Courtesy of Galerie Gisela Capitain GMBH

Alina Szapocznikow’s piece “Petit Dessert I (Small Dessert I)” is part of the Kravis Collection. The Hammer Museum is currently exhibiting Szapocznikow’s work.

In some ways, the Hammer Museum’s newest exhibition looks like the poetic debris of an apocalyptic event.

Smooth, peach-colored breasts are severed and scattered throughout the room. A man, armless and legless, hunches on the ground, his mouth a jagged hole, the outline of a blindfold seared across his eyes. On the other side of the wall, flowers spout innocently from hollowed-out heads.

This scene is the United States’ first taste of Polish sculptor and draftsman Alina Szapocznikow, who achieved immense popularity in Poland during her short life, but who was mostly ignored by the art world until recently. The retrospective, “Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone 1955-1972,” includes about 60 sculptures and 50 works on paper, created during the last two decades of the artist’s life.

The introductory scene may be disturbing. Yet its bleakness, perhaps derived from Szapocznikow’s experiences during the Holocaust, shapes an artistic vision in which horror and beauty coexist.

“I think there’s a very (unusual) combination (in her work) that is at once sexual, political, subtle and brutal,” said Allegra Pesenti, Hammer curator and organizer of the exhibition. “There are many sides to her work that incorporate very sensual beauty, but also extreme trauma.”

Born to a Jewish family in 1926, Szapocznikow survived internment in concentration camps with her mother. After the war, she studied in Prague, and moved between Paris and Warsaw. She began to receive acclaim for her work in Warsaw. In 1969, Szapocznikow was diagnosed with breast cancer, which led to a period of intense creativity, but also to her death four years later at the age of 47.

Though Szapocznikow’s style evades easy categorization, Pesenti described the artist as a cross between pop art, surrealism and nouveau realism. Much of her work deals with the ephemerality of the body, but it wasn’t until 1962, after making a severed cast of her own leg, that Szapocznikow turned her attention to her own body as the principal matrix of her art, Pesenti said.

She manipulated these casts into fantastic forms that straddled the line between life-like and corpse-like. She sometimes attempted to make the results functional. “Illuminated Lips” is a collection of colorful polyester resin lamps cast from the artist’s chin and lips. Because the lamps are covered in heat-sensitive latex, the preparators used timers to control how long the lamps are lit to prevent damage, said Jennifer Garpner, senior associate registrar at the Hammer.

Later, Szapocznikow turned increasingly toward the subject of death. “Alina’s Funeral” is made of portraits of family and friends, wrapped up with the artist’s personal belongings and sealed in a veneer of polyester resin. The giant piece hangs ominously on the wall as the artist’s confrontation with her own mortality.

In “Tumors Personified,” rock-like chunks of polyester resin and fiberglass lie on a bed of gravel, with carvings of Szapocznikow’s face peeking out from their rough surfaces.

She also used friends and family as subjects. A cast of her own son’s naked body is mounted against a wall next to ripples of flayed flesh taken from casts of her acquaintances. Some of her pieces take on alien dimensions. In Szapocznikow’s photosculpture series “Fotorzezby,” gobs of gum dangle off ledges, barely resisting gravity.

Early in her career, Szapocznikow used traditional materials such as bronze, plaster and marble, but later started experimenting with polyester resin and polyurethane foam. Both materials were very flexible, but they were also highly toxic and may have contributed to her death, Pesenti said.

With this being the first U.S. survey of Szapocznikow’s work, the execution of the exhibition took careful planning and coordination. Because a piece could not be moved once it was installed, prep crews had to work quickly to translate a 2-D image of the gallery map to a 3-D reality for visitors to experience in their walk-through, said Franky Kong, senior preparator at the Hammer.

Much of this planning is invisible as one navigates the gallery. Szapocznikow pieces bear a tension between the beauty of the human form and the sense of discomfort produced by its distortion. Growth-like protrusions and emaciated, amputated figures contrast with the delicate rendering of the smooth skin, full lips and feminine curves.

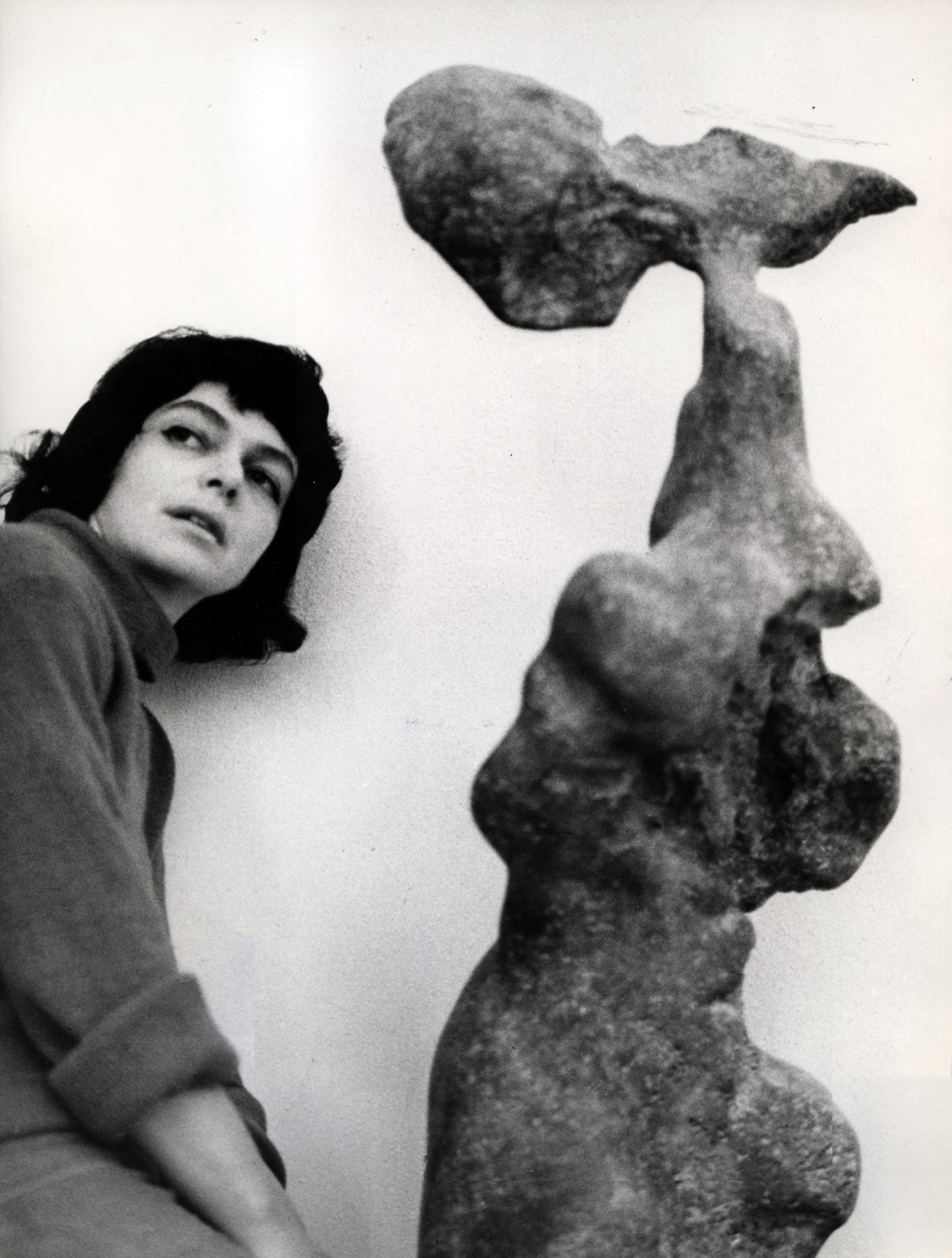

A few snapshots of the artist crop up throughout the gallery, revealing a dark-haired, dark-eyed woman with anything from an impish smile to a pensive glance on her youthful face. A silence hugs and haunts the works she created in the final years of her life.

In 1972, just a year before her passing, Szapocznikow wrote of her conviction “that of all of the manifestations of the ephemeral, the human body is the most vulnerable, the only source of all joy, all suffering, and all truth.”