Surrounded by bags of sand and tangled wires, five pairs of hands smoothed cement over what appeared to be a giant pot.

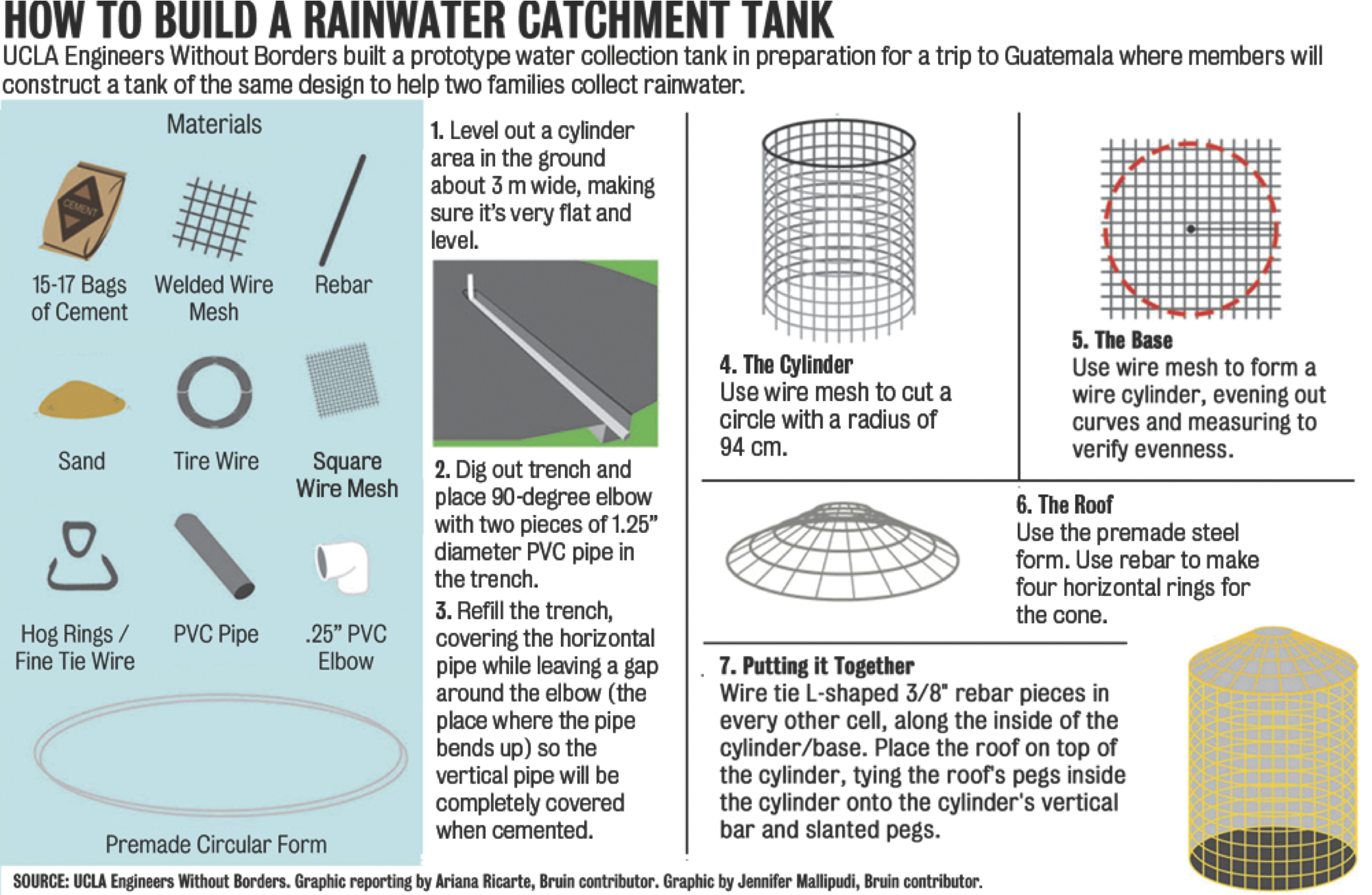

Members of the UCLA chapter of Engineers Without Borders, an organization that aims to connect engineers with sustainable projects worldwide, have been building a water tank prototype that collects rainwater for everyday use since the beginning of this quarter in Sunset Canyon Recreation Center. Seven members of the club, all undergraduate students, are currently in Chocantariy, Guatemala to rebuild the tanks using materials from the region.

The members of the group hope to help the residents of Chocantariy, a region in northwestern Guatemala lacking access to indoor plumbing, gain access to clean water, said Tony Antich, a civil engineer who volunteers as a mentor for UCLA’s Engineers Without Borders.

A representative from the United States works in Guatemala to identify the needs of the community, Antich said. The representative then selects families that will receive the tanks based on need.

During their stay in Guatemala, the engineers will build two 5,000-liter water tanks outside of people’s homes. They will then attach the tanks to gutters on the roof to collect rainwater which will be used for cooking and cleaning.

Building tanks in the United States is a relatively simple process. Construction in Guatemala is a different experience, said Brandon Lanthier, a recent graduate in civil engineering and project leader. The mountainous environment and more rudimentary tools are some of the different aspects of construction that the students must get accustomed to.

For example, instead of using ladders to navigate around the tall tanks, the engineers typically use ropes and wooden scaffoldings tied in the trees.

Women and children must make several trips to a river to gather the water they will use for day-to-day tasks, a process that takes about an hour during the rainy season, Antich said.

But during the dry season, residents have to wake up very early and find a place in the river that’s not dried up. This takes about 30 percent of the day.

Once the tanks are completed, rainwater will be collected in the tank. It can be removed through a faucet attached to the bottom of the tank. Then, the water is poured through a clay filtration system and boiled before it can be used for cooking and drinking, Lanthier said.

The two families receiving the water tanks will contribute to the project by working alongside the volunteers and providing lunch.

UCLA Engineers Without Borders chose to design the water tank after models similar to ones made by the Peace Corps several years ago because they seem to have been reliable over the years, Antich said.

Members of the organization did, however, modify the older designs to accommodate the different environments. Their design was approved by the national chapter of Engineers Without Borders, giving them approval to move forward with plans.

The students use local materials to construct the tank, Lanthier said, scooping wet cement into a tin pan.

In addition to the volunteers and community members, professional construction workers and engineers will also help to build the tanks in Guatemala.

“As an engineer, I’m looking forward to working with some of the professionals to see their building techniques,” said Megan Weber, a second-year chemical engineering student.

One of the main challenges the group faces is communicating to the Guatemalan people that the tanks must be made in the way that has been approved. For example, the people in the communities where they are building like adding more water to the cement which causes it to be weaker, Antich said.

The club stays in communication with the community to follow how the tanks are being maintained, he added.

When the volunteers leave the country, Engineers Without Borders will provide the community with tools for maintaining the new tanks.

They plan to give residents an instruction manual so they can make repairs or build additional tanks on their own, Lanthier said.

Lanthier said he is interested to see how tanks his teams previously built while in Guatemala are holding up.

“Not only do you get to experience a different culture and way of life, but it’s just really fulfilling because you get to see how the work and labor that you’ve put in here can affect someone all the way over there,” Lanthier said.