.

“The most amazing thing about the Higgs particle is not the particle itself. It’s just evidence of something bigger,” Saltzberg added.

The existence of the Higgs boson would largely help explain what mass is and where it fundamentally comes from, he said.

Cousins cautioned that the announcement is not proof of the Higgs boson, but rather encouragement to run more experiments and analyze more data.

He related the hunt for the Higgs boson to looking for someone lost in the countryside. The search party ““ high-energy physicists ““ figured out which field to look in, and have spotted the missing person. With the knowledge that the Higgs boson is the only person who is supposed to be in the field, physicists are pretty certain they have found him. But scientists have yet to “shake hands” with the missing man, so they cannot positively identify him yet.

There is a chance that the particle discovered is not the Higgs boson, or, possibly, only one of the Higgs bosons ““ there could be up to five. But many scientists think it is unlikely.

“There are alternatives, but they’re really wild alternatives,” Cousins said.

However, Cousins and Saltzberg said scientists are also hoping the man in the field is a little out of the ordinary.

“It would be disappointing … if (the data) fits in exactly to the Standard Model,” Cousins said. “Everyone believes there are particles and forces beyond the Standard Model … but we need clues as to what comes next.”

The next step for UCLA researchers like Saltzberg and Farrell is to build even better detectors and triggers to search for even more new particles.

“We’re just getting started. We’ll go wherever the experiments lead us,” Cousins said.