Correction: The original version of this article contained an error. The song “Thinking of You” ends with an actual recording of a voice mail message from Jenny.

![]()

![]()

Perennial adolescence is perhaps pop punk’s favorite subject matter. From growing pains to always being at odds with the adult world, it thrives on the feeling that “no one else understands us.”

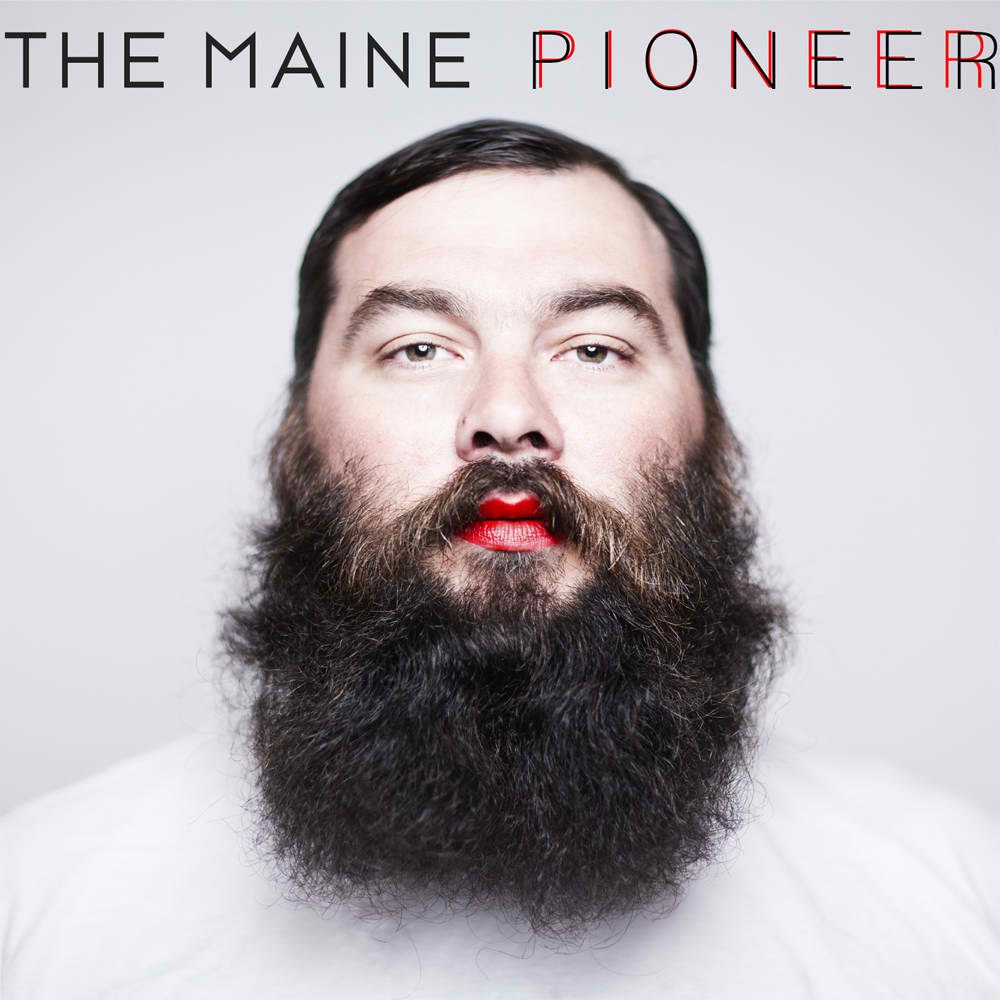

Pop punk group The Maine’s third album, “Pioneer” is its “growing up” album, and it pioneers a little. The band attempts to cross over into adult territory, trading in proto-Bieber haircuts and Vans slip-ons for20-something updo’s and worn leather boots. Sadly, its new kicks are a little too big.

What lies between “Pioneer” and maturity is The Maine’s unwillingness to stray away from or synthesize the genre’s conventions into something new and exciting. Much of the album’s sound is unimaginative, such as the overplayed riffs and bass lines of “Like We Did (Windows Down)” and “When I’m at Home,” though some unusual stylistic changes make their way into the more rock-influenced “Misery” and with the addition of slightly bluesy guitars in “Waiting for My Sun to Shine.”

In “My Heroine,” lead singer John O’Callaghan tries to turn his voice into a dirty croon, edged with insinuations and innuendos but ends up sounding like a lame Nickelback throwback.

He sings to an imaginary femme fatale, “You’re my heroine, but you’re suicide / If I let you in, you’ll crawl inside,” clearly pleased with the way “heroine” and “heroin” are homophones. After all, there’s nothing more clever or original than comparing a lover to a drug.

There is a girl involved somewhere in all of this, of course. Her name is Jenny, and she gets a song named after her that has lines like, “Before you go I want you to know I’m trying trying to be a better man” and “Just dry your eyes and take my hand.”

The chorus ends with a tepid rhyme that probably won’t impress Jenny: “Without you, there is no me / Jenny.”

While Jenny might seem like a symbolic character in “Pioneer,” it turns out she is real ““ “Thinking of You” ends with an actual recording of her voice mail message.

Even more surprisingly, Jenny turns out to be O’Callaghan’s mom, which puts a different, sweet twist on the whole track.

In “Time,” aptly named after that bandit of youth, O’Callaghan sings, “I need some time to figure out / Time to figure out / Time to figure this thing out,” as though stalling his passage into adulthood.

“Waiting for My Sun to Shine” gets gimmicky with more than four minutes of total silence in the middle of the song, as though he is actually waiting for his sun to start shining.

What’s confusing is the album’s simultaneous effort to wade through nougat-like nostalgia (“So let’s run free and carry on / Like we did when we were young”) and to tackle distinctly Western themes like slinging back whiskey, talking to the devil and being abandoned on the open road (“I’m just one pack of smokes from broke!” O’Callaghan sings over and over for two full minutes in “Waiting for My Sun to Shine” as the music gradually swells).

Dedicated fans will probably find much to love ““ a proliferation of sing-alongs, simple harmonies, one-liners and quite a bit of melodic variety.

But unless listeners have a serious taste for pop punk, the hour required to listen to the album in its entirety could be better spent doing something else.

Certainly, The Maine’s overall sound is more developed, but it lacks the stylistic or lyrical cohesion to really sell its newfound growth.

Any hints in the song writing that the band is moving away from its juvenile past sound recycled.

“Pioneer” feels like a group of boys playing dress up as cowboys. By the time the members are done with their game, they might look around and realize that not only have they outgrown their costumes, but also that they’ve been adults all along.

““ Lenika Cruz

Email Cruz at

lcruz@media.ucla.edu.