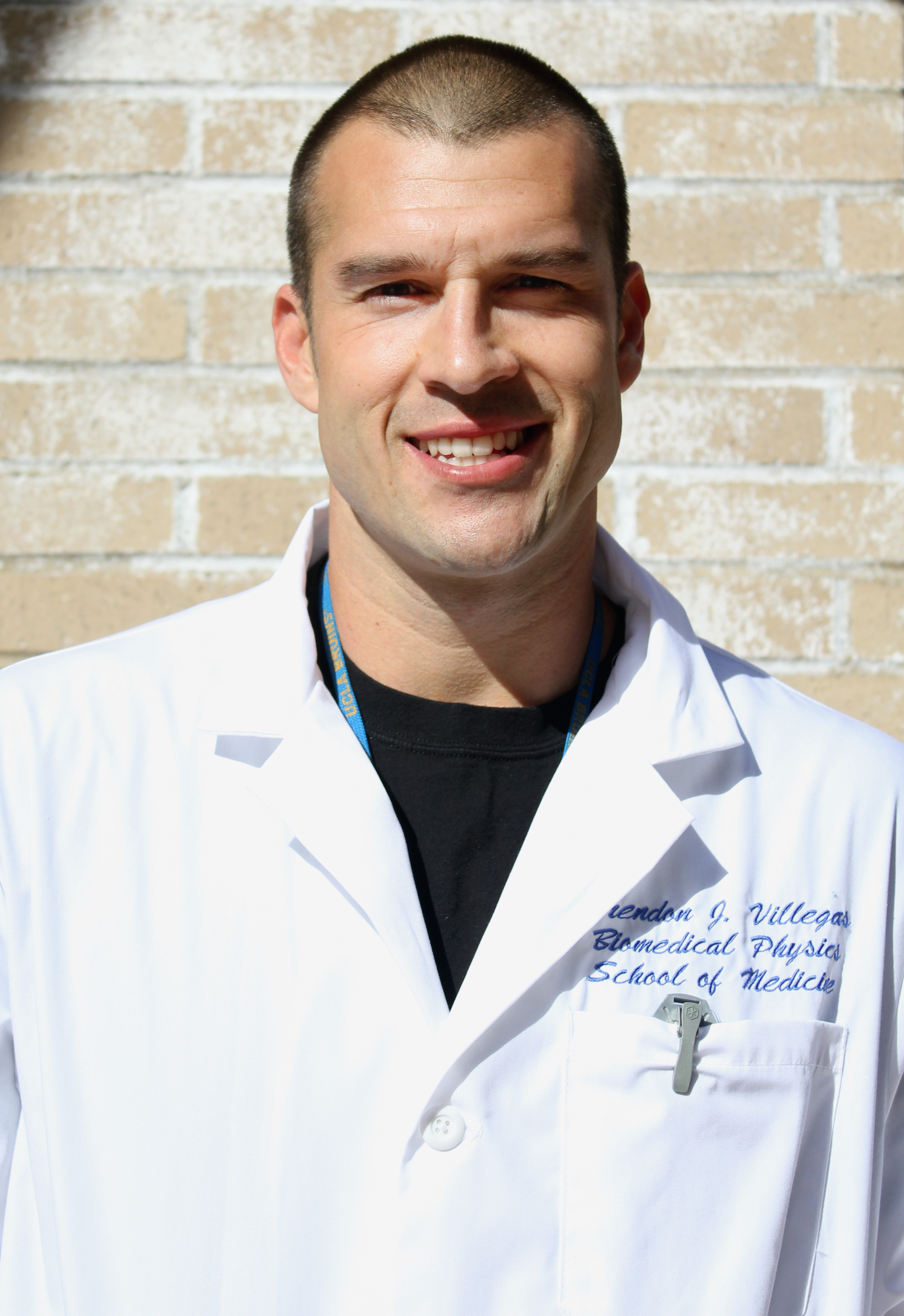

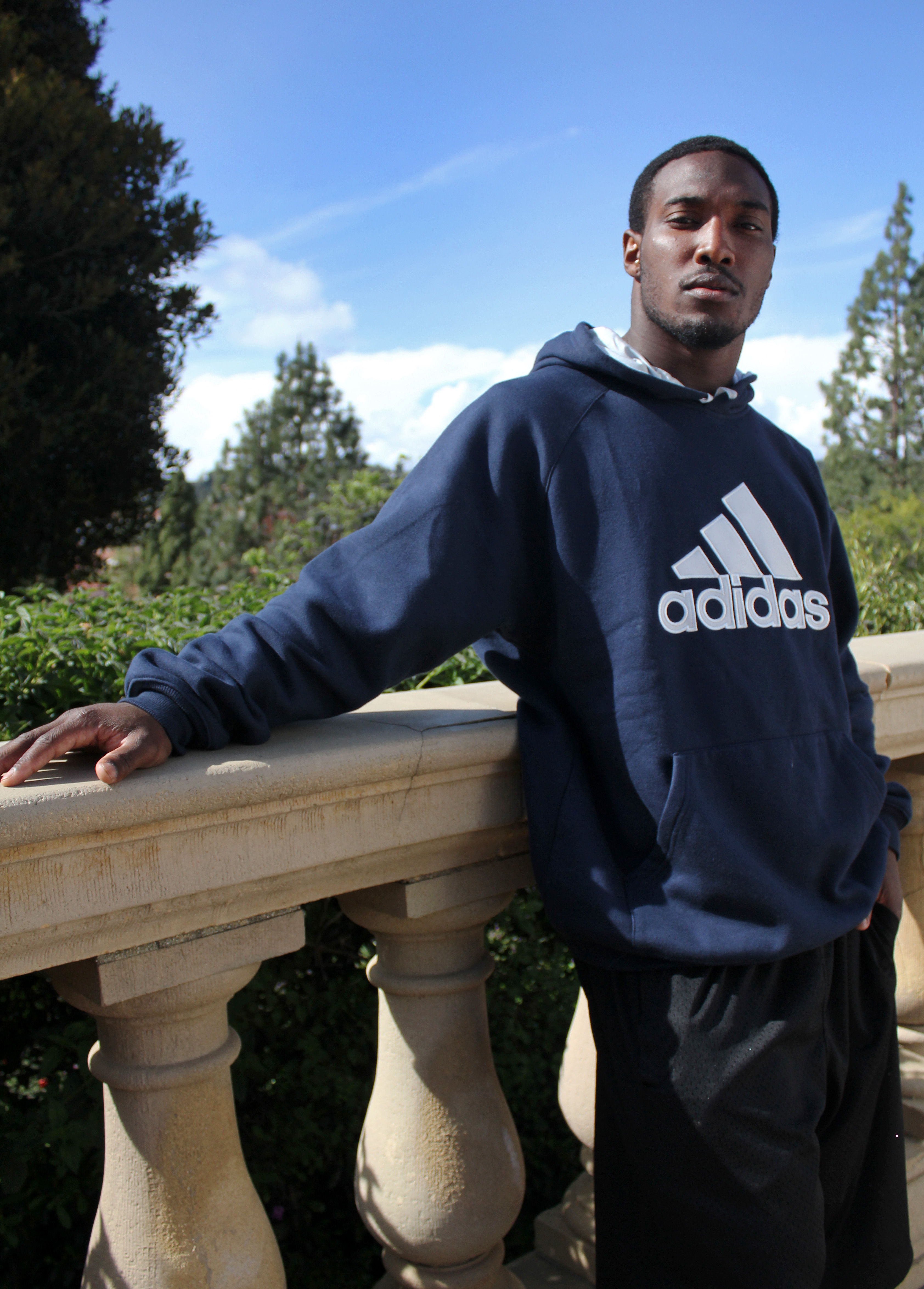

Before Brendon Villegas, graduate student (above), began his stint at the School of Medicine, he gained notoriety at different building, the Big Brother House (below). While Johnathan Franklin (below), a third-year political science student, relished his tenure as reality TV cast member, David Applebaum (bottom) found little to like about his, especially when the show was different than what it was purported to be.

Reality TV 4/15/11

As veterans of reality television will tell you, editing is a tricky thing.

In an industry where manipulation is a rule rather than an exception, the process of providing an audience with only a portion of the story is a practice that many reality detractors use to decry the genre.

But beyond the quick cuts and the “CENSORED” bars, the out-of-context confessionals and the misleading B-roll footage is a truth that often goes unnoticed: The reality begins once the broadcasts end.

Johnathan Franklin, a third-year political science student, has played his way into living rooms all over the country as the starting running back on the UCLA football team.

But he remembers a time in the not-so-distant past when he got noticed for playing a slightly different role as a cast member on the BET reality show “Baldwin Hills,” a program that followed young adults in the titular L.A. community.

“I had people follow me around at the mall. They would jump around, almost cry when they saw me,” Franklin said.

But there was a greater, more practical benefit to being on the show. A year after the BET broadcasts were done, Franklin was busy playing his way into the starting lineup on the UCLA football team.

The cameras and interviews that seemed so artificial for a college freshman on a reality show slowly became more frequent for someone trying to solidify the starting running back spot on a nationally recognized football program.

The many people who still know Franklin as “Johnathan from “˜Baldwin Hills'” have helped him find his own reality.

“The show opened my eyes to Los Angeles,” he said. “A lot of people care about status. It showed me what type of friends to pick.”

When Brendon Villegas, a doctoral student in biomedical physics, was on Season 12 of CBS’ “Big Brother,” he didn’t have the opportunity to be selective with friends.

Villegas spent nearly two months in a house with just a dozen other house guests and a camera crew, an experience that has helped him in his post-show studies and interactions.

“I’m not a confrontational person, but when you’re put in extreme situations, you’re forced to deal with things before they come back to bite you,” Villegas said.

After a last-minute format change cost him the chance to be a recurring role of ABC’s “Extreme Makeover: Home Edition,” David Applebaum, a UCLA architecture alumnus, was urged to pitch some ideas for a show of his own.

He found that, despite the fact that the genre has only existed for a decade, reality television’s success has developed its own narrow reality among television executives.

“They either want the exact same thing that they know works or something very different. They don’t realize it until they see it,” Applebaum said.

During this process, Applebaum was offered a part in the only season of Bravo’s “Launch My Line,” a show pitting professionals outside the fashion industry against each other in a competition to create their own clothing line.

Applebaum is vehement about the experience bearing zero resemblance to any official dealings in the fashion industry, citing one particular fabric selection challenge as an apt microcosm of the entire series.

“They didn’t feed us for six-and-a-half hours, we didn’t have any of the supplies that we needed and the bathrooms were locked.

That was about putting us in a situation where we’d get frantic and drop pretense,” Applebaum said.

But often times, these shows are less about a snapshot of professionalism and more about getting the audience to take an extreme approach to the “drop pretense” directive.

Even if what’s being portrayed on screen isn’t actually reality, there are legions of Internet folk who reserve their worst venom for contestants who achieve celebrity.

“I think the same people who were carving mean nasty things finally found a platform to start typing on.

Going online, that’s the one thing they tell us not to do when you get off the show,” Villegas said.

The true nature of the shows themselves is a source for endless debate, but the responses that they garner are unsolicited, raw, uncensored feedback.

When you’re online, there’s no incentive to fake being mean.

Sometimes the mark of a great television program is its character arcs, where certain individuals display a true-to-life transition from one kind of person to another.

Whether this is visible in reality television because of a construct of overeager postproduction or in spite of it, that’s where the humanity lies.