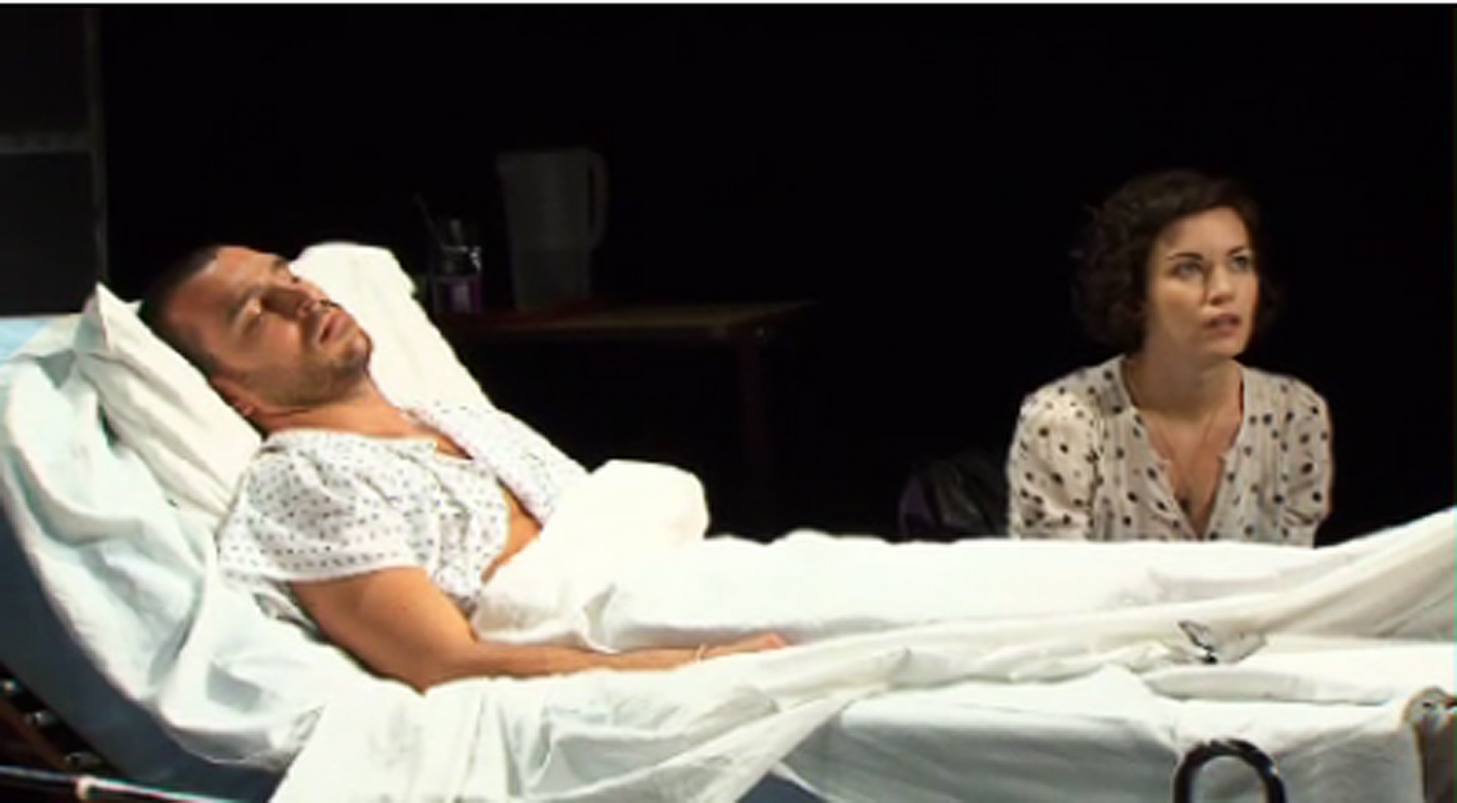

The room is still and oddly silent as the doctor breaks the news to his patient. Heart failure. Transplant. Surgery. Although the two exchange words, there is an expanding distance between their thoughts and emotions as the patient feels the world spinning beyond his control.

Currently, the field of relational medicine is bringing an empathetic approach to these crucial interactions between patient and health professional. One of these techniques is to use theater performances, and for the next three nights starting tonight, the Emotion Theater Project will present two plays that draw on the relationships between patients and their physicians.

According to Dr. Mario Deng, UCLA’s medical director of heart transplantation and founder of Relational Medicine Theory, a big factor in a doctor’s ability to empower a patient rests in emotional guidance and the patient’s free will to make decisions for his own treatment.

“It’s not just an open narrative but the emotional exchange, the chemistry between people,” Deng said. “(Relational Medicine) tries to advocate that the health professionals take the patient personally (and) practice meditative listening to empower the patient in making informed decisions.”

This concept stemmed from Deng’s work with his wife, Federica Raia, assistant professor in residence at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. Raia’s work in observing the student-teacher dynamic in classroom settings is very similar to the way health professionals and patients with illnesses communicate, she said.

“If I’m working with a kid and I just teach them things, I’m not really allowing them to be in charge of their learning. The most fundamental (aspect) is inquiry. As a scientist and educator, I (need to) answer to (the student),” Raia said.

According to Raia, while many health professionals take empathy courses in order to deal with traumatic situations they will encounter over the course of their careers, the unsuccessful integration of medicine with emotion creates the persisting divide between psychological support and medical advice.

The two plays that will be presented draw from these personal stories of alienation and disempowerment throughout the process of dealing with heart failure.

One of the plays, “Waiting Room,” written by John Henry Davis and Vanda Monaco, draws from the personal experiences of a patient who felt pressure from his doctor and struggled with the ability to freely make his own decisions about how to address complications in his heart treatment.

According to Davis, he also experienced the same feelings of helplessness during his mother’s hospitalization and wanted to create a conceptual piece that recreates the situation of disempowerment.

“In the hospital, you often feel alienated. You don’t know if they’re for you or against you,” Davis said, “It’s … confusion and desperation because it’s life and death.”

“The Catherine Wheel,” the second play written by Craig Lucas, will feature a smaller cast of two women who undergo a heart transplant. The story examines the emotions that go along with this process.

At the end of the evening, audience members will have the opportunity to engage in open discussion with the actors, playwrights, doctors and even the patients on whose experiences the plays are based. Davis said that this dialogue allows the story to be an indelible experience that stays with the audience instead of being forgotten.

Avoiding the traditional theater venue, performances will take place in the Tamkin Auditorium of the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center. Deng says the decision to choose the hospital unit over a performance space such as Royce Hall will hopefully bring realism to the art.

“It’s unfair, because we didn’t find a way to integrate emotionality and the scientific understanding. … We’ve divided them,” Raia said, “(I hope) that the sense of being in the hospital will bring art and science to be one in the other.”