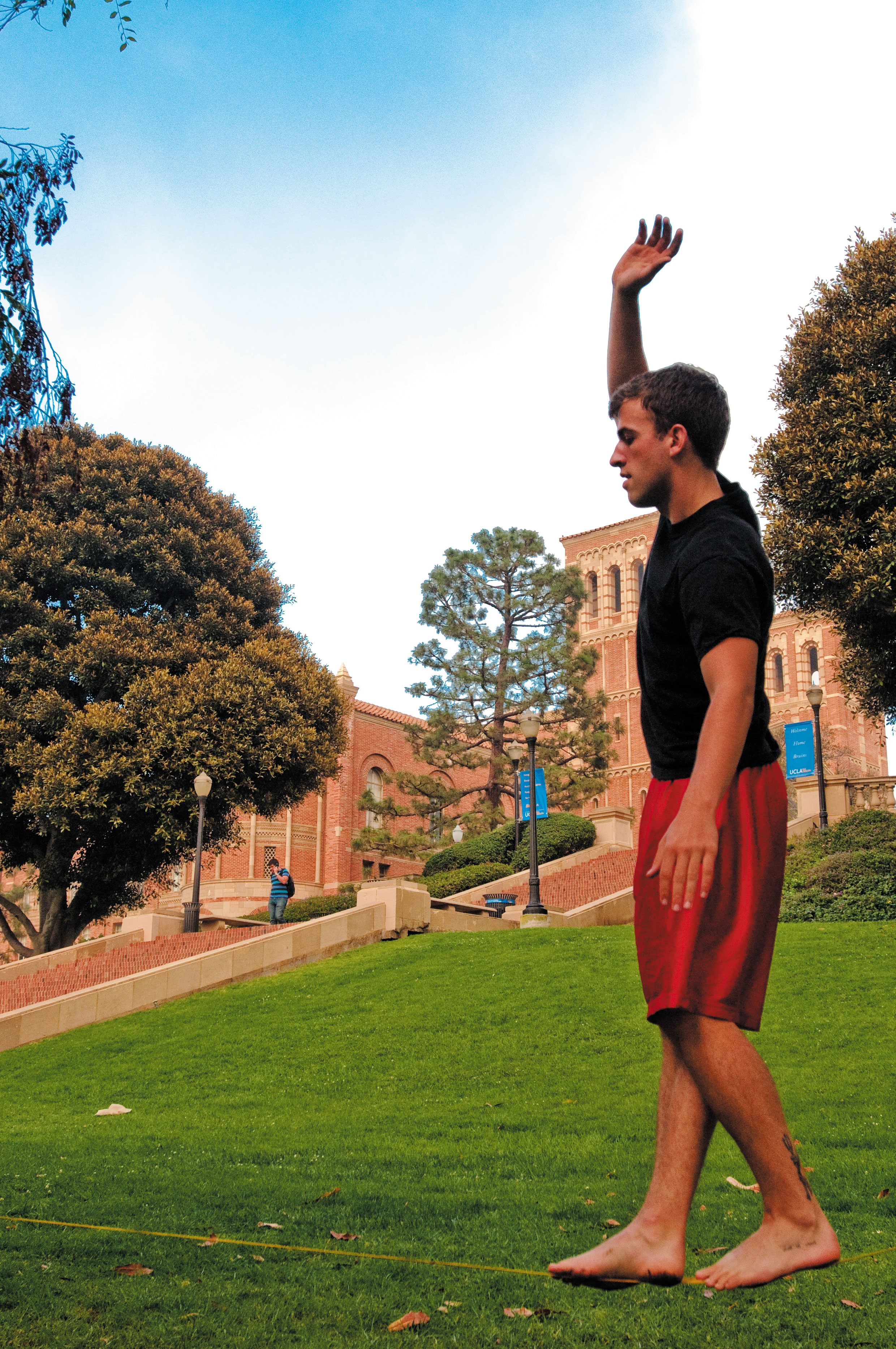

It is a common sight on the grass by Janss Steps: A student focuses intently as he walks, suspended in midair, between two trees.

Placing one foot carefully in front of the other, he jumps and spins his way down the impossibly thin and dangerously wobbly slackline. Onlookers gather, their faces a mix of intrigue and confusion at the confident acrobat before them.

Ben Steeper is one of those acrobats, and he thinks everyone else should be too.

“If we see people looking, we’ll ask them if they want to try,” said the fourth-year cognitive science student. “Usually they do, and they’re just timid about it. People need to start thinking, “˜I can learn this,’ because everybody can.”

That complete confidence is essential for success in a sport that entails balancing on a one- or two-inch wide line for distances that can span up to 80 feet. It is a feat that is impressive in its simplicity, and enthusiasts insist that it’s easier to learn than it seems.

“No one can do it the first time they try,” said Hannah Aldern, a second-year geology student who is a frequent participant in the Janss Steps group. “Everyone looks like they’re going to fall off and die their first time on the line. But you just keep trying, and eventually you get the hang of it.”

Once the initial concept is mastered, slacklining offers an ever-expanding array of tricks to tempt more experienced performers. Several members of the group make frequent trips to Santa Monica, where they meet up with world-class performers to learn new skills ““ from balancing on their arms to performing front or back flips.

Recently, a major slacklining trend has been the incorporation of yoga, informally referred to as “slackasana,” which has participants hold traditional yoga poses like warrior or tree pose in the middle of the line.

For slackliners looking for something even more extreme, the incredibly simple setup of a line allows for a limitless variety of locations. First-year neuroscience student Alex Hurley, who came to slacklining after years of tightrope walking, says the flexibility of location for the sport is a huge part of its appeal.

“One of my friends has an 80-foot line and, once, we went across a lake,” he said. “At the very middle, we were touching the water and basically walking on water. That was cool.”

Although Hurley, who was inspired to begin tightrope walking by the famous performer Philippe Petit, has years of experience with extreme sports, he says even the relative ease of slacklining can be a challenge without sufficient concentration.

“Most of the times that I’ve fallen badly, I heard someone say something, and I looked away for a second,” he said. “It’s all about focus. And core strength. But mostly focus.”

Given the amount of attention the sport attracts, blocking out these distractions can be a challenge. But performers embrace the public aspect of their sport, noting that interactions with observers are often some of the most memorable aspects of a slacklining session.

“People either flock to it, or just give you a really weird look,” Hurley said. “One time, these people asked if they could watch and then they gave me money afterwards.”

But for most slackliners, these tangible rewards don’t compare to the unique sense of community that participation in such an offbeat sport brings.

Often, they say, a person is hooked after their first attempt, and the loosely organized group gladly gains another member.

“A lot of these people don’t really have anything else in common ““ they met through slacklining,” Aldern said. “So it definitely creates a community. It just brings a lot of random, cool people together.”